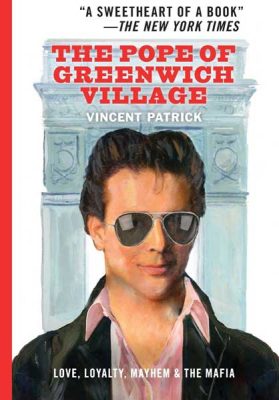

‘Village’ People, From the Late, Great Vincent Patrick

Review An assessment or critique of a service, product, or creative endeavor such as art, literature or a performance.

I was sad to see an obituary for author Vincent Patrick in the New York Times last month. Years ago, before I moved to Westchester, Patrick and I lived in the same building in Manhattan. I can’t say we were pals, but he would smoke a cigar outside the building, and we eventually got to talking–about baseball, and about writing.

I was sad to see an obituary for author Vincent Patrick in the New York Times last month. Years ago, before I moved to Westchester, Patrick and I lived in the same building in Manhattan. I can’t say we were pals, but he would smoke a cigar outside the building, and we eventually got to talking–about baseball, and about writing.

Lively convos.

I liked the guy and always planned to read his novel, The Pope of Greenwich Village, but never quite got around to it.

I picked it up after seeing his obit. He poses with a giant dog for his author photo on the back cover, and I’m pretty sure he’s in front of Pete’s Tavern on Irving Place, not far from our old Gramercy apartment, and where I started my bachelor party.

The Pope of Greenwich Village is the story of a couple half-shady guys in Manhattan. Cousins Charlie and Paulie work in restaurants, Charlie as a manager and Paulie a waiter, and also keep their eyes open for heists and scams should the opportunity present itself. Charlie grew up on Carmine Street in Greenwich Village, but the book, despite the title, rarely ventures downtown. About the title, Charlie spoke of inventing his own religion as a kid, and getting two neighborhood kids to attend masses in his building’s basement.

“They refused to make me pope of the whole world–they tried to say I was only the pope of Greenwich Village,” he says.

It’s not a title he ends up living up to.

Paulie learns of a job–a safe used by a trucking company that may hold $50,000 or so. They pull in a safecracker–a guy named Barney who fixes clocks up in the Bronx–and plot the theft.

As the trio is on site, breaking into the safe late at night, an off-duty police officer sees them sneaking around the otherwise empty building. He enters, confronts them, and it does not end well for the cop.

The cop, named Bunky, was hardly a good Samaritan; he was there to pick up the cash and deliver it to a mobster, with a taste for himself.

The safe ends up holding way more than the thieves envisioned. At first, they think they are set for life, or at least the next few years. Then they realize they’ve stolen from a ruthless mobster, Bedbug Eddie, and may not make it to the end of the month.

It’s a fun story. The book was published in 1979, and Patrick captures a New York City you simply do not see anymore–filthy and violent and profane, everyone looking over their shoulder.

As is the case with most any novel published four decades ago, aspects of The Pope of Greenwich Village do not hold up here in 2023. Charlie and Paulie do not speak well of Blacks, Hispanics and homosexuals. Charlie’s girlfriend Diane blasts him for using the n-word. “Is it so hard to say ‘black’? I’ve asked you a dozen times,” she says.

In his Afterword, Patrick said he contemplated toning down “the coarseness and rawness” of the dialogue when the book was republished in 2014, and decided not to. He quoted author John O’Hara in his explanation: “I want to record the way people talked and thought and felt, and to do it with complete variety and honesty.”

Paulie is a dolt, but Charlie is somewhat likable. Having said that, the book lacks characters the reader really wants to root for. Both broke, the cousins contemplate stealing the thousands Barney has left for his retarded son before skipping out of town with Bedbug Eddie looking for him. Charlie likens it to stealing quarters out of that March of Dimes display you remember from the days of yore, next to the cash register at the diner.

Paulie says, “You stand there pulling quarters off the cord with the little kid in the wheelchair looking up at you, you worry that somebody in your family might get polio. It don’t happen. And I’ll tell you, Charlie, nothing’s going to happen if we keep the retard’s money.”

Paulie’s thumb was cut off by Bedbug Eddie–a pound of flesh, indeed–and the mobster is on the hunt for Charlie.

The book has a 3.92 out of 5 on GoodReads. The New York Times Book Review said the author “mines territory rarely encountered in fiction and, in the vernacular of his tough streetwise characters, delivers a sweetheart of a book.”

Playboy called it “impossible to put down.”

The movie came out in 1984, and Vincent Patrick wrote the screenplay. Mickey Rourke played Charlie and Eric Roberts played Paulie. Daryl Hannah was Diane, and Burt Young, another New Yorker who died last month, portrayed Bedbug Eddie. (Eddie’s full name is Eddie Grant, a peculiar name for a mobster, and a name that might just get “Electric Avenue” stuck in your head.)

Patrick was 44 when The Pope of Greenwich Village came out. He also wrote the novel Family Business, which inspired a 1989 crime film with a star-studded cast that included Sean Connery, Dustin Hoffman and Matthew Broderick.

His NY Times obituary reads, “The son of a Bronx pool-hall owner and numbers runner, Mr. Patrick was raised in a milieu sprinkled with the grifters, hustlers and mobsters who would eventually become characters in his novels.”

Vincent, I’m sorry it took me so darn long to read The Pope of Greenwich Village. I enjoyed it. I also enjoyed our chats in front of the building.

Rest in peace.

Freelance journalist Michael Malone lives in Hawthorne with his wife and two children.

Corrections:

Sourcing & Methodology Statement:

References:

Examiner Media – Keeping you informed with professionally-reported local news, features, and sports coverage.