National Shame, Revisited: Our Digital Editor’s Take on Sandy Hook, Gun Violence

Opinion Advocates for ideas and draws conclusions based on the author/producer’s interpretation of facts and data.

Today marks a dubious double milestone — the tenth anniversary of the shooting spree at Sandy Hook Elementary School and the 30th anniversary of the shooting spree at Bard College at Simon’s Rock, my alma mater.

When I first pitched the idea of republishing this essay about these incidents and gun violence in general to our publisher, Adam Stone, I confess to being a bit ambivalent about it.

Regrettably, almost nothing has changed on the subject in the past year since it was originally published last December. The number of shootings, and the subsequent number of fatalities and survivors whose lives have been forever changed, have only continued to grow unabated.

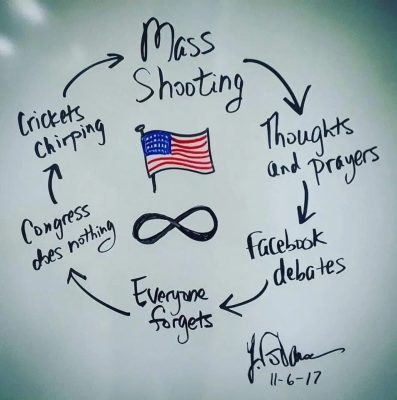

Uvalde. Buffalo. Chesapeake. Highland Park. Colorado Springs. The more things change, the more they stay the same. It feels like the movie Groundhog Day — except we’re not yucking it up in a Bill Murray comedy, but rather playing out a real-life Squid Game just trying to survive in a grotesque tragedy of our own making. But, as in Groundhog Day, we are collectively condemned to repeating what we’ve been doing to ourselves on an infinite time loop until we get it right.

It’s precisely that reason which made me realize my essay is, sadly, just as relevant now, if not more so than last year.

While we remember and honor those who died on this date, and in all of the mass shootings that have heretofore rocked our society, here’s hoping that, as this year draws to a close, we finally start getting it right in ’23.

It happened again.

When news broke across my TV about the shooting spree at Oxford High School in Oakland County, Michigan, it brought everything back.

For good and for ill, guns have played a recurring, though significant role in my life.

My grandfather was a Philadelphia police officer. Not only did he carry a firearm on duty, but he enjoyed guns recreationally. An expert shot, he even helped coach members of the US Olympic rifle team, I was told. His love of guns as both hobby and sport was passed along to my father, who, for much of his life, competed in all manner of target shooting — trap, skeet, pistol, small-bore, high-power, black powder — winning truckloads of trophies and awards along the way. Every winter, he faithfully hunted deer with my uncles in the Poconos (though, thankfully for the deer in my home state, with much less success than his target shooting).

As the son of a gun enthusiast, I grew up in a home with firearms and their myriad accoutrements. I used to joke we had enough weapons and ammo to arm a CIA-backed revolution in a small Latin American country. But all of it legal and properly maintained. A responsible gun owner, my father always kept them locked up and drilled it into my sister’s and my heads never to touch or go near them. When we were older, my father introduced us to his hobby, bringing us to the various ranges at the gun club to which he belonged and teaching us how to shoot. We both scored a few trophies and awards of our own.

Despite my father’s best efforts, he failed to pass the love of the sport onto me, but what stuck with me from all the time I clocked with him at the gun club was the social dimension that accompanies most hobbies. My father befriended people from all walks of life: lawyers, carpenters, housewives, judges, students, dentists, retirees — people he’d probably never have met otherwise — and people you wouldn’t necessarily peg as being gun enthusiasts.

Though I had bid a fond farewell to everyone at the gun club and target shooting by the time I entered high school, I would have a vastly different experience with guns a few years later. During my senior in college, on a snowy afternoon just a week before Christmas, a classmate took advantage of a then-legal loophole that allowed out-of-state residents to purchase firearms immediately without restrictions. That evening, he shot his way across our bucolic New England campus with a Soviet SKS military assault rifle he bought for $150 cash at a nearby sporting goods store — killing a professor and another classmate and gravely wounding several others before a gun jam miraculously curtailed his rampage.

The tragedy at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, occurred on the 20th anniversary of the shooting at my college (Bard College at Simon’s Rock, in neighboring Massachusetts). When news about Sandy Hook broke that morning, a sick feeling took root in my stomach. I assumed there was some connection — some copycat heinously capitalizing on the anniversary of the Simon’s Rock shooting. As details of the Sandy Hook massacre came to light later in the day, I was proven wrong. That school shootings have become so numerous that they’re now falling on the same dates by coincidence and not by design is perhaps the most tragic commentary one could make on the subject.

