Douglas Adams’ Kakapo and Rudolfo Anaya’s Owl

By Brian Kluepfel

Since there’s plenty of time to read these days, I came across two interesting bird-themed books last week.

Douglas Adams is best known for his “Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” series. They sold millions and earned him fame.

But in the late 1980s he traveled with naturalist Mark Carwardine on a semi-serious endeavor to observe and record some of the planet’s rarest animals, including Komodo dragons, white rhinos (not really white, it turns out) and fruit bats. The book is called “Last Chance to See,” and it’s charming, funny and alarming in turn. One of the duo’s ventures brought them to New Zealand and the endangered kakapo, the world’s only flightless parrot.

Adams admits he doesn’t like birds, yet he is charmed by the kakapo. He describes the landscapes of New Zealand with an awe often reserved for religious epiphanies. And his tracking of the kakapo, requiring a special guide and dog, is quite funny.

When Adams went to find the kakapo, there were only 40 left in the wild. There are now 209, three decades later. There is hope, even if incremental. Adams died of a heart attack in 2001 after a session at the gym, but his life, and that of hitchhikers, kakapos and hippos, are forever captured in his endearing words.

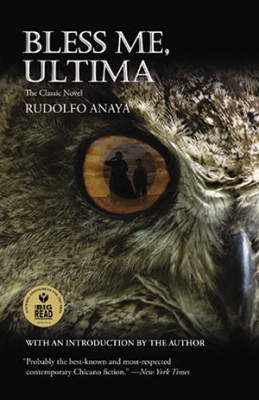

Rudolfo Anaya broke new ground with “Bless Me, Ultima” in 1972, a story revealing the author’s New Mexican roots – a mix of indigenous and Spanish-Mexican, animism and Catholicism. It’s a wonderful coming-of-age novel seen through the eyes of its protagonist, Antonio, who tries to make sense of the conflicting belief systems and world-views of his small village. The bridge, which he crosses into town each day, is as much a philosophical, as a physical, conduit.

While the people of Guadalupe conform to the norms of the Catholic church, when real crises arise, they turn to Antonio’s grandmother, Ultima, a country woman steeped in the tradition of curanderas. With Antonio, Ultima roams the hills at night, gathering herbs, revealing their healing purposes to him, bit by bit.

Antonio recognizes the presence of an owl outside the family home as Ultima’s spirit, and its gentle hooting at night brings him peace. When true problems arise among the people, which the Catholic priest’s prayers are unable to resolve, Ultima is able to bring about a just ending.

Too often in our literature and film we depict owls as omens of evil and bringers of darkness because, mostly, they live by night. Ultima’s owl is a benevolent presence, and in fact, when challenged, a protector, and in some ways shows that the two belief systems can coexist. The owl in the juniper tree outside the house is as powerful a symbol as the cross atop the church in downtown Guadalupe.

Anaya flew off with the owls into the spirit world this year. Perhaps the lesson we can take from his first novel is that there is not one correct religious vision of the world, and cultures might better coexist by building bridges, not walls.

Owl Event: In keeping with the theme of the article, the Ossining Public Library will be holding am event via Zoom about owls this Friday, Aug. 14 at 7 p.m. The discussion, presented by Stephen Sciame of Blue Campfire Experiences, covers the many evolutionary benefits of the owl in New York and include information about eyesight, hearing, camouflage and more.

The event is part of the library’s teen program. You can register at ossininglibrary.org or e-mail oplteens@wlsmail.org for info.

Brian Kluepfel is an author of the Lonely Planet travel guides and has worked across the Americas. He lives in Ossining and is proud to be a member of the Saw Mill River Audubon, and encourages you to take part in the group’s activities. Find him at www.birdmanwalking.com.