Potential Progress at Optum Tri-State Complicated by Corporate Care Crisis

Opinion Advocates for ideas and draws conclusions based on the author/producer’s interpretation of facts and data.

‘IT’S BONUSES FOR BODIES’

This is the 16th installment in an investigative series, launched in December 2022, about CareMount/Optum/UnitedHealth and broader concerns about corporate medical care.

By Adam Stone

Let me start off by saying I read the letter from Optum Tri-State to patients last week about the announced improvements, and the efforts sound potentially meaningful, credible and significant, even if developing within the context of broader structural hurdles to truly fulfilling community needs.

I promise to get to that later in this piece, and shine a bright spotlight on any substantive plans to address systemic issues.

But I already had reporting prepared on a non-local aspect to Optum’s troubles, with local implications, so let me take you through that first, which doesn’t minimize any genuine internal efforts at real regional reform.

Here’s the thing: Anyone eager to better understand how the profits-over-patients culture has impacted our local healthcare here in the lower Hudson Valley needs to examine how the organization and ones like it have influenced the practice of medicine in facilities across the country.

I know this piece is a long ride to the larger point but buckle up and pretend you’re reading a few book chapters instead of a newspaper column, because all of the context matters, and interconnects.

We’ll start with one particularly relevant scene from the New England area, indicative of the ethical ramifications that come when corporations run healthcare, instead of doctors.

‘Preferably on Hospice’

On June 29, 2023, a group of about 150 to 200 physicians, physician assistants and nurses gathered for a remote meeting with Optum business leadership, for one of their regular Thursday sessions.

A regional home healthcare division had previously revealed a new internal plan for 2023, even if it was presented as business as usual for Optum-owned Landmark Health, and dressed up in obfuscated language: the group would give bonuses to medical professionals linked to end-of-life care.

Two years earlier, in February 2021, Optum purchased Landmark for a reported $3.5 billion, and the financially-geared data culture was expanding, just as it did in our region after the multinational behemoth finalized the acquisition of CareMount Medical in 2022 for what I’ve been told was in the neighborhood of $2 billion.

(Landmark provides home-based medical care for people with complex health needs.)

Medical professionals enter homes, cultivate deep relationships with patients, as well as their loved ones, and eventually might begin a constructive conversation around palliative care or possibly hospice.

At the June 29 Landmark/Optum meeting, a member of the medical team challenged leadership to plainly reaffirm the alleged bonus plan.

“So in quarter three, starting quarter three, a quarter of our bonus is based on how many hospice referrals we make, is that correct?” a medical staffer flatly asked at a remote meeting.

Initially the question from a physician assistant yielded mostly corporate-speak in reply from both an executive as well as a doctor who helps steer business operations.

But the doctor involved with business operations eventually got to the crux of the matter.

“So, of course, clinically it makes sense we’d want our patients, if they are at end of life, to die preferably on hospice, rather than dying without hospice in the hospital,” the medical executive said. “Okay. Does that make it a little bit more clear?”

‘It’s Bonuses for Bodies’

It’s critical to emphasize right here at the jump that it’s righteous and humane for healthcare organizations and their medical staff to educate patients and their families about both palliative care and hospice, two distinct approaches.

I was introduced to no cartoon villains in this story, but the more nuanced reality involving deep systemic issues illustrates an even more insidious picture than one animated by a few non-existent Hollywood bad guys.

The truth is that more people should be aware and comfortable with dignified end-of-life care.

Also, connecting financial incentives with patient-centric outcomes can be applauded in the abstract, broadly speaking.

But despite the morally virtuous medical conversations, outraged insiders say incentivizing physicians to push palliative care and ultimately hospice in exchange for explicit financial reward in this way remains ethically problematic, institutionally poisonous and potentially unlawful, especially when the motives of corporate leaders at the top remains so blatantly financial.

“It’s bonuses for bodies,” a medical staffer told me when I met them recently in a New England town.

An array of supporting documents and related internal recordings, including audio from company meetings, helped to corroborate whistleblower claims for this reporting.

“There’s a betrayal of trust in the sacred relationship between patient and provider when there’s financial incentive introduced,” a source stressed, getting to the heart of the matter.

