CareMount/Optum Patient Details Disturbing Saga of Cologuard Test Kits

Opinion Advocates for ideas and draws conclusions based on the author/producer’s interpretation of facts and data.

SPECIAL INVESTIGATION

PRIVACY BREACH

CareMount/Optum Patient Details Disturbing Saga of Cologuard Test Kits

- Patient Data Exposed: Understanding How Optum Compromises Privacy

- The Fallout: Legal Ramifications and the Urgent Need for Accountability

- Deceptive Marketing or Genuine Oversight? Examining the Tactics at Play

- Regulatory Scrutiny: Is Optum’s Approach Breaking the Law or Just Skirting Medical Ethics?

- Alleged ‘Double Billing’ and ‘Fraud’ Concerns: Peeling Back the Layers on Patient Impact

This is the ninth installment in an investigative series about

By Adam Stone

Given the dizzying pace of recent change, it can be hard to process – or even sometimes identify – what aspects of cold corporate sick care are already part of a disturbing American normal and what offenses are new to the increasingly amoral and massive medical industry.

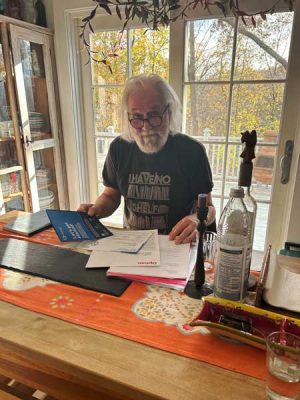

That dynamic struck me when interviewing Mount Kisco’s Michael Kleff, who received unsolicited testing kits at his doorstep this summer followed by an avalanche of insistent messages urging him to take the tests all while never having asked for them and not having shared his private information.

For Kleff, a 71-year-old retired German journalist, the medical marketing push, disguised as medicine, has become his unsettling healthcare reality, emblematic of a much broader U.S. trend.

He described the chain of events to me during an interview at his home last Wednesday. Kleff contacted me after having read an earlier installment in this series about CareMount/Optum’s highly-questionable billing practices.

While in Germany this past summer, the longtime CareMount patient was sent a Cologuard colon cancer test kit package on July 17 from the Madison, Wisc.-headquartered Exact Sciences Laboratories, a molecular diagnostics company specializing in early stage cancer detection.

Subsequent letters and messages from Exact Sciences and Optum were sent to Kleff and his wife, Nora Guthrie, who had also received a kit. (Guthrie, president of The Woody Guthrie Foundation, is the daughter of the late, legendary singer-songwriter Woody Guthrie.)

“Neither my wife nor I had requested Cologuard,” Kleff said. “And also, our family doctor confirmed on inquiry that he had not arranged to have Cologuard to be sent to us.”

Money, Money, Money… Money

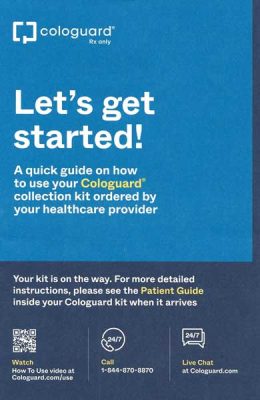

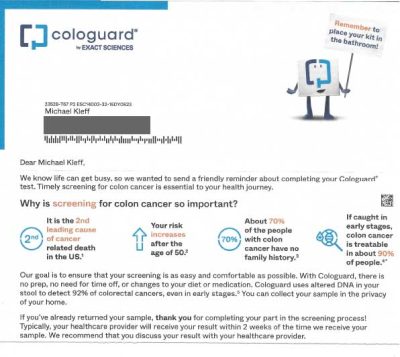

A letter from Exact Sciences Laboratories (the owner of Cologuard) pushed hard for Kleff and Guthrie to complete the at-home test, framing it as a “friendly reminder.”

“Timely screening for colon cancer is essential to your heath journey,” a note warned.

In one of multiple letters the couple received this summer, Optum acknowledged how the company was “working with Exact Sciences to send you an at-home colon cancer screening test” while also pointing out how Cologuard is “covered by Medicare and most major health plans.”

Cha’ching.

“It’s an example how profit-geared the healthcare system is here because the second I send this back, then they will charge my health insurance that I did it,” Kleff said. “So there is a major money aspect in this.”

He then motioned to the material on his kitchen table.

