Michael Magee’s Belfast Book Packs a Punch

Review An assessment or critique of a service, product, or creative endeavor such as art, literature or a performance.

By Michael Malone

To read about Ireland is to read about how quaint it is. How green the landscape is, how warm the people are, how tranquil the vibe is.

To read about Ireland is to read about how quaint it is. How green the landscape is, how warm the people are, how tranquil the vibe is.

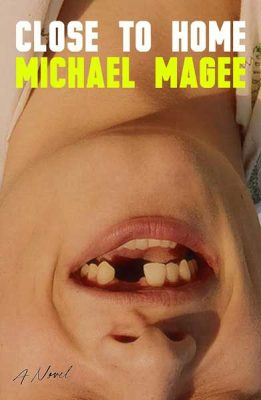

It is a much different Ireland in Michael Magee’s “Close to Home.” Granted, the book is set in Northern Ireland, and the Belfast he depicts is hopeless. The older generation suffers from severe psychological problems related to The Troubles that once ravaged Northern Ireland. The younger generation cannot find jobs and consumes prodigious quantities of alcohol, and seemingly just as much cocaine. It is, oftentimes, violent.

The novel starts with a bang: “There was nothing to it. I swung and hit him and he dropped. A girl came flying forward and pushed me: What’d you do that for? The lad was lying there and I was standing over him and there were people all around me making noise. By the time I got away from the tussle, two Land Rovers had pulled up. A jaded-looking peeler with a receding hairline came towards me.”

Sean is in his early 20s. He was at a party, and some young men were harassing him. It was a class thing, a common theme in the novel. His adversaries were posh and he comes from a single-parent home, with a mother who cleans houses. The rich boys were teasing him, so he punched one of them.

The cops come, and Sean goes to court. He avoids prison, but must embark on a rigorous community service routine, involving landscaping at a graveyard and sweeping up at a church, among other busy work, that stretches the length of the book.

Sean studied literature at college in Liverpool, then returned to West Belfast, and pieces together frustrating jobs, including bartending and being a barista. He’s a decent young man, trying to do the right thing and get his life sorted out. His family is dysfunctional. His mother is sweet and loving and drinks too much. His brother Anthony is alternatively loving and scary, and drinks way too much. His father, an IRA veteran who abused Anthony, is out of the picture, but Sean stalks him online, and does the same with his stepsister Aiofe.

The reader hears frequently about how Sean is a books guy, but Magee does not develop that aspect of his personality. Telling us which authors and stories Sean reads and adores would tell us a lot about his character, but it’s not until page 175 that an author is named, as Sean “sat up late reading Alice Munro stories.” It felt like Magee wanted his main character to be a literary sort, but could not be bothered to fully flesh him out in that regard.

Sean reconnects with his girlfriend from their teen years, Mairead. She went to Queen’s University and hung with the rich, brainy kids and plans to move to Berlin and work in film. Sean and Mairead sort of resume their old relationship, but things get complicated. Still, she’s a positive influence amidst the laggard lads he hangs out with, who urge Sean to have one more beer, one more line of cocaine and not worry about work the following day.

Magee writes in the local dialect. Police are peelers. An apartment is a gaff. To throw up is to boke.

He is the fiction editor at the Belfast literary magazine The Tangerine and got his PhD in creative writing at Queen’s University. “Close to Home” is his first novel.

Published this year, the book has an impressive 4.14 average, out of 5, on GoodReads. The New York Times review said, “By presenting dialogue without quotation marks and employing single-line, staccato paragraphs, Magee’s yarn unspools like a story told over a couple of pints. The result is an intimate, dizzying onslaught that highlights the contrast between fear and joy, love and hate.”

The Guardian called “Close to Home” “taut and impressive,” and “that rarest of things: a genuinely necessary book.”

I liked “Close to Home,” though not as much as the critics did. Magee’s writing is good. The novel’s inciting incident, the punch, packs a wallop, but there’s not a whole lot of plot. It is more of a character study than a story-driven novel, and Sean doesn’t quite have the personality to deliver on that front.

Magee does do an interesting job of illustrating how The Troubles affected the residents in Belfast, and will continue to do so for years. Sean’s mate Ryan “had to explain…what he’d done during the conflict, but he hated what the war had done to him, and hundreds of people like him, men and women who fought for all that time, who had done things they would have to live with for the rest of their lives, and for what?” Magee writes.

As Sean does his community service in a graveyard, he sees the grave of Bobby Sands, the IRA soldier who died in prison from a hunger strike and is buried with two other “Volunteers,” as their shared gravestone says.

“There was no epitaph,” he writes. “No lines from poems, no quotes. Nothing to distinguish them from the people who had been buried alongside them. It was better that way, I thought. This was a man who had sacrificed his life for the cause, kind of thing, but also, here was a man who was from where I was from, who ran about the same streets I ran about. I felt that deeper than I had ever felt anything, but it was fleeting, and by the time I stepped away from the memorial, the feeling had already receded.”

“Close to Home” is not a fun read, but it is often moving. A slim 278 pages, it punches above its weight.

Journalist Michael Malone lives in Hawthorne with his wife and children.

Corrections:

Sourcing & Methodology Statement:

References:

Examiner Media – Keeping you informed with professionally-reported local news, features, and sports coverage.