Life on the Line: White Plains Woman Needs New Liver to Survive

Emotions ‘Run the Gamut’ in Family’s Hunt for Healthy Organ

Gail Jasne, who is battling end-stage liver disease, received dark news about a week ago that also could have potentially delivered her light. Her phone rang and a friend was on the other line with an urgent and dramatic development to share.

Gail Jasne, who is battling end-stage liver disease, received dark news about a week ago that also could have potentially delivered her light. Her phone rang and a friend was on the other line with an urgent and dramatic development to share.

The friend’s brother, 40-year-old Daniel Yglesia, was suddenly brain-dead in a South Carolina hospital, either from a fall or a heart attack.

Anguished, the friend and her family were trying to donate Daniel’s organ to Gail, familiar with her desperate recent efforts to locate a match.

Gail, a 66-year-old White Plains resident, needs a new liver to survive.

“Emotions run the gamut from hoping the liver comes through to feeling guilty that the donor had to die, fear that it would not be a match or done in time and the list is endless,” Jasne said of her thoughts while the dramatic events of last Sunday unfolded, which she recounted for me the next day.

There’s not yet a happy ending to this sad story: Daniel died and his liver wasn’t viable.

Record Books

While the United States has broken its own records for organ donations in each of the past dozen years, with 42,800 transplants in 2022, more than 100,000 people remain waiting for a lifeline.

Gail is one of those 100,000.

In fact, in terms of liver transplants specifically, there are more than 17,000 patients on the waiting list in the U.S. but only enough donated livers to perform about 5,000 transplants per year.

About 6,000 Americans die annually while awaiting organ transplants.

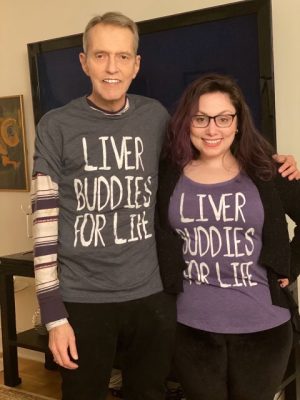

But this isn’t just Gail’s battle. The most prominent members of Team Gail are Hugh Jasne, her husband of more than 30 years, their eldest daughter, Allison, a Philadelphia schoolteacher, and the baby of the family, younger daughter Jenie, a mechanical engineer in Boston.

From a psychological standpoint, one of the most emotionally complex pieces of the mental puzzle for someone in Gail’s position is first checking with direct family members on whether they’re a match.

Networking

Gail was approved two months ago, in January, for the national donation recipient list, a fluid database maintained by the United Network for Organ Sharing. It contains medical information such as blood type, body size, and medical urgency.

As for family, Hugh was too old to be Gail’s donor. Allison wasn’t a blood match. Jenie was rejected for medical reasons. Nieces and nephews weren’t blood-type compatible. No viable family donor candidates emerged.

I asked Gail how she absorbed that realization. She said she felt both “disappointed and relieved.”

“As a parent, it is my job to protect my children, not put them in harm’s way,” Gail observed. “As a spouse, the same feeling. But I know that I would do it for them in a heartbeat if they needed a liver.”

That’s for sure.

It’s been a full-court press for the Jasne clan, working to support Gail in any way possible in dealing with her nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, which is basically liver inflammation, sometimes referred to as a “fatty liver.” She received the definitive diagnosis last summer.

Fangs Out

Gail and Hugh originally met on a blind date 32 years ago, a night before New Year’s Eve, on Dec. 30, 1990. They’d been talking on the phone for weeks before meeting.

Hugh quipped to a mutual friend before the date that unless Gail had fangs, he was intent on marrying her.

“I brought fangs on our date, just in case he turned out to be weird,” Gail recalled lovingly.

I’ve been acquainted with the Jasne family since the summer of 2011, around the time of Examiner Media’s entry into the White Plains market. Gail reached out to me that July with an unsolicited e-mail congratulations, one stranger to another.

The gesture tells you a lot about Gail.

Caring, curious and practical, the friendly outreach established communication with the new paper in town for the family legal business, as well as for a daughter with a writer’s aspirations.

Allison, about to be a high school freshman at the time, earned an assignment as our teen correspondent.

Hugh, a former assistant district attorney in the Bronx, is a longtime White Plains lawyer, in private practice, with Gail serving as office manager for the past three decades. He even helped me one time in a brief legal scrape with an obnoxious competitor.

‘Major Torture’

I asked Hugh what the ordeal has been like to endure, as an adoring husband.

“I’d say it’s quote, ‘everything and nothing,’ meaning Gail really does try and keep a stiff upper lip, I think especially around me,” Hugh explained to me in a phone interview last Wednesday. “But I think probably the most major torture is that we know that right now, knock on wood, she’s running around pretty much fine, but you recognize that at any minute it can go downhill very quickly. So it’s almost like you’re playing Russian roulette as you sit there. I mean, you’re waiting for the bullet to come into the chamber.”

