Tracking and Understanding the Cycles of the Moon in Our Skies

Opinion Advocates for ideas and draws conclusions based on the author/producer’s interpretation of facts and data.

By Scott Levine

By Scott Levine

A fun, or just mildly interesting, piece of information that those of us who watch the skies can keep track of are the moon’s phases and see how they fall relative to our calendars each month.

Our word month comes from an old word, moonth, which is the amount of time it takes for our moon to go through one cycle.

Astronomers measure months a few ways, but it’s easiest and most practical for people like you and me to follow the lunation – the amount of time the moon takes to go from one phase back to that same phase again. It’s usually measured from one new moon to the next, and takes about 29.5 days.

Many calendars, Islam’s Hijri calendar among them, are strictly tied to the lunar cycle. The months on the Gregorian calendar, the one we use, are mostly either 30 or 31 days, a little longer than a lunation. Some quick math tells us that there about 13 lunations a year, but only 12 months. This means as each of our months pass, the moon’s phases float a little toward the calendar month’s start.

This week, as June starts, we’ll see the bright and beautiful moon for most of the night, about two days before it’s full. It’ll be in the constellation Libra, the scales, near the flamboyantly named stars Zubenelgenubi and Zubeneschamali.

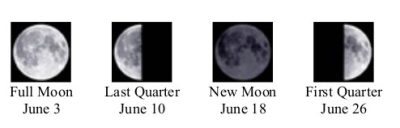

On June 3, the now-full moon will appear close to the bright star Antares. To get an idea of how these small changes in the night sky add up, this time last year the moon was a thin, waxing crescent, just a day or two after it was new. A year from now, it’ll be deep into its waning phases, on the long, dark overnight shift. This July’s full moon is on the second, and then August will have two: on the 1st and also on the 30th. A month’s second full moon is often called a blue moon.

But Earth isn’t the only planet with moons. What would months be like on some other worlds?

The larger of Mars’s two tiny moons, Phobos, orbits so close to the planet’s surface that it orbits faster than Mars spins. It makes it all the way around in about eight of Earth’s hours. If we are watching the skies from the red dust on Mars, we’d see Phobos rise in the west, cut across the sky and then set in the east. Then the whole thing would repeat four hours later. Mars’s days, like Earth’s, are about 24 hours long, so there’d be three months every Martian day (which, by the way, we call a sol).

At the other end of the solar system, the tiny moon Neso, orbits more than 30 million miles from Neptune, which is almost as far as the planet Mercury is from the sun. At that distance, it orbits so slowly that it takes over 26 years to finish one orbit. That’s almost as long as a year on Saturn! Needless to say, it’s a long time between one full Nesos and the next.

It might not sound like much, but as we slide into summer, let’s take another chance to see how connected we all are to the night sky. Clear skies, everyone!

Scott Levine (astroscott@yahoo.com) is an astronomy writer and speaker from Croton-on-Hudson. He is also a member of Westchester Amateur Astronomers, a group dedicated to astronomy outreach in our area. For information about the club including membership, newsletters, upcoming meetings and lectures at Pace University and star parties at Ward Pound Ridge Reservation, visit www.westchesterastronomers.org.