Cold Case Unraveled: Revisiting ‘Gentle Giant’ Tom Dorr Sr.’s Gruesome Murder

Opinion Advocates for ideas and draws conclusions based on the author/producer’s interpretation of facts and data.

On Anniversary of Slaying, Community Still Seeks Justice

Family Member Identifies Possible Wood Bat Hidden in Fireplace

By Adam Stone

On a haunting, snow-draped winter morning, on Jan. 8, 1996, Pleasantville Fire Department volunteers went searching for Tom Dorr Sr., their nearly 6-foot-8 friend and colleague, amidst one of the most severe storms of the 20th century.

The community’s “gentle giant,” as he was affectionately called, had gone missing the night prior, with 50 mile-per-hour winds whipping through the area and freezing temperatures catapulting emergency workers to high alert.

Dorr Sr., 50 years old and a fire department member since 1979, had answered a call from a fellow Washington Avenue firehouse volunteer on Jan. 7 to help at headquarters and stay overnight. He committed to the standby duty, prepared to help with any potential problems.

But Dorr Sr. never showed up as planned.

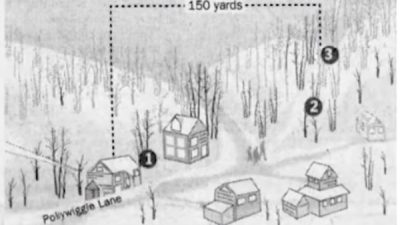

The search team arrived at the Graham Hills Park wooded area in Mount Pleasant on Jan. 8 at about 9 a.m. and started looking for Dorr Sr. along the path where he liked to feed the wild turkeys, regardless of the weather.

By about 9:45 a.m., one of the firefighters tripped over a large object. The crew then dug through a 24-inch snowbank to discover Dorr Sr.’s cold, large, lifeless body, about 150 yards from his Pollywiggle Lane home.

‘Blunt Force Trauma’

The search team found their friend viciously sliced to death, his throat slit, his head bludgeoned, his face cut up; slayings are almost always crimes of personal passion.

Other than some splattered blood on trees, and a container of bird seed, little could be collected, as much of the forensic evidence was destroyed by the historic blizzard, with about two feet of snow pounding the region.

The likelihood of a quick arrest, let alone a conviction, seemed to be melting away in the snow. Published reports say a murder weapon (probably a knife) was never located.

But I received information over the weekend to suggest a wooden baseball bat was burned in the Dorr fireplace before police searched the home on Jan. 8, 1996.

“The detective who originally investigated the case believed that one of the weapons, not necessarily the knife that was used to slash Thomas’s throat, but the baseball bat, was burned in the fireplace,” Dorr Sr.’s sister-in-law, Jane Lockett, a Jacksonville, Fla. resident, told me in a phone interview on Saturday evening.

While the baseball bat detail relies on secondhand accounts, it seems to align with the fact pattern of the crime.

The family kept a bat by the door, and they had a stove fireplace, Lockett said.

“It was cold that night and a fire was going,” she noted. “When autopsy or results of the death were found, it was discovered that Thomas likely was hit on the back of the head with a bat-like object. He was a very large man, and the speculation is that someone approached him from behind, knocked him down, likely knocked out, and then his throat was cut.”

More on that in a few minutes.

Things that Make You Go Hmmm…

A day after the body was found, the Westchester County Medical Examiner’s office completed the autopsy, ruling Dorr Sr.’s death a homicide, citing “blunt force trauma of head and chest,” according to court documents.

Authorities estimate that Dorr Sr. was slaughtered by about 6 p.m. on Jan. 7, roughly an hour after he committed to standby service at the station.

About three weeks later, on Jan. 29, the community organized a vigil at the park where Dorr Sr.’s body was found, and about 40 grieving co-workers and friends attended to pay tribute.

“I think Tommy was a gentle, giant, kind human being that everybody really loved,” Lockett said.

But Dorr Sr.’s wife and sons were not among the attendees. In fact, they have never joined mourners at the annual event, sources said.

(The couple’s only biological child, Thomas Dorr Jr., just 15 at the time of the murder, is not a suspect. Online records and sources say the 43-year-old, known as a kind, intelligent man, is now living in Duluth, Minn. More on the younger Dorr in a bit as well.)

