Standing Up Against Threats – A Tale of Two Journalism Projects

Opinion Advocates for ideas and draws conclusions based on the author/producer’s interpretation of facts and data.

‘Boss Hogg’ Wannabes Exposed by Local Newspaper in Oklahoma

When I first spotted a Tulsa TV news anchor’s tweet two weekends ago about the horrifying threats leveled against local newspaper journalists in McCurtaind County, Okla., I immediately thought of my late mentor, legendary former Newsday editor Bob Greene.

When I first spotted a Tulsa TV news anchor’s tweet two weekends ago about the horrifying threats leveled against local newspaper journalists in McCurtaind County, Okla., I immediately thought of my late mentor, legendary former Newsday editor Bob Greene.

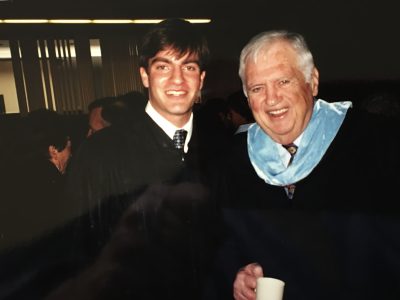

As a student of Greene’s at Hofstra on Long Island in the late 1990s, he taught his cubs (that’s what the big bear of a man called us) about the sense of mission we should carry with us to our work, whether covering national news, a big city beat or routine small-town happenings.

The most inspiring example from Greene’s illustrious career was his leadership role in orchestrating what became known as the Arizona Project.

I will always remember how awestruck I was when Professor Greene first told us about the project; he rallied journalists from across the country to descend on Arizona and continue the investigative work of Don Bolles, a newspaper reporter murdered by a car bomb in June 1976.

Some rotten people didn’t like Bolles’ exceptional work, probing organized crime and corrupt land deals. Greene’s intent in coordinating the Arizona Project was to illustrate in deed how investigative reporters would not be cowed by threats or acts of violence.

In fact, Greene was sending the very intentional message that the murder of a journalist would only embolden reporter colleagues to continue the work in even grander fashion.

While I can’t speak authoritatively to the day-to-day editorial chops of the McCurtain Gazette-News, good or bad, they’ve certainly displayed world-class guts amid a chilling local landscape.

‘Killing, Burying Gazette Reporters’

A broader storyline in our country and across the world of powerful people seeking to silence the press echoes far beyond McCurtain County.

The arrest last month and ongoing detainment of Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich by Russian authorities is just one recent and prominent example of the growing threat national and international journalists face in particular – 363 reporters were in prison around the world as of December, more than at any point in the past three decades, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

As for the small McCurtain publication, the print newspaper published an article (and released a corresponding audio recording) where local leaders, as the headline put it, “discuss killing, burying Gazette reporters.”

But that’s not all from these classy county officials, who the state’s Republican Gov. Kevin Stitt and many others have called on to resign. (One county commissioner stepped down while the others still resist, as of my Apr. 24 deadline.)

The audio captured McCurtain County officials harkening back to what they apparently consider the good old days, when people could be lynched because of their skin tone.

And there’s more!

The recording also revealed their grisly, heartless talk about a burn victim.

The Gazette-News’ Apr. 15-16 weekend edition’s front page chronicled the whole sordid affair.

‘Intimidation, Ridicule and Harassment’

I called the Gazette newsroom last week, seeking to interview Publisher Bruce Willingham, but received a reply from an attorney with the Kilpatrick Townsend law firm instead.

An e-mail from the lawyer explained how the publishing family has lived in the county for nearly 120 years. They’ve run the Gazette-News for more than four decades.

“For nearly a year, they have suffered intimidation, ridicule and harassment based solely on their efforts to report the news for McCurtain County,” said the statement from Christin Jones, an attorney for the McCurtain Gazette-News and the Willinghams. “They love their county and the people in it dearly.”

(Authorities laughably tried to discredit the audio, calling it “altered” in an Apr. 17 Facebook post.)

It’s critical to understand the context behind the menacing comments from the county officials.

Chris Willingham, Bruce’s son, had been exposing alleged corruption and general sliminess inside the McCurtain County Sheriff’s Department in a series of investigative stories.

In fact, on the same day the recording was made, on Mar. 6, Willingham filed a defamation lawsuit against the Sheriff’s Department, the Board of County Commissioners, Sheriff Kevin Clardy and county investigator Alicia Manning.

A voicemail message I left with the Sheriff’s Department last week was not returned.

Picture This

I was provided with a copy of the lawsuit, which details the nature of Chris Willingham’s reporting and its jaw-dropping revelations.

Details inside the lawsuit and within the paper’s coverage about the Sheriff’s Department paint a deeply disturbing picture of tainted homicide evidence, illicit sexual relationships, nepotism, attempted extortion and other serious offenses.

“Journalists and reporters may be victims of threats and harassment, yet the press provides a crucial service necessary for any democracy to function: accountability for public authorities,” the lawsuit declares.

For anyone who might have missed last week’s national coverage of the vile McCurtain gang’s gathering, let’s quickly review just a few of their greatest hits from Mar. 6. Bruce Willingham secretly recorded the official board session because he suspected the officials were bucking opening meetings law.

This motley crew of Boss Hogg, Hazzard County wannabes featured no members of the Chris Willingham Fan Club. Chris had published an eight-part investigative series about the sheriff’s office, in 2021 and 2022.

County Commissioner Mark Jennings: “I know where two big deep holes are here if you ever need them.”

Sheriff Kevin Clardy: “I’ve got an excavator.”

Jennings: “Well, these are already pre-dug.”

Ah, how charming.

Now, here’s a violently racist tangent from the recording, not referring to the Willinghams.

Jennings: “If this was back in the day when Alan Marston would take a damned Black guy and whoop their ass and throw them in the cell, I would run for f**** sheriff.”

