Westchester Had Deep Connection to Underground Railroad, But Some History Shrouded in Mystery

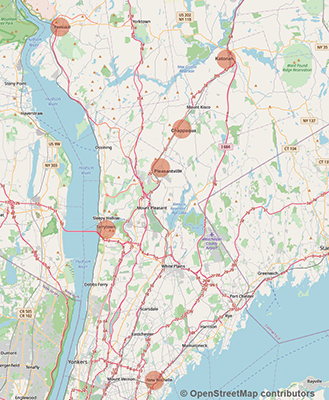

Underground Railroad in Westchester.

By Sherrie Dulworth

The Underground Railroad represents both literal and figurative historic movement. The literal movement encompassed a clandestine network of people and places helping slaves escape to freedom. Figuratively, it was part of a larger social justice movement for collective human rights.

Fugitives fled by foot, hidden in wagons or buggies, in boats or were later transported on trains. Some passed through local towns headed toward their ultimate destination of Canada.

Where are Westchester’s roots in this important piece of American history, and who were the courageous people involved?

Records are sparse.

If the escapees were found, it could lead to capture. Successful escape required discretion, with activity coordinated among a trusted circle of family and friends. In “Fleeing for Freedom: Stories of the Underground Railroad,” authors George and Willene Hendrick wrote “Hundreds of little-known people were involved in the efforts. For their own safety, most did not publicize their work freeing slaves.”

If caught, the escaped slaves risked being returned to bondage where they would likely be punished for their attempts at freedom. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 raised the stakes for those aiding slaves on the run. Penalties were as high as six months imprisonment and fines of $1,000 – more than $30,000 in today’s dollars. In addition, mob violence against abolitionists was an ongoing risk.

A code language served to protect those involved. Places of refuge were called stations, those who ran the safehouses were station masters and conductors were the people who led others to freedom.

Over a century later, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. would write, “The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.” Those who played a part in the Underground Railroad lived through their actions.

Here are several of Westchester County’s notable people and places with important roles in that historic freedom movement.

New Rochelle

One of the most active documented stops on the Underground Railroad was the New Rochelle home of Joseph Carpenter and his wife, Margaret Cornell Carpenter. Born in Scarsdale, the Quaker couple were staunch abolitionists who moved to a farm in New Rochelle in 1793. It is believed that fugitive slaves were transported by boat to Long Island Sound or over land from New York City, and then to the New Rochelle safe house. Nearby Carpenter’s Pond was named for the family.

Pleasantville

Joseph Pierce and his wife, Hannah Sutton Pierce, were Pleasantville farmers and members of the Quaker community in Chappaqua. The Pierces were related to the Carpenters through the marriage of their son, Moses, to the Carpenters’ daughter, Esther.

According to a letter later written by Moses and Esther’s son, the couple sheltered runaway slaves in their home, which was a stop between the Carpenter’s New Rochelle residence and the John Jay Homestead in Bedford about 15 miles north.

Even after the end of the Civil War, providing aid could be dangerous.

“After the Civil War when slaves were freed, there was still a lot of hostility,” said Dorothee von Huene Greenberg, professor emerita of English at Pace University.

Greenberg cites an instance when resentful neighbors drove an African American family from their home in nearby Tarrytown. The family sought shelter with the Pierces, which enraged some Pleasantville residents, who threatened to burn down the couple’s home.

In 2012, the Village of Pleasantville and Town of Mount Pleasant honored the Pierces’ courageous work with a memorial plaque installed outside the Mount Pleasant Public Library.

Chappaqua

The Religious Society of Friends, or Quakers, were the first religious organization to officially denounce slavery in the 1750s. The Quakers had a significant presence throughout Westchester, including in Harrison, Purchase, Scarsdale, New Rochelle and Chappaqua.

Although the Chappaqua Friends Meetinghouse sanctuary is not a known Underground Railroad station, some of its members, including Moses and Esther Pierce, played prominent roles in supporting abolition. The building, the oldest documented structure in New Castle, is on the National Register of Historic Places and on the African American Heritage Trail of Westchester County.

The Pierces are buried in the Chappaqua Friends Cemetery located behind the Meetinghouse.

Bedford

Founding Father John Jay was an early supporter of abolition, and his son William carried on those efforts, publicly and privately. The first judge of Westchester, William Jay inherited the Jay homestead, which was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1981. The homestead is reported to have been a safe haven used after the Pierce home in Pleasantville. The next stop was the more northerly Pawling home of David Irish, who was also related by marriage to the Pierces.

The homestead has several digital exhibits featured for Black History month, including a virtual lecture this Wednesday, Feb. 24, at 7 p.m. entitled Slavery and the Jay Family: a 7-Generation Story.

Tarrytown

The Tarrytown African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Zion Church congregation evolved from a group that was established in 1837 in New Rochelle and later in White Plains. In 1860, four of the Tarrytown members, Amanda and Henry Foster, Hiram Jimerson and the Rev. Jacob Thomas, formed a local congregation and founded the Foster Memorial AME Zion Church.

The nearby Dutch Reformed and Methodist congregations helped fund construction of the red brick building. For five years before its completion in 1865, the congregation met in the Fosters’ Tarrytown confectionary store and other businesses, while members of the church aided escaping slaves by providing food and shelter.

The Foster Memorial AME Zion Church is on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places and the African American Heritage Trail of Westchester County.

Peekskill

Along the banks of the Hudson River, Peekskill hosted several Underground Railroad stations. From the river, runaways could follow MacGregory Brook for access to nearby stations.

Hawley Green and his wife, Harriet, sheltered freedom-seekers in their Peekskill home, which reportedly had a secret stairway and hidden room. Green, a barber and free Black man, later sold the house to William Sands, a Quaker abolitionist. The house is a short distance from another asylum, the renowned Park Street AME Zion Church.

Park Street AME Zion’s parishioners included abolitionist leaders Harriett Tubman, Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass. This Wednesday at 7 p.m. the church will host an online event, Celebration of the Life & Legacy of Harriet Tubman – Peekskill Freedom Movement.

In celebration of Black History Month, a 2,400-pound bronze sculpture is on special exhibit in Peekskill through Feb. 28. Entitled Harriet Tubman: The Journey to Freedom, the artwork depicts the abolitionist leading an enslaved young girl to freedom. Created by the sculptor, Wesley Wofford, the statue is located on the corner of Central Avenue and Division Street and is sponsored by Peekskill’s Business Improvement District.

Was Your House Used as Part of the Underground Railroad?

Most of the activity of the Underground Railroad was covert, and the role of particular people and places remains a mystery and open to speculation. Without documentation, it is difficult to assess whether or not a private home was an Underground Railroad station.

Barbara Davis, co-director of the Westchester County Historical Society, said “Westchester is blessed with many 18th century houses.” According to Davis and co-director, Susanne Pandich, in the course of researching whether a home may have been used in the Underground Railroad, people can follow these steps or ask the following questions:

- Look at original deeds. When was the house constructed?

- Who were the past owners, particularly those before and in the early years following emancipation? What was their religious or known political affiliations?

- Physical structures and evidence. According to Davis, information needs to be taken in context. A hidden door, room or tunnel may – or may not – be significant but should be viewed in light of the overall picture.

To learn more, the public is welcome to attend a virtual event, “How to Research Your Westchester House,” hosted by the Westchester Historical Society on May 6 at 3 p.m.

Examiner Media – Keeping you informed with professionally-reported local news, features, and sports coverage.