‘Very Odd to Me’

As word spread about the horror, a general consensus emerged among people in the community about the family’s involvement in the crime. But justice has never come.

“If somebody gets killed 100 yards from your house and so viciously stabbed so many times, his throat slit, you would think people in the community would be worried about somebody in the community doing that to somebody else,” John Brooks, Dorr Sr.’s firefighter friend and vigil organizer, told me in an interview last week. “But it just seemed like everybody was in lockstep knowing that they knew who did it, and they weren’t worried about it because it was a personal family thing.”

He doesn’t mean the community doesn’t care. Just the opposite.

Brooks has been heartened by the number of people who attend the annual Graham Hills Park vigil for Dorr Sr. despite the fact that there’s only about a half-dozen volunteers remaining from 1996. (Examiner reporter Abby Luby is assigned to cover this year’s event for us on Monday night, for next week’s print paper.)

But Brooks has just been dispirited for more than a quarter-century now by the lack of accountability, despite general agreement about who killed his buddy.

“It’s almost as if everybody knew who did it, so nobody was worried, you know what I mean?” Brooks told me in our interview. “Because when somebody gets killed like that, you would think there’d be a fury, a worry that it’s going to happen again. And that part of it was very odd to me.”

‘Creepy’

In the months following the murder, the Westchester County District Attorney’s Office publicly complained about the lack of cooperation from key witnesses, noting how the refusal to help was “presenting a significant obstacle.”

By October, Crime Stoppers announced a $5,000 reward for information, but to no avail.

Police investigators ultimately went public in naming their prime suspects: Dorr Sr.’s wife, Jane Sawyer, and her son, Jeff Dorr, the product of a prior relationship who was 25 at the time of his stepfather’s murder. Dorr Sr. had adopted Jeff, who ultimately became a known heroin abuser.

Jeff Dorr’s addiction was a source of extreme tension inside the household.

In our interview, Brooks recounted the widely accepted wisdom around the village.

“Their family life was not a rosy one and their relationship was not a loving one, and the son was not a peaceful one who had drugs involved,” Brooks said. “And he hung out with the unsavory characters and heroin and all that stuff. It just wasn’t good.”

As for Jane Sawyer, a former Mount Pleasant Public Library clerk, she “was a little bit of an Addams family type,” Brooks said in our interview last week.

“She was a little creepy,” he added. “And they never really seemed like they hit it off at the fire department events. If she came, she wasn’t very warm.”

Family Matters

Jane Sawyer phoned the firehouse at about 8:30 a.m. on Jan. 8 asking for her husband.

“She asked for Tom, and we knew right away he wasn’t here,” a volunteer who was in the radio room at the time told WPIX11 in 2014.

Adding another layer of complexity to the small-town murder, Brooks said Jane Sawyer’s family was deeply rooted in the Pleasantville Fire Department.

“Her father was chief for a long time and he was a member for like 60 years,” Brooks said. “I think there’s a whole family thing that makes things weird.”

Weirder still was Jane Sawyer’s immediate reaction to Dorr Sr.’s grizzly murder.

“They lawyered up right away,” Brooks explained of Sawyer’s decision to hire an attorney on the same day her husband was found dead, shielding her and her sons from questioning. “[Jane] was looking for the life insurance money. From both his work at the White Plains Water Department and the fire department.”

The family moved to Connecticut shortly after, and Jane reportedly returned to her maiden name of Sawyer.

Mum’s the Word

When a loved one is murdered, family members obviously tend to cooperate with law enforcement not just willingly but desperately, eager to track down the killer.

“But they were quite the opposite,” Brooks said. “Like, they wanted his fire department uniform picked up, like, two days later. It was like an immediate thing. They just wanted to get rid of his stuff.”

Sawyer actually did grant an interview to the now-defunct Patent Trader community newspaper in 1996, pushing back on community outrage for her decision to keep quiet and hire an attorney instead of aiding the investigation into her husband’s gruesome murder.

“Most people get lawyers, it is not unusual, you see it on TV all the time,” Sawyer stated at the time. “I don’t know why they got angry that I did that.”