Sheriff Clardy: “Yeah. Well, It’s not like that no more.”

Jennings: “I know. Take them down to Mud Creek and hang them up with a damn rope. But you can’t do that anymore. They got more rights than we got.”

And, last but not least in our sampler, here’s a little taste of their casual talk about murder-for-hire.

Jennings: “I’ve known, I’ve known two or three hit men, they’re very quiet guys.”

Manning: “Yeah?”

Jennings: “And would cut no f**** mercy.”

I’ll just let you poke around online to read about barbecuing body parts and an unrelated fire victim.

Hold the Applause

Reverberations from the unsettling and violent talk in McCurtain County unfurl as many people around the country applaud the weakening of the American free press.

People sometimes make the mistake of lumping “the media” into one big soup, failing to distinguish between, say, a phony cable TV news celebrity and a ratings-hungry radio show personality and an overworked newspaper beat reporter pounding the local pavement.

But no matter your ideological inclination, if you’re in favor of transparent, honest government, the haranguing and subsequent dilution of local media produces bad outcomes for the general public.

To dig deeper on the broader subject, I contacted Oklahoma journalist Randy Krehbiel, who has been with the Tulsa World newspaper for more than four decades.

I connected with him last week after reading his reports on the McCurtain County scandal.

One subject I was curious about was whether Krehbiel has observed any related (or even tangentially related) changes on the fundamentals of reporting and civic affairs in his many years covering news in the state.

“As somebody who’s been at this newspaper since 1979, one of the most discouraging trends is how many people don’t read,” Krehbiel said. “This is especially true of elected officials. We have high-ranking elected officials who clearly don’t read anything, whether in print or online.”

To me, the newspaper industry’s struggles and the demonization of reporters is of a piece with the type of diminished standards elected officials even set for themselves when it comes to staying genuinely informed with credible sources. Too many appear to be stuck inside partisan social media information silos. Some value “likes” more than learning.

While it’s purely speculative, I think it would have been far less realistic for these disgraced Oklahoma public figures to have tried to hold onto their jobs if a story like this broke in the late 20th century, if not a half-dozen years ago.

“All they know is what the people around them tell them,” Krehbiel said about some contemporary elected officials. “That seems to be pretty common nationwide. I’m told our last president was in that category.”

‘No Words’

The notion of independent journalists rallying to each other’s cause when violence or threats of violence are afoot seemed to be on the mind of Tulsa-based news anchor Erin Christy of KJRH when she started posting tidbits of reporting about the unfolding scandal.

Her Apr. 15 social media post of the print newspaper’s front page was retweeted thousands of times (including one from me) and was how I heard about the Gazette-News story before she helped the news go national with her amplification efforts.

“There is a ‘no words’ story coming out of McCurtain Co today involving county leaders discussing killing local journalists, flagrant racism & mocking a woman’s death from an arson,” her first tweet on the topic began, sharing an image of the Gazette-News’ print cover.

It’s a similar spirit that fueled the energy behind the Arizona Project almost half a century ago.

I remain amazed to this day when thinking about the level of leadership muscle Bob Greene had to flex from Long Island in order to rally reporters from all over the country to travel to Arizona and continue Bolles’ investigations.

Many of the journalists were granted leave by their newspapers but some quit their jobs or took vacation time to join the reporting posse, which became known as the Desert Rats.

“We are buying life insurance on our own reporters,” Greene was quoted as saying at the time.

If Greene were alive today, I suspect he’d place the emphasis on the fact that the release of the audio is far from the end of coverage needed on the larger story.

Just last week, Barbara Barrick, the widow of a man who was killed in March 2022 while in the custody of deputies, filed a wrongful death civil rights lawsuit against the sheriff, the McCurtain County commissioners, several deputies and others.

“The community has had division in it for quite some time, so for the Band-Aid to be ripped off and for us to be able to see under the camel’s tent, it’s amazed all of us,” attorney Mitchell Garrett, who is representing the Barrick family, said to the local press, referring to the Gazette-News’ blockbuster coverage of all the interconnected events.

And you also have to worry about the chilling effect on sensitive reporting when there’s even the specter of potential violence.

The Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ) National President Claire Regan told me her organization is “appalled that McCurtain County, Okla. officials talked about possible plans to kill two local reporters.”

“Many journalists must work with government officials every day and deserve to feel safe while doing their jobs,” Regan said. “It’s alarming when those officials show malice toward reporters who are working to keep their communities informed. The safety of all journalists is of the utmost importance.”

I wondered if my hope of an Oklahoma Project, in the spirit of Greene, was too grandiose.

“Not pie in the sky at all,” Regan replied. “Journalism orgs frequently join forces as a coalition.”

Just a couple weeks ago, she pointed out, the SPJ joined more than two dozen other journalism organizations in writing a letter to President Biden, calling on the administration to prioritize the release of Gershkovich and U.S. journalist Austin Tice, who was kidnapped in Syria more than a decade ago.

When talking to Regan, I offered to play my small part in helping with any potential effort on an Arizona Project 2.0, McCurtain County Edition, in Greene’s honor.

Whether in Arizona in 1976, or in Oklahoma in 2023, it’s imperative for journalists to form something akin to a community – at least for a news cycle or two – and collectively proclaim a commitment to the cause in the face of violent threats.

As Greene often said, the Arizona Project was about telling the world how killing journalists won’t kill the story.

Thank goodness, in McCurtain County, the Willingham family is alive and well.

“While they are thankful for the wide attention the story has received,” the family’s statement from the lawyer concluded, “they look forward to the day when they can continue to report the news and not be the news.”

Adam has worked in the local news industry for the past two decades in Westchester County and the broader Hudson Valley. Read more from Adam’s author bio here.