Pro Baseball’s First Known Black Player (No, not Jackie)

Opinion Advocates for ideas and draws conclusions based on the author/producer’s interpretation of facts and data.

Our Local Equity Fights are the Latest Chapter in an Old Story

He was a Black baseball trailblazer. Organized pro ball’s first known African-American player. A Hall of Famer who starred right here in New York, a car ride from Westchester.

And no, I’m not referring to Jackie Robinson.

Let me explain.

Last weekend I took a pilgrimage with my older daughter to Cooperstown, for our second trip together to the inimitable Baseball Hall of Fame Museum. (My sixth visit, including twice in childhood).

When we arrived at the Negro League section of the exhibit, we expected to learn about, well, Negro League Baseball.

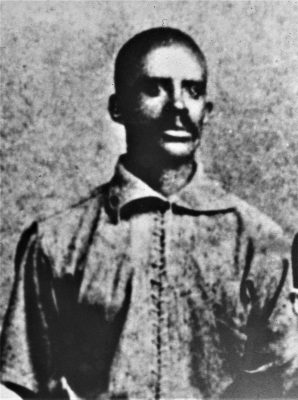

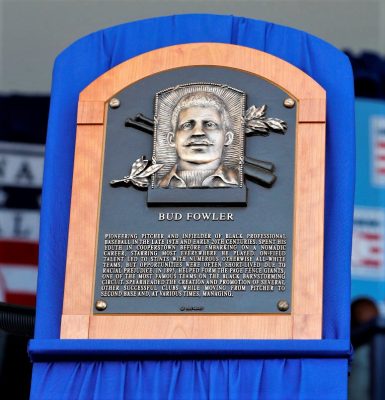

But the images on the museum’s hallowed walls that captivated us most were of Bud Fowler, the earliest known African-American player in organized, professional, mostly white baseball; Fowler was inducted posthumously to the Hall just four months ago, in July.

COLOR WARS

A Cooperstown resident himself as a boy, Fowler began his long career of playing, coaching, and promoting the game in 1878, starting as an infielder and pitcher.

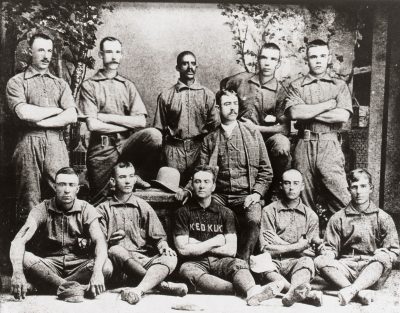

Fowler was flanked by white teammates in one of the photographs we saw, and we started to read up about the history of African-Americans in pro ball. We were most interested in this window of late 19th century time when a stricter color line had yet to emerge and firmly harden.

Needless to say, we discovered how Fowler endured nasty, persistent racism throughout his baseball life. As a matter of fact, Cap Anson, one of the game’s early greats, helped orchestrate efforts to stymie any acceptance of people of color in pro ball, Fowler and otherwise.

The race hatred propelled Fowler into a nomadic baseball life, leaping from one team to another. By 1890, Black players were effectively banned, a caption accompanying a photo of Fowler at the exhibit explained.

“My skin is against me,” Fowler later wrote, in 1895, the same year he helped found The Page Fence Giants, a famous Black barnstorming team.

“The race prejudice is so strong that my Black skin barred me,” added Fowler, whose birth name was John W. Jackson.

In examining Fowler’s life, it struck me how you can tell the story of America’s late 19th-century and early 20th-century reckoning with race through Fowler’s journey.

BACKLASH

The Civil War over, and the slaves freed, Reconstruction just ended as Fowler’s baseball career began. But the post-Reconstruction backlash to progress impacted every walk of American life, and baseball was far from immune.

Some opponents and teammates refused to play if Fowler or other people of color took the field. That led to both formal and informal aspects of the eventual ban, a result of both tacit “gentleman’s agreements” and officialdom.

In the decades that followed in the United States, an infinite volume of acts, large and small, produced various degrees of racial progress, culminating, in baseball’s case, with Jackie Robinson’s famous debut for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. (Just a half dozen years after a poverty-stricken and sickly Fowler died in 1913 in Frankfort, NY, a healthy baby named Jack Roosevelt Robinson was born in Cairo, GA.)

Amidst and after Jackie’s triumphs, in the 50s, 60s, and even the 70s, the fight was about basic civil rights. In the 80s, 90s, early 2000s, and 2010s, the battle was about pushing for progress in having the spirit of the law match the letter of the law, not to mention reforming the law itself, to address social justice.

And now, in the 2020s, as those older battles endure, there’s also an intensifying fight over equity in our culture, examining the way our diverse melting pot of a country interacts at school, at work, and throughout every walk of daily American life. It’s about understanding our complicated past, and how that past impacts our present and forecastable future.