While the circumstances have been excruciatingly painful for Hugh — he described a feeling of his life’s foundation potentially crumbling to bits – it’s also caused him to become more introspective.

The hard-charging attorney might not change his ways so dramatically where he’ll stop to smell all the roses, all the time. But he said there’s now a chance he’ll stop to smell some of the roses, some of the time.

There’s also been another enlightening lesson, amidst the darkness, as unexpected acquaintances and others have offered profound gestures of kindness and support along the way, in the search for a donor match.

“I think there are a couple of bright spots, and one of them is that you feel a little bit better about humanity,” Hugh told me. “Because you know that with all the insanity that we are now currently living with, there really are a lot of good, caring, giving people in the world.”

Family Vows

Allison, for her part, moved her wedding plans up to April, with her mom’s health in mind. I asked her in a phone interview last Tuesday what the process has been like, as the adult daughter of a mom fighting for her life, seeking a donor match.

“Yeah, I think it’s a lot of steps,” replied the 2015 White Plains High School graduate. “And then false starts and then more paperwork, and then waiting again, and then hope and then paperwork. I described it, I think, yesterday, that it’s like you’re pregnant, but we don’t know when it started or when it’s ending.”

The family even recently started a website – www.

On the site, readers learn the basics of Gail’s case, and the special person out in the world she’s urgently trying to find: a physically and mentally healthy donor between the ages of 18 and 59, with a B or O blood type.

“As a living partial liver donor your remaining liver will regenerate to full size in about 12 weeks,” Gail explains on her site, also noting how living donors don’t need any medication just a few weeks after surgery.

A potential donor for Gail can live anywhere – there’s no New York residency requirement or otherwise – and her insurance and various grants are set up to cover all costs.

Recent History

While the world’s first-ever liver transplant was successfully completed in 1963, that patient died of pneumonia just weeks later. It wasn’t until far more recently, in the 1990s, when the procedure started to become progressively more commonplace.

The U.S. even eclipsed a numerical milestone last year: a million total organ transplants.

In Gail’s case, she’s working with Columbia’s NewYork-Presbyterian living donor medical team.

Living donor liver transplantation involves a healthy person donating a portion of their liver to a recipient. Recovery for the donor usually takes just a matter of weeks, whereas the post-surgery process for the recipient is more likely to be measured in months.

Donor recipients receive immunosuppressant medication to avoid rejection of the transplanted liver.

While living donor liver transplants remain relatively rare — there were only 603 last year — the numbers have been steadily climbing for decades, starting with just two in 1989, according to national statistics I found inside a database on the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network’s website.

For Gail, access to an elite medical institution at Columbia provides ample reason for hope.

The Center for Liver Disease and Transplantation at Columbia is an innovator in the field, improving recovery times with minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery. As a matter of fact, Dr. Jean C. Emond, Columbia Surgery’s chief of transplantation, helped pioneer the liver transplant procedure in the 1980s.

Dr. Alyson Fox, medical director for Columbia’s Living Donor Liver Team at the Center for Liver Disease and Transplantation, emphasized to me how the transplant process is an “overwhelming one.”

She also noted the role family and friends play in the process, helping to get the word out about locating appropriate live donors. It gives loved ones a way to “get back the control in this situation,” the doctor explained last Friday.

“Patients need to get through a lot of required medical testing and become experts on their disease — all while being extremely ill and carrying the emotional burden of suffering from end-stage liver disease,” Fox remarked. “Added to this is the factor of uncertainty and lack of control – when and how will I get my transplant?”

But despite world-class care and the fact that she’s won several health fights in her adult life, Gail acknowledged she is “not always optimistic.”

“There are good days, good hours, good moments and then there are the bad ones,” she conceded. “I have faced so many medical challenges where the doctors did not think I would pull through, that I am trying to treat this in the same way.”

Tough Times

There have been many health scares over the years for Gail. She took a semester off in college to have her colon and half her thyroid removed after a cancer diagnosis.

About 30 years later, the prior medical conclusion was re-diagnosed as familial adenomatous polyposis, a rare inherited cancer predisposition characterized by hundreds to thousands of precancerous colorectal polyps, guaranteeing colon cancer and/or rectum cancer at a relatively young age.

By that time, she’d developed polyps throughout her upper gastrointestinal system, which led to surgery to remove her gall bladder, duodenum, bile duct, thyroid, and part of her pancreas — all within three months.

Flash forward to today’s health crisis, Gail has been tapping into her network of contacts for help in a variety of ways.

One contact was even able to describe the process to Gail from firsthand experience.

Warren’s Angel

Three years ago, Gail’s friend’s daughter-in-law, Donna Smith, became a savior for her father Warren Graham, the type of savior Gail currently needs.

Warren, a New Rochelle native currently living in New York City, was the recipient of the medical miracle that is organ transplantation. Donna donated her liver to him in 2019.