Sawyer is listed online as living in Winsted, Conn., and now 83 years old. I was unable to reach her or other suspects for comment last week.

Separately, Westchester County District Attorney Mimi Rocah’s public affairs and communications director, Jin Whang, declined comment.

You Have the Right to an Attorney

The frigid, unemotional reaction observed by Brooks and other members of the community is also a detail featured in past reporting on the cold case.

For instance, PIX11 ran a piece in 2014 where fellow volunteers recounted the family seeming unconcerned in the days after the savage slashing. They coldly summoned the department to quickly whisk Dorr’s uniform away, the reports assert.

“They did not seem terribly upset,” Larry Fasnacht, a volunteer who picked the items up, told PIX11 at the time. “They were just very anxious to get rid of the uniform. They had it all boxed up, ready to go.”

Sources also reported discomfort from other members of the Sawyer clan in 1996. Some in the group seemed uneasy with the circumstances, suggesting a possible tacit acknowledgement among relatives about the culprit, an unspoken concession about their family’s role in the tragic events.

Authorities have tried upping the reward money, increasing the total to $6,000 in 2015, between $3,500 from the Westchester County Crime Stoppers and $2,500 from the state chapter.

“We focused on the family members, the wife and the stepson,” Westchester County Police Lt. Jeff Hunt said in a Nov. 2015 NBC News report. “And right off the bat, they asked for their attorney privileges.”

Drugs

Police and fire sources also say the Dorr marriage was strained, in part because Tom Dorr Sr., after a trip to see his parents in Florida in 1995, decided he wanted to relocate to the Sunshine state, and Sawyer did not.

But Westchester County Police Capt. Christopher Calabrese, in the 2014 PIX11 piece, cited the drug issue.

“The only thing dark in that house was the use of heroin,” Calabrese said. “His stepson, Jeff…he’s an admitted heroin addict. His father would not let him use the car to go score heroin.”

Hunt, for his part, also told ABC Eyewitness News in 2015 that authorities believed the stepson “was going to New York City to buy heroin and [Dorr] denied the request to use the car.”

In the hours after Dorr Sr.’s body was found, and before Jane Sawyer secured her attorney’s services, police were able to question the family briefly, gathering some key details.

Jeff was living with Dorr Sr. and his mother at the time of the murder and wanted to take his stepfather’s four-wheel drive vehicle to New York City on Jan. 7 to score drugs, despite the weather.

Dorr Sr. initially refused, leading to an argument, but eventually relented, the family reportedly told police. (But authorities remain understandably skeptical about the notion of Dorr Sr. changing his mind about allowing his car to be used in a blizzard for an illegal drug run.)

‘Completely the Opposite’

Jeff also told police he and his mother initially joined Dorr Sr. in the historic blizzard conditions to venture up the hill, and feed the turkeys at about 5:30 p.m. that evening.

They reportedly claimed that Jane turned back, deciding not to trek to the destination, and returned to the nearby family home, a little more than a football field away.

Crucially, authorities later learned from sources that Jane and Jeff rarely, if ever, joined Dorr Sr. for his turkey feeding walks.

Why would they finally be joining their husband/stepfather, a person they both seemed to dislike (and were fighting with that day) for a one-time friendly walk amidst a generational blizzard?

When asked by police where Jeff was after Dorr Sr.’s turkey feeding, subsequent to the murder, the family’s accounts started to conflict.

After police pointed out discrepancies in their stories, that’s when authorities say Jane Sawyer decided to secure legal counsel.

“It’s very unusual,” Calabrese is quoted as saying in Westchester Magazine in 2015. “In most cases when we have a beloved family member that was murdered, the family members would bend over backward and be more than cooperative to do whatever they could do to find out who killed their family member, and, in this case, it was completely the opposite.”

Three people might have entered the woods that fateful night but only two emerged.

“We know who those two people were but the difficulty is a lack of physical evidence,” Calabrese, head of the Major Case Squad, told The Journal News.

Investigators say they ultimately learned that Jeff returned to the woods later that evening, and phoned his friend, Mike Sweet, who has also been implicated by police. They drove to the city the night of Dorr Sr.’s death, apparently on a hunt for heroin.