But this is less about questionably-structured bonuses and more about understanding the real-world ramifications of corporate ownership in U.S. healthcare.

The big operators have sown deep, irrevocable distrust among patients and staff. That reality complicates any debate over industry best practices.

‘Undertreatment and Overtreatment’

I submitted an interview request to Optum’s press office last week but after an exchange with a media contact about the nature of my reporting, the dialogue ceased. (On Monday, May 13, after original online publication of this article, the company spokesperson did email me to note how he is working on possibly getting me in touch with a related subject matter expert).

Separately, the American Medical Association (AMA) could not grant my interview request but did direct me to the Code of Medical Ethics, maintained by the organization’s Council of Ethical and Judicial Affairs.

“Payment models and financial incentives can create conflicts of interest among patients, health care organizations, and physicians,” a portion of the opinion within the code highlighted by the AMA for me states. “They can encourage undertreatment and overtreatment, as well as dictate goals that are not individualized for the particular patient.”

The council does not grant media interviews, preferring to let guidance from the code speak for itself, explained R.J. Mills, a media and editorial contact at the AMA.

Hospice, it’s worth noting, became a Medicare benefit about four decades ago, in 1983.

“Despite growth in hospice utilization, fewer than half of Medicare patients elect hospice services, and more than a quarter do not enroll until their final week of life,” the AMA states in its literature about hospice and palliative care.

A press representative at the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine was hopeful the organization could comment on this story after I contacted the professional group late last week but the appropriate party was unavailable by our deadline.

Sick System

With any employee’s workflow, providing bonuses for certain job functions introduces a new dynamic that can reshape culture and complicate motivations.

Constructive hospice cheerleading from most of the medical team appears to be rooted in healthy values, ones we should be championing.

But I asked an insider source about the corporate motivation from UnitedHealth, the insurance industry’s 800-pound gorilla, and Optum’s $470-plus billion Minnesota-headquartered parent company.

“To kill people off before they cost too much – 90 percent of healthcare costs happen in the last five to six years of life,” the whistleblower replied about insurance industry interests, requesting anonymity because they feared reprisal, like many sources for this series and this column. “It’s a cost-saver, not a revenue generator.”

The palliative care/hospice bonus initiative works best, the source also told me, when the company deploys charming medical staff.

Yet it’s important to stress how the overwhelming majority of medical professionals are vying to do right by patients.

“But they’re inside a sick system,” an Optum medical source said. “They’re not corrupt themselves.”

Kool-Aid

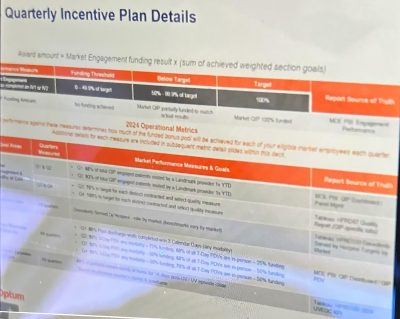

One Landmark/Optum company document I reviewed was headlined “Quarterly Incentive Plan Details,” listing palliative care as a goal area, while defining the measurable related metric as “descendants served by hospice.”

“Performance against these measures determines how much of the funded bonus pool will be achieved for each of your eligible market employees each quarter,” a portion of the document states about 2024 metrics.

As for the benefits of hospice, an insider stressed how they themselves “drink that Kool-Aid completely, 100 percent.”

“We know that patients need to do hospice earlier, way earlier than what they’re doing,” the medical source said. “We know we need to have these death-and-dying conversations earlier in healthcare. But my point is twofold. Number one, it’s illegal. But more to the truth of the matter, it’s immoral because we are facing our patients and their families and when our patients and our families realize that we’re being financially bonused for that decision making, for that referral, that’s immoral, that is shady, and that erodes trust.”

Also, for the record, it’s important to note the difference here between palliative and hospice.

Palliative care is defined by the AMA as that which relieves suffering and improves quality of life for people with serious illnesses, no matter whether they can be cured, whereas hospice provides comfort for those in the final stages of terminal illness, with eligibility defined by public and private payers.

‘Fancy Training’

A medical source painted a powerful picture for me of their experience last fall, after the bonuses were announced earlier in 2023, and how the ethical dilemma plays out in real life.