In this era, it seems a week can’t go by where we don’t end up pulled into covering a local saga with race at the forefront, or at least within the subtext. Just as we were writing about the story of a Somers High School English teacher getting raked over the coals a couple of weeks ago for using a controversial anti-racism book in a lesson, we were also drawn into reporting out last week’s local fight involving race and flavored nicotine.

Our piece this week about the local Black community’s debate over the county legislature’s plan to ban flavored tobacco in Westchester got me thinking about the mind-boggling progress civil rights advocates have achieved over the past 150 or so years — the snap of a historical finger — and about what tactics have been used since Fowler’s day to arrive at that progress.

In fact, it also got me thinking about how much additional progress today’s and tomorrow’s activists and pioneers will more than likely realize over the next generation or two.

On Monday, different factions of Black activists debated at a public hearing whether banning flavored tobacco in Westchester was a good idea, given the popularity of menthol cigarettes in the community.

Some Black leaders believe the ban is a great way to improve public health. Others say it can lead to racially-biased enforcement with life-threatening consequences, as the late Eric Garner’s mother asserted at a White Plains press conference — her son was notoriously choked to death in 2014 by Staten Island police during an arrest for selling loose cigarettes.

BACKWARDS AND FORWARDS

Contrasting the 19th and 20th-century debate over the racial ban with a 21st-century debate over a flavored nicotine ban is not at all designed to minimize today’s battles. In fact, just the opposite. (It’s also worth emphasizing how many of the racial issues we face today feature more nakedly brutal inequities — in the areas of housing, policing, and incarcerating, to name just a few).

Yet if Fowler were here today, he’d be flabbergasted at our incredible progress, living in a country with a female Black vice president, a Black former president, two Black Supreme Court justices, and, not for nothing, Black Major League Baseball executives, Black managers, Black players, and all the rest. All that advancement has been accomplished in a historical eye blink of time, with segregated water fountains federally outlawed only 57 short years ago.

Fowler would also discover an America painfully striving to become a more perfect union, where grinding, slow, incremental progress is only achieved because people fight and fight hard for advancements large and small, whether that means an inter-community squabble over the proper solution to predatory cigarette marketing or the complicated efforts to appropriately reform policing. Good progress doesn’t and shouldn’t mean good enough.

For anyone who thinks we’re spiraling indefinitely backward, it’s worth remembering how basic physics also applies to culture and politics— for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction, whether in Fowler’s era or any other.

Just as reconstruction created a backlash, U.S. racial tensions were also stirred by the election of the first Black president in 2008, ushering in populist pushback. Then came George Floyd’s murder, and all we’ve been fighting about ever since here locally and across the country and the globe.

These spasms, while unsettling to live through, seem to be both inevitable and the precursor to more enduring, positive change. Fowler’s ascent spawns Anson’s rebukes. MLK’s dream triggers Wallace’s taunts. Palin and then Trump’s populism, followed by Floyd’s murder, ushers in constructive aspects of D.E.I. as “woke” excesses also generate simultaneous pushback — both nuanced resistance and hateful indictments.

More than six grueling decades unfolded before Fowler led to Jackie. America’s remarkable story of progress often seems to be a story of pioneers ferociously fighting across generations to gain one step, then fall two back, before their movement’s children and grandchildren leap three or four steps in front of where their predecessors started.

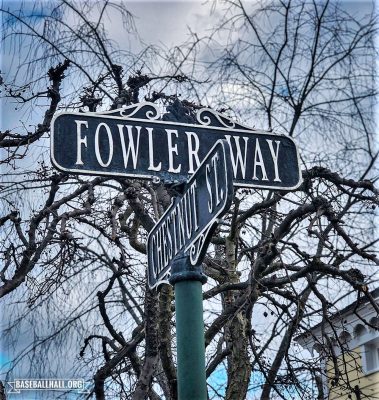

It’s encouraging to know how American history, from an institutional standpoint, is remembering these trailblazers. There’s even a Fowler Way in Fowler’s native Cooperstown.

So, with all this in mind, if you haven’t ever been to the Hall of Fame Museum, or are itching to return, do yourself a favor and make the trek to Cooperstown.

At the museum, you’ll learn how baseball’s story is the story of America’s past century-and-a-half of pain and glory. (Not to mention how you’ll also enjoy a much more light-hearted good time).

It’s a three-and-a-half-hour drive you won’t regret.

Epilogue:

It should also be quickly noted how this column, due to space constraints, neglects to capture the more complicated history of race rules in late 19th-century baseball and also fails to carefully dissect the differences between pro ball and the emerging “major leagues.”

In general, all-Black teams were barred from the majors of the 1880s, according to the Mo.-based Negro League Baseball Museum.

But individual Black players did receive opportunities to play, Museum Vice President and Curator Raymond Doswell told me.

Moses Fleetwood Walker is recognized by most historians as the first African-American in the major leagues. Complicating matters further, a Black player named William White arrived first in 1879, but he pretended to be white.

Adam has worked in the local news industry for the past two decades in Westchester County and the broader Hudson Valley. Read more from Adam’s author bio here.