Authorities have previously acknowledged that they’d gathered enough proof to potentially charge crime scene evidence tampering. But they have opted not to pursue that more minor offense, according to a 2015 CBS News New York report.

“With the misdemeanor, we’ve decided not to and build a better case for the homicide,” Hunt told CBS.

County Cops

Last May, when previously poking around on this story, I spoke to Westchester County Police spokesman Kieran O’Leary.

He seemed to echo many of the sentiments about the nature of the open secret.

“I think over the years, what our people have essentially said is that there’s people in a particular family who probably know what happened, and you’re not going to get off the dime until somebody who’s given person A an alibi is going to say that they were elsewhere or whatever the deal was where they came home,” O’Leary told me during a brief phone interview.

He also corroborated the problems with evidence collection.

“Like he wasn’t discovered right away,” O’Leary said. “And then you have all that snow and everything. So it’s like as a crime scene, it was one that was not capable of being processed in the normal way, you know?”

I was still wondering if police continue to push any of the involved parties.

“So, you know, I think we’ve all but said we’re pretty sure we know who did it, but person A has got to give up person B,” O’Leary said. “And in the absence of that, the evidence really isn’t there.”

But are investigators still pressing suspects?

“I think homicides never close, so people keep investigating them,” O’Leary replied.

I contacted O’Leary about the story again last week, and requested to speak to investigators, past and/or present.

“There is no new information we can share publicly at this time,” O’Leary replied in an e-mailed statement. “This case has never been closed and remains under continued investigation.”

He also said current detective supervisors “want to leave it there at this time.”

Ex-Fire Chief

I also connected last week with Tony Rufino, an immediate ex-fire chief in Pleasantville at the time of Dorr Sr.’s murder who left the area for South Carolina about a dozen years ago.

“Tom was just a nice guy,” the former chief said. “You needed something done in the firehouse, Tom was always there. I served as chief in the early ‘90s. And when I needed something done, I’d give Tom a call. He would always be there.”

Following up on Brooks’ reference to Jane Sawyer’s family’s connection to the fire department (her father, Dwight Sr., was a longtime chief, and her brother, Dwight Jr. also served as a volunteer), I asked Rufino how that dynamic impacted the aftermath.

“Well, the Sawyer family, they were fire department,” he replied. “The father Dwight Sr. was in the department. Dwight Jr. was in the department. Tom was married in. Tom was in the know. He came in and, you know, he was accepted. Like I say, great guy. Don’t forget, it was a small village. Everybody knows everybody.”

I asked Rufino what people in Pleasantville at the time believed to be the motive.

“What could a motive be? The rumor tied all these people together,” he replied. “But what’s the motive for murder? Love or money.”

Money, Money, Money?

In August, retired police detective and licensed private eye Derrick Levasseur, a popular podcaster, prepared a comprehensive 38-minute video, investigating Dorr Sr.’s murder. The segment has already garnered more than 44,000 views.

The primary motive in this case has remained relatively murky, or at least debatable. But beyond the drug issue, possible evidence surfaced early in the investigation about a financial incentive, Levasseur observed.

For instance, 18 days after Dorr Sr. was murdered, Sawyer filed for her late husband’s $105,000 life insurance policy, equivalent to about $200,000 today.

At the time, her lawyer, in a Mar. 6, 1996, letter, asked police for confirmation in writing about the fact that Sawyer wasn’t charged with her husband’s murder, so she could collect on the policy.

In response, police acknowledged Sawyer had not been charged, but emphasized her status as a suspect, her refusal to cooperate and her blocking of questioning of her sons, including “her juvenile son, of which she has legal control.”

“If your client and her family care to cooperate and freely discuss the circumstances leading to Mr. Dorr’s death, I will be in a position to honor your request or deny it, as the case may be,” reads a portion of a detective’s cleverly-crafted response to Sawyer’s lawyer.

In other words, shove off.

‘She’s a Victim as Well’

Sawyer was initially denied the money, based partially on the detective’s letter, but she later collected the cash on appeal, after the insurance company was ordered to fulfill the policy.