The New England area medical staffer had forged a relationship with an impoverished local family.

“Their father literally was decaying, like, internally and externally,” the source said. “His skin was falling off. And they kept him alive. And they were poor, but they sought holistic, alternative methods to keep him alive. And they refused to hospice.”

The insider knew the dying patient should ideally be sent to hospice but also understood the complex socio-economic and philosophical considerations that can sometimes propel families to keep relatives alive, regardless of quality of life.

Beyond that, the source knew their employer ultimately wanted the man in hospice.

“But the purpose of that family’s life was to care for that decaying father,” the source said. “And that is not up to me as a provider to interfere. And I was not going to manipulate them with my fancy training.”

Can an easy ethical case be made for trying to promote the virtues of end-of-life care in a case like this?

Absolutely.

But can an ethical case be made for financially incentivizing corporate-employed medical professionals in such an explicit, direct way to potentially manipulate vulnerable people when healthcare is really run by people in business suits instead of those credibly wearing white jackets?

Absolutely not.

‘Palliative Pathway’

Insiders said the unsettling reality of financially-incentivized patient care features coercive company tactics, subjective criteria for hospice qualification and attempts to rebrand the bonuses as a palliative care incentive, all under the implied threat of professional retaliation for staff who don’t comply.

“A lot of the patients are upset when they hear the language,” an Optum medical source told me. “So we’re trained to tell them that we’ve put them on, a quote, ‘palliative pathway.’”

The process of hospice qualification can also lead to different agencies providing conflicting assessments for one patient.

“So even though it supposedly is objective,” the insider added, “it is subjective.”

Sources say Landmark/Optum physicians and physician assistants are not in touch with end-of-life care vendors directly for referrals, and instead hand the process off to internal liaisons, offering separation between medical staff and the execution of the initiative.

That creates problems because physicians and physician assistants tend to know which local third-party vendors are reputable. The level of palliative care and hospice service, from a quality standpoint, can vary to a massive degree.

“They wanted that extra layer,” the source said of Optum, when I asked how mindful the company is around the legalities of the bonus program.

More on that in a bit.

Other Bonus Programs

Less controversial bonus programs were already in place for medical staff before Optum took over.

Landmark/Optum physician assistants might earn in the $140,000 to $150,000 range in terms of annual base salary but they can generate another $35,000 or so through a variety of bonuses.

For example, a physician or physician assistant can earn extra income for providing follow-up at-home care within a certain number of days after discharge from a hospital, a helpful incentive from the patient’s perspective.

Bonus initiatives are also in place related to how many people physicians enroll in the home care program, and for getting certain lab work from patients, to encourage the collection of more data, an ethically dicey area.

If these end-of-life care bonuses were just being endorsed by medical leadership, independent of corporate pressure, perhaps this could just be an intellectually honest, spirited debate about how best to align constructive outcomes with financial incentives in a complex industry.

We’d be able to place some faith in the fact that the overwhelming majority of physicians aim to help patients in their decision-making.

But the context here is that corporate entities, not doctors, now run our U.S. sick care system, largely treating patient care like widget care.

Even if hedge fund-inspired metric-based systems were designed with the best of intentions, and function constructively in other industry frameworks, we need healthcare organizations thinking of patients as human souls, not dollar signs.

Financial officers and artificial intelligence bots don’t swear to the Hippocratic Oath of “Do No Harm.”

Open Secret

As regular readers of this column know, I’ve been investigating a wide array of Hudson Valley area patient concerns since December 2022, after Optum acquired the local CareMount Medical group, which began as Mount Kisco Medical Group in 1946.

A layman on the subject, I didn’t initially grasp how UnitedHealth Group was already on a corporate warpath to try to essentially become U.S. healthcare, or at least monopolize the market, up, down and across.

The organization, through its various units, has its massive teeth sunken into prescription services and data analytics, not to mention its medical and insurance businesses.

But even in gaining insight over the past year-plus about the dangers of corporate-controlled care, and speaking with hundreds of anxious stakeholders linked to Optum East/Optum Tri-State and beyond, I find these latest discoveries particularly unsettling.

