Mercy Me, Lehane’s Latest Packs Punch

Review An assessment or critique of a service, product, or creative endeavor such as art, literature or a performance.

By Michael Malone

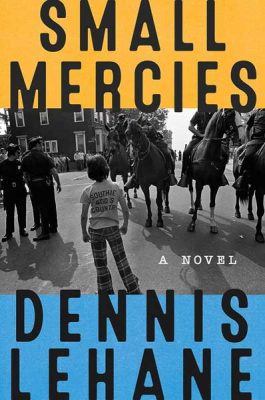

“Small Mercies,” the latest novel from Dennis Lehane, is a look at the Southie neighborhood of Boston in the summer of 1974.

Boston’s infamous busing struggle, which would see students bused from Black neighborhoods to white schools, and white students bused to Black schools, is set to begin in September, and the residents of Southie – Irish American, working class, hardly progressive – are not having it. They don’t want their kids bused to a school in the Black neighborhood of Roxbury, and they sure as hell don’t want Black kids in South Boston.

Boston’s infamous busing struggle, which would see students bused from Black neighborhoods to white schools, and white students bused to Black schools, is set to begin in September, and the residents of Southie – Irish American, working class, hardly progressive – are not having it. They don’t want their kids bused to a school in the Black neighborhood of Roxbury, and they sure as hell don’t want Black kids in South Boston.

A historical note before the novel begins shares how a judge ruled in June 1974 that the school system “systematically disadvantaged” Black students, and that busing would begin in early September.

“It was very hot in Boston that summer, and it seldom rained,” teases Lehane.

Mary Pat Fennessy raises her daughter in a Southie project. One son died of a drug overdose. Two husbands departed. So it’s just Mary Pat and Jules.

Then Jules, who is 17, disappears, and Mary Pat sets out to find her.

Organized crime has an outsize presence in Southie. Marty Burns is the local crime boss, perhaps a stand-in for Whitey Bulger. When Southie residents have an issue, they go not to the police but to Marty and his henchmen.

Jules was involved in a relationship with Frank Toomey, a Burns-gang thug known as Tombstone. Toomey is married and Jules threatens to bring attention to their affair.

Mary Pat, who is one tough broad, works at a hospital with a Black woman known as Calliope, whose young son is killed in Southie the same night Jules goes missing. Auggie’s car broke down in the neighborhood, and young residents out for a few beers, including Jules, did not take kindly to a Black man walking around in Southie.

Investigating Jules’ disappearance is a detective named Bobby. Bobby served in Vietnam before joining the Boston Police Department. He recalls killing a couple young soldiers in Vietnam.

“Call them gooks, call them n——, call them kikes, micks, spics, wops or frogs, call them whatever you want as long as you call them something – anything – that removes one layer of human being from their bodies when you think of them,” Lehane writes. “That’s the goal. If you can do that, you can get kids to cross oceans to kill other kids, or you can get them to stay right here at home and do the same thing.”

Lehane offers an unflinching portrait of racism in Southie, and it is quite disturbing. He grew up in Dorchester, another working-class Boston neighborhood, and his books include “Mystic River,” “Gone, Baby, Gone” and “Shutter Island.”

In 2016, another novel named “Small Mercies” came out. That was by Eddie Joyce, and was about a Staten Island family still figuring life out years after their son was killed on September 11. Joyce has something of a Boston connection, too; he went to Harvard.

Lehane’s “Small Mercies” at times reads like a historical novel, in terms of the busing initiative. Senator Ted Kennedy plans to address the massive, angry crowd outside City Hall. Mary Pat “is baffled by the back of Teddy’s suit. It’s almost completely white now, as if he’s been s— on by a flock of birds. It takes her a second to realize it isn’t bird s—,” Lehane writes.

“It’s spit.

“The crowd is spitting on a Kennedy.”

Lehane’s style is such that, if you’re me, you read the first paragraph of the novel, and you know right away it is written in your language. “Small Mercies” is a brutal yarn that ends well for no one. And I was along for the bumpy ride from page one.

I’m not the only one. “Small Mercies” has a sky-high 4.33 out of 5 on GoodReads, with almost 29,000 people rating it. The New York Times said, “The book has all the hallmarks of Lehane at his best: a propulsive plot, a perfectly drawn cast of working-class Boston Irish characters, razor-sharp wit and a pervasive darkness through which occasional glimmers of hope peek out like snowdrops in early spring.”

NPR called the novel “incredibly timely.”

It continues, “At once a crime novel, a deep, unflinching look at racism, and a heart-wrenching story about a mother who has lost everything, this narrative delves into life in the projects at a time when the city of Boston struggled with the desegregation of its public school system – and a lot of residents were showing their worst side.”

As the novel winds down, Mary Pat shows up at Calliope’s house after a memorial for her slain son. If the reader thinks a feel-good moment will happen, mothers bonding over the loss of their children, that’s not how Lehane rolls.

“Go back to your neighborhood and sit with your monster friends and get yourselves all worked up to stop us from attending your precious school or whatever,” Calliope tells Mary Pat. “But bitch, we’re coming whether you like it or not.”

Journalist Michael Malone lives in Hawthorne with his wife and two children.

Examiner Media – Keeping you informed with professionally-reported local news, features, and sports coverage.