In a separate financial connection, just two days after Dorr Sr.’s murder, police say Sawyer contacted the White Plains Water Department where her late husband worked, to inquire about $70,000 in benefits.

Court documents show how Sawyer waited less than two months to officially file for the benefits but because she was already a police suspect, her application was denied.

Her lawyer later told The Journal News how when homicides occur, the last people to see someone alive and family members just automatically become potential suspects by default. Being a suspect, the attorney pointed out, isn’t inherently suspicious.

“I would just remind people she’s a victim as well,” the lawyer said to the newspaper.

Sawyer pressed forward for at least five years in her quest to collect the water department benefits, attending a mid-January 2001 appeals hearing about her eligibility. The proceedings included testimony from a detective who confirmed how the widow remained a suspect.

“The only way we would rule out [Jane Sawyer] is if we had evidence someone else committed this crime without her assistance,” the detective testified, hinting at Sawyer’s possible knowledge about the crime, but not necessarily advance information or participation in the actual act of killing Dorr Sr.

Levasseur interpreted this particular detective testimony to be a barely coded olive branch from police, seeking Sawyer’s potential cooperation.

But Sawyer’s appeal to collect on the $70,000 in death benefits was denied.

‘Small Window of Opportunity’

Levasseur also raised an important point when framing the extreme unlikelihood of a random attack, citing the timing and location of the murder.

“This incident where Tom was found, where his body was located, was only about 150 yards from his home, and only about an hour after he got the call,” the experienced investigator said, referring to the 5 p.m. call Dorr received about standby duty and the estimated 6 p.m. time of his murder. “He was still alive at that point. And that’s not a big distance, and that’s not a big window.”

In the middle of a blizzard, few people were outside.

“Small window of opportunity where he could have been attacked and not far from his home,” Levasseur said. “And there were other houses in the area. So you would think at that time, if there was an attack, you might have heard something.”

Based on the stormy conditions, there wasn’t likely anyone else in those woods, and it would be a spectacularly odd set of circumstances for a random mugging, followed by a rage-filled slicing and dicing of an unknown victim.

A robbery would have likely led to a fight, and Dorr Sr.’s injuries did not suggest a struggle where the giant man saw danger looming.

Did the assailant surreptitiously hit Dorr Sr. over the head with a baseball bat from behind, stab him, alter the scene, and then let the firefighter bleed out?

“It’s hard to believe that in that short window of time, that small geographical location, that these two individuals that were with the victim wouldn’t have seen or heard something if Tom had been attacked by another party,” Levasseur said in his podcast.

At the end of the episode, Levasseur presents two theories of the case, one where Jane knew the murder was about to happen, but one where she did not. Maybe she was just a mother who felt compelled to protect a guilty son?

Under that second scenario, Levasseur describes a situation where Jane genuinely couldn’t make it up the hill, and was escorted home by her son, who then dropped his mother off at home, and returned to attack Dorr Sr.

“He says, ‘Hey, I’m going to go back up, I want to hang out with Tom,’ goes back up the hill, kills Tom, alters the crime scene, and then goes back to the house,” Levasseur speculated. “And Jane doesn’t know anything.”

NCIS: Cold Case Unit

Late last week I was also able to reach South Carolina’s Joe Kennedy, heralded as a living legend within the world of unsolved murders.

He spent 28 years at the Naval Criminal Investigative Service, better known as NCIS. If you don’t already know from the TV shows, NCIS is a federal law enforcement agency responsible for investigating felony crimes, combatting terrorism and protecting military secrets.

Remarkably, Kennedy started and pioneered the NCIS cold case unit. He mentors young detectives across the country.

In 2016, Kennedy founded the Carolinas Cold Case Coalition, a nonprofit, volunteer-based organization comprised of retired local, state and federal law enforcement officers. Kennedy and other seasoned investigators dispatch entirely free counsel to police departments looking to crack tough cases.

Investigators must reach out to the coalition unprompted if they want the organization’s help.

Upon my suggestion, Kennedy watched Levasseur’s podcast about Dorr Sr. after I requested an interview last week.

In our phone conversation, Kennedy said that only about 15 percent of cases are resolved through physical evidence, and just 35 percent with witnesses. Half the time a prosecution features a confession.