Admittedly, much of the detail is new to me, even if not new to many of you.

‘Remuneration’

Within the Optum Southeast/Landmark division in the Massachusetts, Connecticut Rhode Island and New Jersey market, the questionable bonuses are allegedly discussed in brazen fashion.

“They’re openly bonusing,” an Optum medical insider from Massachusetts told me before sharing related documents. “There are PowerPoints, there are presentations, there’s coaching.”

If you’re asking yourself whether it’s legal for healthcare organizations to reward referrals in this way, you’re asking a relevant question.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services maintains fraud and abuse laws that apply to physicians, including an Anti-Kickback Statute, or AKS.

“The AKS is a criminal law that prohibits the knowing and willful payment of ‘remuneration’ to induce or reward patient referrals or the generation of business involving any item or service payable by the Federal health care programs,” the statute states.

‘Shady’ Ways

Even though the company sometimes seems to operate with a sense of impunity, broadly speaking, it is obviously mindful of legalities, as one of the most powerful corporations on the planet.

“I think UnitedHealthcare has structured it in such that we don’t make referrals to a specific hospice service,” a source explained. “We just say, ‘Hey, you know, we have a contact.’ And then that internal contact within the company then reaches out to hospice, a hospice service. So, there’s like a layer that they’re using in a shady way to try to make this legal.”

That said, when internal concerns were raised about dishing out bonuses for end-of-life care conversions, language within company documents started to get tweaked earlier this year, an insider observed.

“They’ve changed the language from hospice bonus to palliative care bonus,” the source noted. “So I know that they’re scared because they’ve changed the language.”

The company also uses its vast well of patient data to efficiently run the initiative, medical staff stressed.

“So only very few people can qualify for this program,” a home healthcare insider told me in a phone interview. “Our patients, as we have been trained, are expected to die within five to six years, according to Big Data. So it’s our job to go in there, to hire very charismatic providers, cultivate a relationship with the patient and/or their family and then convince them to early hospice. That is our job, period.”

‘Cultural Thing’

Totals involved with the hospice financial bonuses don’t necessarily amount to game-changing money for the medical team. A physician or physician assistant might earn in the $1,350-to-$1,500 range for a quarter with current levels of referral conversion “performance.”

But a source said the more corrosive aspect is how the mere presence of the incentive system negatively impacts norms and values of personnel.

A longtime healthcare professional noted how slides are shown at meetings, displaying physician stats.

“It’s not like it’s deal-breaker money, but it becomes a cultural thing more than a money thing,” said a source. “It’s more big money to the administrators and to the nurses.”

Concerns about the bonuses have been brought to the attention of the company’s Ethics & Compliance Department, but the program has continued unabated.

And sources describe bonuses extending to other areas as well, such as incentives ultimately linked to driving prescriptions for statin medications and gathering patient data through lab work, as money-centered care replaces patient-centric care.

“They call it metrics,” a physician stated. “It’s a big word in healthcare that anyone in healthcare hates. Administrators love it.”

Some History

Although new and exotic at Landmark, bonuses for hospice referrals aren’t new in the industry.

In 2017, hospice companies paid $12.2 million to settle kickback claims, the Northern District of Texas office of the U.S. Attorney detailed in a press release at the time.

In 2011, The Washington Post reported on a hospice industry boom, aided by referral bonuses, with patient families initially grateful for hospice guidance, then stung by the loss of trust when learning of the financial link.

“What incentive did the doctor have to put my aunt on hospice?” one person interviewed for the piece lamented.

Unrelated press reports last year also noted how the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) alleged that HCA Healthcare pressured patients and their families about hospice, a charge the hospital system denied.

The union claimed the HCA “put pressure on families to choose hospice in order to reduce inpatient mortality rates and maximize profits,” the publication Hospice News reported last June.

As for the bonuses linked to end-of-life care at Landmark/Optum, it’s not just about this one questionable policy.

It’s about a grotesque money first, second and last culture that seems to permeate all decision-making when corporate bean counters run healthcare instead of doctors.

Commodifying patient health to the extreme has been largely normalized.