The shooting spree at Simon’s Rock was one of the first-ever school shootings — several years pre-Columbine. And so, while it garnered significant media attention, it was simultaneously dismissed as a cosmic fluke and tragic outlier — a notion we were all too happy to embrace. Who could have possibly imagined then that “active shooter drills,” “lockdown procedures,” and “school resource officers” would eventually become as de rigueur as homecoming and senior prom.

For the past 20 years, I have served as an auxiliary police officer (now lieutenant) in the NYPD. One night when I was on duty in 2007, two fellow auxiliary officers in my neighboring precinct, one of whom I knew socially, were gunned down (shot in the head) while on patrol in Greenwich Village by a heavily armed, deranged man fleeing a pizzeria around the block that he just shot up in a rampage. Like all of the 5,000 volunteer auxiliary members of the service in the NYPD, Auxiliary Officers Eugene Marshalik and Nicholas Pekearo put their lives on the line for free to serve their city each time they suited up in the department’s iconic uniform.

Regardless of your position and feelings on guns, the fact remains they’re a part of our society — including here in Westchester, as The Journal News illustrated when it published its controversial map of local gun owners with their names and addresses in response to the Sandy Hook massacre. With more than 44,000 people in Westchester, Rockland, and Putnam (or one out of every 23 adults) licensed to own a handgun, chances are if you’re not an owner yourself, you are no more than one or two degrees removed from one — whether you know it or not.

In 2020, there were more than 600 mass shootings (defined as four or more people injured or killed, excluding the perpetrator) in the US; the latest available data suggests 2021 is on track for a similarly ludicrous total.

No matter your political stance on gun ownership, one thing we can all agree on — we must agree on: This is not a sustainable course for our society. While various solutions proffered by the right and left may be imperfect, insufficient, or otherwise flawed, the worst thing we can do is nothing. We have to try something. If it doesn’t work, then we try something else; we must keep going down our collective list of ideas until we can finally move the needle on curbing this uniquely American phenomenon.

What we can’t do is allow ourselves to grow numb to the shock and horror of these unspeakable tragedies. To do so would not only normalize them but condemn ourselves to a future of compounding social ills, the likes of which we might never recover from.

A few years ago, my college hosted a weekend memorial gathering in observance of the 25th anniversary of the shooting. All members of the Simon’s Rock community — alumni, parents, faculty, staff — who were present for or affected by the shooting were invited to return to campus for a weekend of remembrance, reflection, fellowship, and healing. Many flew in from far and wide to attend; for some, it was their first time back to the college since they had left.

While I’ve quietly carried my own scars from that day, what I found simultaneously reassuring and alarming was the pervasiveness, lengths, and depths of the shooting’s effects on so many others. Friends and former classmates talked about their battles with anxiety, depression, PTSD, substance use, and more. These many years later, I thought maybe I was an outlier for having the incident still weigh so heavily on me. I was comforted to know I was not alone but distressed to see so many people I care so deeply about remain in such profound pain — and still struggling fiercely to this day. One friend and classmate spoke about how the emotional aftereffects have derailed her career on multiple occasions. Another recounted how neighborhood kids innocently setting off firecrackers next door one recent summer evening triggered him into a frenzy, believing he and his family were suddenly under armed assault the way he had been that snowy December night while studying for final exams in the college library.

When I watched Oakland County Prosecutor Karen McDonald speak about the shooting at Oxford High School, her most insightful remark, regrettably, was about how the emotional injuries from the event were going to remain with everyone from the school and their community long after the physical injuries to the survivors heal. Such was the case for us at Simon’s Rock. Every time I see a new shooting like this take place, I think about the incident’s impending life cycle and what everyone involved will soon but unknowingly be facing in the days, weeks, months, and years ahead.

Surveying the extent to which the shooting at Simon’s Rock has impacted so many among the greater college community, I take note of its ripple effects in impaired mental and physical health, lost productivity, economic and financial repercussions, strains on marriages and other personal relationships, and more. Take that and multiply it across the nation for every other mass shooting at a school, workplace, mall, and church from the last thirty years, and the cumulative, compounding toll and devastation levied on our society are utterly incalculable.

But whatever we do, let’s skip the “thoughts and prayers.” It’s become a self-serving, perfunctory trope bordering on punch line.

A punch line, at least, until it happens again.

Robert Schork is Examiner Media’s Digital Editorial Director.