“Isn’t that crazy?” commented Kennedy, a former special agent in charge of the Carolina field office.

He acknowledged the Dorr Sr. case is a tough nut to crack. But while an aging case comes with many disadvantages – witnesses die, recollection of events gets foggy – the passing of time can actually be an investigators’ friend.

“And,” Kennedy noted, “in this particular case, there’s a couple of things I would be really interested in.”

‘A Coping Mechanism’

Kennedy said investigators should contact Dorr Sr.’s biological son, Thomas Dorr Jr., who was just 15 at the time of his father’s murder, to ask what family whispers he might have overheard as a teen and throughout the decades.

“I think it would be one of the things we would be interested in as to what he’s been told all these years,” Kennedy said.

He also suggested that investigators research any relationships Jeff Dorr and Jane Sawyer might have forged in the years following the murder, and interview those sources.

“In the vast majority of cold cases, the suspects always tell somebody they did it,” Kennedy explained. “Here’s how it normally unfolds. They’re out at the picnic table drinking, and it seems like they’re bragging. They say, ‘Oh, yeah, I did this.’ It’s a coping mechanism to get it off their shoulders. But the people who they’re confessing to don’t believe them because they’re drunk.”

He also said the act of committing a murder “sometimes shifts people into being a better citizen.”

“They find religion, they become a productive citizen,” Kennedy said. “So I would be very interested in looking at the lives of all of the players, not just the wife and the older son, but anybody else that was around.”

Further review about the nature of wounds in a murder case can also prove helpful.

“Let’s say all the stab wounds are on the right side of the victim’s body,” Kennedy said. “Then maybe we’ve got a left-handed killer.”

Loose Lips

Kennedy did cast doubt on the notion of the murder being premeditated for financial reasons, estimating that only 3.5 percent of homicides are pre-planned.

“And when you look at the amount of life insurance, to me, that’s not an inordinate amount of money,” Kennedy said.

Most killers are triggered in the heat of a rage-fueled moment, he stressed.

“I think it’s probably like a lot of murders, some kind of altercation [over] this thing or [a] disagreement that went bad and it could be over heroin, his heroin usage,” said Kennedy, who published a book with a co-author in March titled “Solving Cold Cases: Investigation Techniques and Protocol.” (There are about 300,000 U.S. cold cases dating back to the late 1960s.)

He advocated for revisiting the case from the beginning, analyzing the lives of all involved parties after the murder, and, again, exploring potential confessions that suspects may have made over the years in loose-lipped moments.

“We’ve got to go back,” he said. “Who all lived on that road back then? Who has been in her life or the older son’s life? Who have they told? Here’s the thing: They always tell somebody.”

I asked Kennedy whether he thought authorities should bring charges on potential evidence tampering, if they can’t make a homicide case.

“Well, you’re not going to bring resolution to the murder,” he replied. “I’ve got issues with it being tampering because I don’t think the evidence has any probative value. That’s what a district attorney is looking for, evidence that has probative value.”

Human Story

It’s critical when covering these types of stories to remember you’re dealing with real people, not fictional characters in a crime novel. The reverberations of Dorr Sr.’s murder still complicates the lives of his family members and others to this day.

I spoke by phone on Saturday afternoon with Steven Dorr, the older brother of the late Tom Dorr Sr. He’s 81-years-old, and lives in a senior living facility in Jacksonville.

I learned he now suffers from dementia. But he was able to communicate some basic thoughts, confirming his brother’s precise height and other key facts of the case.

It was heartbreaking to hear how he’s basically given up hope when I asked if justice might eventually prevail.

“It seems doubtful after all these years,” he replied.

But after the call, I phoned his wife, Jane Lockett, Dorr Sr.’s aforementioned sister-in-law.

Unique Perspective

A volunteer at the Mayo Clinic, the 77-year-old retired IBM Global Services executive revealed a deep well of knowledge about the case, and shared new insights. She has not given up hope.

“His family obviously were all very affected by what happened,” Lockett said.

Her husband Steven Dorr, a former electrical engineer boasting a 175 genius IQ before dementia and a Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute graduate, kept extensive files on the case. Lockett recently shared the documents with Thomas Dorr Jr., her nephew through marriage.