And Warren knows he was luckier in that sense than Gail has been in her hunt for a healthy liver.

“My situation was a little unusual because once my liver doctor told me that I needed a transplant, it took about two minutes for my daughter, who was an angel, to stand up and volunteer,” the 68-year-old explained in a phone interview on Wednesday, noting he was back at work as an attorney within a matter of months of the surgery, although there have been some medical bumps in the road since. “I never would have asked for it.”

Because of the experience, he knows just how important it is for people to consider organ donation.

“It’s critical, especially when we’re talking about liver donation, because, yes, while it’s major surgery for the donor – Donna had a couple of hard days after the surgery – she was back to work within a week,” he said last week. “But you’re sacrificing for somebody you care about. It’s a little bit of a difficult time, but at the end of the day, it’s not really life-threatening, and you’re not going to lose anything because the donor’s liver regenerates.”

“Our surgeon always used to say, ‘when you donate, you’re not just saving one person, you’re saving two.’ Because then there’s one other person that is now on the donor list that can get a look.”

Lifesavers

When I spoke to Donna by phone the next morning, she posed a rhetorical question: “Unless you’re a doctor or a firefighter or a first responder in some form, when in your life are you ever going to have the opportunity to save a person’s life?”

Donna recalled joining living donor Facebook groups around the time she began the donation evaluation process.

“I was always super impressed with people who were like, ‘Oh, yeah, I want to give my liver to someone random.’ And I’m like, ‘Man, that’s like an intense surgery for someone you don’t know,’” the Queens resident commented. “But I think at the end of the day, yes, it’s 100 percent a gift for the recipient, too.”

Donna also pointed out how many people aren’t even aware of the concept of living donors. As she put it, she “always thought that all transplants were from cadavers.”

But as Donna began to learn more about the life-saving opportunity, she discovered people within her own extended orbit who’d been through the process, unbeknownst to her previously.

“And you’re not just helping one person,” she also pointed out. “Our surgeon always used to say, ‘when you donate, you’re not just saving one person, you’re saving two.’ Because then there’s one other person that is now on the donor list that can get a look. So it’s not just one life, right?”

There Oughta be a Law

Just a few months ago, on Nov. 29, Rep. Jamaal Bowman (D-Yonkers) joined 15 House representatives and U.S. senators in sending a letter to the Department of Health and Human Services, addressing systemic flaws in the country’s organ procurement and transplantation systems, including around issues of equity.

After the National Organ Transplant Act was enacted in 1984, a computerized national system for matching patients with organs was created – the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network.

The elected officials, in their November letter, cited a report that concludes the federal government could save up to $40 billion over the course of a decade with reform. They also pointed to research that shows how recovered organs often don’t get transplanted due to errors by the United Network for Organ Sharing.

“Experts estimate that 28,000 more organ transplants could take place each year if the government’s contractors were held accountable through modernizing the system and improving oversight,” the letter from the progressive representatives and senators stated. “Currently, the failure to recover more organs has resulted in greater need for dialysis and the treatment of end-stage renal disease, which account for $36 billion in Medicare costs annually.”

Bowman’s press secretary, Emma Simon, said the congressman was not available to share further perspective.

Rep. Mike Lawler (R-Pearl River), the area’s other congressman, noted through a spokesman how he cosponsored a bill in 2021 when he was an assemblyman to designate human organ delivery vehicles as authorized emergency vehicles, with emergency lights, to help ensure transplant delivery efficiency. The bill later became law.

Lawler’s deputy chief of staff, Nate Soule, while declining to provide detail, also told me there’s various federal legislation under consideration on the organ issue, and how his boss will be joining the initiative “in the coming weeks.”

It’s an issue the congressman has aimed to spotlight. Earlier this month Nanuet resident Roxanne Watson was recognized by Lawler on the House floor for signing up a record number of registrants to the New York organ donor list.

Family Matters

While bigger-picture concerns persist, the issue of organ donation is deeply personal to the Jasne family.

The monumental medical mountain they are trying to scale presents only two outcomes: life or death.

“A partial liver donation will save my life. Without it, it is a certainty that I will die,” Gail bluntly concluded. “But it is probably the biggest ask that exists. And it is not just an ask for the possible donor, but for their entire family and life. Living liver donors are incredibly special.”

As an admirer of Gail’s grit, kindness, and generosity of spirit, I sure hope those incredibly special people are reading these words right now, and at least one of them comes forward. Maybe that person is you.

GetGailALiver@gmail.com is Gail’s e-mail address if you want to reach out and possibly save a life.

Or at least send a kind word and share this piece with friends.

New Yorkers ages 16 and up can also register as organ, eye, and tissue donors. Visit Become an Organ Donor.

Adam has worked in the local news industry for the past two decades in Westchester County and the broader Hudson Valley. Read more from Adam’s author bio here.