“It’s such a sacred conversation to have with a patient, and it’s taboo,” a New England area source concluded to me about the delicate dialogue with patients and their families regarding hospice, and the corrupting influence of financial incentives. “It’s taboo for the patient. It’s taboo for me as a provider. So you have to do it right.”

Backdrop

This chapter of the story unfolds as the Department of Justice (DOJ) is reportedly investigating UnitedHealth’s $3.3 billion acquisition bid for Amedisys, a home health, hospice and palliative care operator.

Separately, in February 2023, Optum finalized its $5.4 billion acquisition of LHC Group, a home health and hospice company.

I also reported in February about internal documents that confirmed a DOJ probe into alleged monopolistic practices within United/Optum, which affiliates with an eye-popping estimate of about 10 percent of U.S. physicians.

Bloomberg News reported in April that UnitedHealth Group executives sold more than $100 million in stock before the federal antitrust investigation became public, sparking questions about disclosure and insider trading protocols.

“Shares of UnitedHealth fell 5.2% in two trading sessions on Feb. 27-28, after the probe was widely reported in financial media,” the Apr. 11 Bloomberg article noted. “It was first reported Feb. 26 in the Examiner News, a local publication in New York state.”

In a subsequent piece I noted an emerging national effort to address the Corporate Practice of Medicine, and a looming legislative initiative by U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) to potentially address the systemic issues.

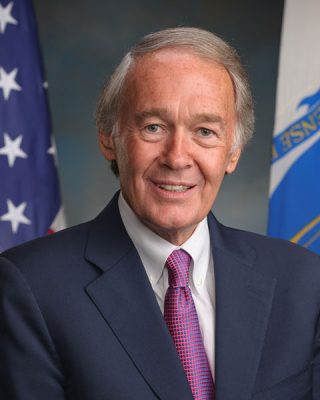

News also emerged in April that Sen. Edward Markey (D-Mass.) released a discussion draft of a bill, the Health Over Wealth Act, which would require greater transparency in healthcare entity ownership.

The legislation would enact safeguards to protect workers and “preserve access to health care; and elevate the voices of workers and communities in regulating health care and monitoring hospital closures and service reductions,” according to a summary on the senator’s website.

As for the February cyberattack on Change Healthcare (acquired by UnitedHealth for $13 billion despite a 2022 federal effort to thwart the deal) the ensuing mess has highlighted just how vulnerable our private patient data and the wider system is to threats, triggering billions in stalled payments and industry chaos.

UnitedHealth acknowledged last month paying an ultimately ineffective ransom payment before hackers stole data from a “substantial proportion” of Americans on Feb. 21, a Reuters article detailed.

Massive Optum layoffs were also reported in the third week of April, with some sources complaining to me of medical units cut down to the bone, or worse.

More background

These local enterprise columns about CareMount/Optum have covered or uncovered an oppressive local physician employment contract; a disastrous phone system; a related emergency room crunch; alleged double billing; copay confusion; a scathing internal survey; data privacy breaches; attorney general scrutiny; suspect COVID-19 testing charges; predatory marketing tactics; Medicare Advantage-related profiteering concerns; state lobbying efforts; a disconcerting doctor shortage; the troubling mix of healthcare with insurance services; bruising layoffs; the unethical banning of unwell patients; the denial of patient medical records, and a deceitful medical billing plot alleged by a whistleblower.

(On Apr. 23, the Federal Trade Commission announced a rule banning non-competes nationwide, aiming to boost worker freedom and innovation.)

Records I’ve secured through the Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) have detailed frustrations with CareMount/Optum’s questionable billing system, as scores of patients have appealed to state Attorney General Letitia James’s Health Care Bureau for help over the course of many years.

On Apr. 29, James (alongside a coalition of 22 attorneys general) announced how she was urging UnitedHealth to address the repercussions of the cyberattack on Change Healthcare, with its impact on millions of patients and providers nationwide, causing delays in care access and financial strain on healthcare facilities.

In April I also received word from sources that the outsourcing of the pre-authorization process to IKS, an Indian firm, was wreaking havoc for staff and local patients. (Optum Tri-State includes the old CareMount Medical, ProHealth New York, Riverside Medical Center and Crystal Run.)

Dr. Scott Hayworth, former CareMount CEO, left the company at the end of 2023. An online search shows Hayworth listed as chairing the IKS advisory board.