For many years, Steven Dorr maintained a positive relationship with his nephew, Thomas Dorr the younger, and a cordial one with Jane Sawyer. Lockett and Steven Dorr even joined Sawyer on a road trip to Connecticut decades ago when Thomas Dorr Jr. was in college.

“Obviously,” Lockett noted, “with Steve’s increasing dementia and reduction in communications skills, he has said or done something to damage his relationship with Thomas.”

Manila Folder

Although she married Steven, her second husband, in the years after the murder, she’s learned a mountain of relevant detail about the crime’s circumstances from the family over the years.

“So I’m just kind of a conduit because I’m still around, and I do stay in touch with Steve’s nephew, Thomas Dorr, who’s his only living blood relative at this stage of the game,” Lockett explained.

She grew especially fond of Anna Graf Dorr, her mother-in-law, Dorr Sr. and Steven Dorr’s late mother.

Graf Dorr moved to Florida in her later years. Lockett and her mother-in-law would buy wool to knit mittens for needy Native American children out west. And they would also chat.

Lockett learned that Graf Dorr and her husband, Hermann Dorr, “were very suspicious that the one son, Jeff, was wanting money and Tommy wasn’t going to give him any more money.”

What more exactly did Dorr Sr.’s late parents believe about the homicide?

“There was some argument and that the mother helped in covering up the murder,” Lockett said.

And does Thomas Dorr Jr. now possess all the files Steven Dorr meticulously curated through the years?

“Steve had a manila file folder full of clippings that he’s kept from the death to today,” Lockett said. “I’ve been going through these things and I’ve been sending them to Thomas, everything I possibly can that is related.”

Only about two months ago, the documents were delivered by mail to Thomas Dorr Jr. in Duluth, Minn., and Lockett confirmed that her nephew was provided, unsolicited, with “all relevant Dorr family files.”

Baseball Bat

Lockett said the files she mailed to her nephew include references to the alleged baseball bat used to bash his father’s head, before he was knifed to death.

When investigators entered the Dorr family home for questioning on Jan. 8, 1996, Lockett said they might have discovered pieces of the bat within the fireplace, an assertion I’d never personally heard before our Saturday interview.

“They interviewed the family, and apparently they kept a baseball bat somewhere in the house,” Lockett said. “Remnants of a wood baseball bat in ashes in the fireplace that hadn’t been completely burned. You know how chunks of wood sometimes get left over.”

Thomas Dorr Jr., to survive childhood, remained close to his mother in the aftermath of his father’s murder, Lockett sympathetically noted, pointing out how mother and son shared a joint love of animals.

But when Jane Sawyer ultimately passes away, does Lockett believe her nephew will reveal what he knows to authorities?

“Yes,” Lockett replied, “yes, I do.”

Gray Day

In fact, Lockett made a point of emphasizing how Thomas Dorr Jr. is not “particularly close to his step brothers at all.”

(She identified a second son of Sawyer’s from a prior relationship who I hadn’t heard about before our interview.)

Lockett described Thomas Dorr Jr. as a “gifted, kind, gentle young man” who “represents to me the best of Anna Graf Dorr, who was an amazing, patient and kind woman.” She also said he’s someone who “doesn’t suffer fools gladly.”

Despite his affection for his mother (Jane Sawyer still “likes” some of Thomas’ social media posts, according to Lockett) she stressed how her nephew knows “life isn’t just black and white, that there are shades of gray, and you can live with those shades of gray.”

An information technology officer at a university, Thomas Dorr Jr. is married to a Ph.D. and college professor in Minnesota who teaches philosophy. He did not reply over the weekend to my request for an interview.

Justice for All

The way Lockett understands the series of events, the younger Thomas Dorr basically barricaded himself in his room on the night of the turmoil, ducking for cover with tension enveloping his angst-ridden household.

“Before Tommy walked to the fire department to volunteer that terrible snowstorm, something happened within the family that caused Thomas to stay in his room and not want to participate in anything with the family,” Lockett said.

In the years leading up to the murder, the dynamics within the Dorr home were terribly troubled, Lockett said she’s been told, with Dorr Sr. and Sawyer likely heading to divorce.

Lockett and her husband, Steven, along with her husband’s mother and other members of the family, believe Jeff acted alone, without Jane’s advanced knowledge.

A mother of two adult daughters herself from a prior marriage, Lockett said she’s wrestled with the ethical questions her sister-in-law Jane Sawyer allegedly still confronts.

“I ask myself every day out of love for my daughters would I make the same choice,” she said. But, Lockett concludes, she “would not do anything to protect them if they broke the law. I would make sure that they were raised to face up to justice.”

Money was also tight at home, she said.

“You know, there was life insurance, and the son understood that if Tommy dies, mom gets life insurance, we get money,” Lockett said. “That solves some of our financial issues.”

Lastly, I wanted to better understand the nature of the ongoing police investigation over the years.

Lockett confirmed that “for many years the original detective reached out to Steve and talked with him annually and checked in with Steve to let him know if there was any progress.”

But Steven Dorr’s cognitive impairment began in 2014, and the original detective has since died, Lockett said.

Your Witness

When we started The Examiner in 2007, more than a decade had already passed since Dorr Sr.’s murder. Since then, we’ve covered the annual vigil most every year, and this week is no exception.

To state the obvious, the notion of criminal accountability for murder in civilized society predates the existence of forensic evidence by many millennia.

But without witnesses or a confession, authorities just haven’t been able to muster probable cause and make an arrest. Yet I do still wonder whether a narrow lane exists for the criminal justice system to take a credible crack at a case.

Could expert testimony be used? Untapped financial records?

Might advances in forensic technology allow investigators to retest samples currently tucked away in a police locker to unearth new evidence? In 2020, Kansas City cops used genealogical DNA testing, via federal resources, to solve a 31-year-old murder, identifying victim Fawn Cox’s late cousin as a suspect.

(However, forensic relevance in this case is also complicated by the fact that the suspects’ presence at the scene doesn’t prove anything by itself.)

Or, as Kennedy suggested, can detectives interview new sources and/or family who might have been on the receiving end of barstool confessions or childhood murmurs?

Would the process of arresting multiple parties by its very nature help secure prosecutors with a cooperating witness?

Could the threat of a lesser charge be brought during questioning to gain testimony?

Maybe, but certainly maybe not.

Authorities, in my view, should either redouble efforts to investigate new witnesses or bring what they can bring.

Don’t misunderstand: Ramping up the probe – if it’s not already ramped – would obviously be immeasurably superior to making minor, potentially inconsequential arrests.

Closing Arguments

Speaking as a layman, not a legal expert, the circumstantial evidence strikes me as potentially sufficient to persuade a jury about culpability, beyond a reasonable doubt, even if many miles from a slam dunk. Thinner cases have certainly been made and won.

As for the potency of circumstantial evidence, it can theoretically be used as the primary tool to build a case.

For instance, to cite a famous example, Scott Peterson was convicted in the murder of his pregnant wife, Laci Peterson, in 2004, with the prosecution relying largely on inconsistent alibis, suspicious behavior and witness testimony to craft a cohesive, convincing narrative despite limited physical evidence.

But if no charges of any kind can be made on the people who authorities believe committed the crime and/or engaged in the cover-up, the community will always be left nursing a gaping, unhealable wound.

Can a credible argument be made that the District Attorney’s Office confronts more pressing public safety priorities than pursuing a nearly three-decade old case? Of course.

However, in my view, that line of logic is unambiguously trumped by a far more important principle: You can’t kill someone or conceal a crime in this community and avoid charges with impunity, no matter how much time has passed.

It’s an especially important message to send loud and clear in Pleasantville. Just a decade ago, in 2014, 76-year-old resident Linda Misek-Falkoff was stabbed to death, found dead in her home at 79 Grandview Ave. With no witnesses, Westchester County police detectives haven’t yet been able to file charges.

But, in the Dorr Sr. case, authorities say they have their suspects. And they have evidence.

It’s simply never too late for real justice.

Adam Stone is the publisher of Examiner Media. Email him with tips and feedback at astone@theexaminernews.com.

Adam has worked in the local news industry for the past two decades in Westchester County and the broader Hudson Valley. Read more from Adam’s author bio here.