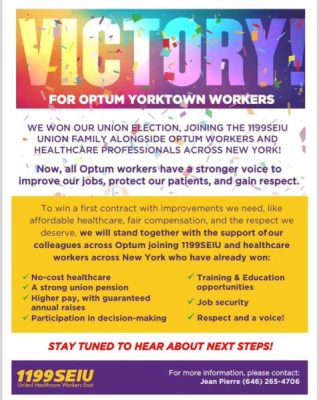

In addition, there’s been growing union activity in the area among beleaguered Optum employees.

I received confirmation in early April that Jefferson Valley workers were the latest to unionize, followed by Carmel a couple weeks later after Brewster warehouse/lab staff blazed the trail last year.

Organizing efforts have been coalescing across the Hudson Valley at former CareMount buildings, according to union sources, despite alleged union-busting efforts.

But let’s get back to where we started – with events leading up to last week’s public announcement of some long-brewing, potentially encouraging local improvements, with caveats.

‘The Care You Need’

It’s worth noting that we published a response in April from Optum Tri-State President and Chief Medical Officer Dr. Jonathan Nasser, who had pushed back on my report about the whistleblower’s formal complaint on the alleged billing plot, which was filed in February with the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) through the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

“We routinely engage with clinicians who may be new to value-based care to undertake necessary training to ensure legally compliant, supported coding that results in improved outcomes for patients,” Nasser stated in a portion of a letter to the editor to The Examiner, referencing a report that we firmly stand by. “The recording you referenced in your Mar. 18 article about Optum was an example of an interactive training session designed to further that aim. Any suggestion otherwise is categorically false.”

Nasser joined the company last year when his Hudson Valley area medical group, Crystal Run Healthcare (where he served as president) was acquired by Optum.

I previously obtained an e-mail he sent to his Optum Tri-State colleagues on Apr. 9 where he cited organizational upgrades, and plans to continue and improve, citing investment in the phone system, expanded patient access to clinicians, facility enhancements and better employee compensation and culture.

“We’ve been spending intentional time listening to your needs and concerns,” Nasser wrote in the company e-mail, provided to me by a local doctor through a trusted intermediary. “We are grateful for your candid feedback. Our goal is fostering an environment where staff want to work and practice medicine over the long term.”

In a YouTube message late last year, speaking from his perch as Crystal Run Healthcare president, Nasser struck a sympathetic tone.

“We don’t always get it perfect but we really do care and we’re working hard to be the best possible place for all of you to come and be healthy,” he told the community.

In fact, in last week’s May 8 public announcement to patients (which some say they did not receive) Nasser again acknowledged past medical group shortcomings, and detailed the enhancements to the phone system, increased access to clinicians and investments in facilities and software, not to mention new regional leadership.

“We have been listening to feedback from patients and care teams and are disappointed our operations may have created frustration, including our phone system and wait times to see certain physicians,” said Nasser, who I happen to know has privately reached out to individual patients dealing with issues, something I learned unsolicited.

Critically, Nasser referenced the urgent demand to expand access to clinicians in his message to patients.

He noted, for example, how since January 2023, the company had hired more than 120 clinicians in over 20 specialties for CareMount.

But much more hiring, it seems, will be needed, given the continued exodus of local Optum doctors.

“Our teams have been focused on creating additional appointment slots both in person and virtually to get you the care you need, when you need it,” Nasser, who holds a master’s degree in business administration from Duke University, stated in his e-mail to patients.

More Good News

On a related note, a local patient recently told me, also unprompted, about their positive experience at CareMount/Optum.

At their physical exam, the patient was seen on time, for a full 45 minutes, and everyone from physician to medical assistants “went out of their way to be caring, kind and friendly.”

She also received a courteous phone call from one of the physician’s medical assistants, providing her with negative lab results that were also added to the patient portal.

“I noticed a major departure from the past on these and all other markers, both at the physician’s office and the lab at Building 90,” the patient explained.

These are small wins – what should be expected – and the larger systemic crisis rages on.

I do realize the problems are many moons from being solved. But I think we’ve clearly seen how we should never assume a problem is beyond trying to fix; issues can always get better, or get worse.

Sunlight can still help disinfect the most insidious public viruses.

Running the Point

I hope Nasser is as sincere as he sounds in the messages.

It seems clear that some substantive local action has really been taken, despite the vast structural issues.

Fingers crossed.

I’m cautiously optimistic about the potential for steady, concrete progress, and you should continue to expect and demand exactly that.

That said, many patients reacted to last week’s news with understandable, deep skepticism, pointing to current physicians who plan to leave by the end of this year, if not sooner, and the broader, systemic problems.

“Same circus, different clowns,” one patient quipped about the management changes in an e-mail to Examiner Editor-in-Chief Martin Wilbur.

Personally, I believe deploying the right point guard can make a profound (albeit incomplete) difference.

But, yes, fixing some of the structural issues remains deeper than local leadership.

While few of us are experts in the world of day-to-day healthcare operations – it must be almost incomprehensibly complex to sail a smooth ship – we can all easily recognize the massive front-end problems.

Executing a treatment plan for corporate sick care is difficult, but identifying the symptoms of the disease rests in plain sight for us all to see.

Healthcare Reporting

On a personal and professional note, a quick update on this chapter in the series.

There can always be a sequel or an epilogue.

However, for now, I’m pressing pause on the active investigation because of bandwidth limitations, needing to focus on running this community news outlet. (But there’s a significant but – we have a grant application pending with a national journalism organization that could allow Examiner Media to eventually expand our probe to a teamwide project for a year, a potential key to unlocking a treasure trove of buried details related to corporate healthcare in the region.)

When I began all this work in late 2022, I wanted to raise awareness, agitate for legislative action, inspire more coverage, empower healthcare employees and help generate a robust public response.

I’m gratified to know our tiny news organization has played a modest role in some of that unfolding, even as the massive, ongoing problems remain vast and overwhelming.

Thankfully, there are many world-class journalists who have been digging into the bigger story of corporate healthcare for a long time.

Just last week, STAT News was named a Pulitzer finalist, with reporters Casey Ross and Bob Herman exposing in November how UnitedHealth “pressured its medical staff to cut off payments for seriously ill patients in lockstep with a computer algorithm’s calculations, denying rehabilitation care for older and disabled Americans as profits soared.”

In fact, there’s been many blockbuster healthcare pieces published recently.

New York Times journalist Chris Hamby authored a major article in April that showed how “a private-equity-backed firm has helped drive down payments to medical providers, drive up patients’ bills and earn billions for insurers.”

Just last week, The Oregonian reported the latest about Optum’s disastrous impact in the state, with doctorless Eugene area patients in healthcare “purgatory.”

Meanwhile, former Cigna VP-turned-whistleblower Wendell Potter penned a piece for his Substack newsletter in late April about how employees in the Philippines play a key role in denying care for American beneficiaries.

Much more is coming, too.

Final Thoughts

I started to learn new information in recent weeks that paints a problematic picture of the events that led up to more than 250 area physicians selling their shares in our local healthcare organization, and Optum’s ultimate acquisition.

There were hundreds of good doctors who were unable to resist (understandably so) the power of the corporate vortex, either unsure of Optum’s threat to patient care or reasonably concluding they possessed limited choice.

We’ll hope to help tell that story eventually in more vivid detail. There’s definitely more sunlight to shine – Optum does not maintain a monopoly on the problem of healthcare operators valuing shareholder interests over patient interests.

In a time of extreme divisiveness, I believe there’s actually a real opportunity with this issue to forge creative political coalitions, marrying progressive and populist distrust of crony capitalism with my preferred brand of common-sense, centrist problem-solving.

I’m sending the region’s executive team my most genuine wish for better days ahead, as they hopefully work to empower doctors and staff to deliver the compassionate, patient-centric, holistic healthcare we desperately need.

No easy task.

I’d love to eventually write an installment about how new local leadership triumphed in this way.

Let’s hope the facts allow for that tale to be told.

Keep up the good fight, everyone, including those on the inside.

We’ll be watching.

Adam Stone is the publisher of Examiner Media.

Adam has worked in the local news industry for the past two decades in Westchester County and the broader Hudson Valley. Read more from Adam’s author bio here.