“As long as it’s sitting here,” Kleff added, “they can’t charge my health insurance because I haven’t used it.”

In fact, making the data breach even more egregious, there is zero medical justification for urging (let alone endlessly harassing) Kleff and Guthrie to take the test given the fact that they’d both had colonoscopies in Germany (where they live half the year) during the summer of 2022.

Welcome Home

After the colonoscopies last year, upon returning to the United States, they informed their local CareMount doctor at an annual physical this past March that they had already undergone these screenings.

“And the doctor said, ‘I’ll see you in five years,’” Guthrie told me when I visited the couple. “I talked about this with my regular primary healthcare physician. So that’s why it was particularly surprising when we got all of these requests for a colonoscopy test.”

A letter emblazoned with the Optum logo told Kleff “we believe you may be due for a cancer screening.”

That’s untrue – the company had no reason to “believe” that.

Kleff and Guthrie had returned the first week of last month from a four-month stay in Germany and discovered a flurry of messages on their answering machine regarding the unsolicited Cologuard test kits. The campaign of follow-up calls has continued unabated.

“And I would say at least 25 were either Optum or the lab kind of reminding us that we received the Cologuard test kit and we should get back to them and blah, blah, blah,” Kleff said in a phone interview last Tuesday before we met in person.

Concerned about the source of these unsolicited test kits, Kleff reached out to his doctor, who confirmed that he had not arranged for the Cologuard kits to be sent and knew nothing about them.

It raises the pressing question of how Optum could ethically (or perhaps even legally) justify the apparent sharing of Kleff and Guthrie’s personal information, such as names, address and phone number, with a private company without explicit patient consent.

“I mean, being a German citizen, I know how the healthcare system works in Germany, where it is not for profit,” Kleff said. “This, for me, again, is a good example of the healthcare system in this country, which is for profit, not for the patient. Everything is for profit, every step along the way. And even Obamacare didn’t change that. It brought more people in the system to buy healthcare, but it’s still for-profit 100 percent.”

‘Breach of Privacy’

Kleff decided to take action on the couple’s (and society’s) behalf and wrote a letter to Optum President Heather Cianfrocco, seeking an explanation for the apparent unauthorized sharing of personal data.

“We spoke to our primary care physician who assured us that he had not ordered Cologuard,” Kleff wrote in an Oct. 18 letter last month, sent to Optum’s Eden Prairie, Minn. headquarters. “Now we are wondering how Optum comes to give our health and contact information to a private company without our knowledge and consent. We consider this a breach of privacy regulations.”

Kleff hasn’t received a reply yet from Cianfrocco, who was named Optum president about three months ago. He sent her a reminder note last Wednesday afternoon after our in-person interview.

However, about a week after having sent the Oct. 18 complaint, Kleff did field an unprompted phone call from an employee of Riverside Medical Group, representing Optum. (CareMount, Riverside and ProHEALTH are all now part of Optum Medical Care.)

This employee proved quite helpful, initiating inquiries with all the doctors Kleff had been in contact with over the years. Every single one of them confirmed they had absolutely no involvement in sending the Cologuard kits.

The representative, according to Kleff, then provided confirmation that personnel within the company had initiated the process to send Cologuard test kits to a specific demographic.

Optum, it turned out, had indeed arranged for the Cologuard test kits to be shipped, Kleff said he was told.

“Her words were that ‘Someone within Optum has started this to have the Cologuard test kit sent to a certain population,’ whatever that means, I guess 55 years old and older,” Kleff said. (Cologuard markets to patients 45 years and older.)

But Kleff noticed on Wednesday that a guide accompanying the kit corroborated what he already knew; it said the test was “ordered by your healthcare provider.” (We’ll set aside the fact that a marketing initiative shouldn’t be synonymous with the notion of your “healthcare provider.”)

Paging Dr. Acme Corporation

In a separate and subsequent phone call, a manager of “Optum Patient Engagement” called Kleff and tried to explain the purpose of the Cologuard tests. But Kleff wasn’t going to let the legally savvy corporation off the hook with a fleeting, undocumented phone call, let alone a nonsensical one.

“I made it clear to her,” Kleff told me, “that my complaint was not about that, but about the breach of privacy regulations. And I also made it clear to her that I was insisting on a written response from corporate at Optum.”

Kleff stressed how only a doctor should be encouraging him to get tested.

“I have a personal relationship with a doctor, he or she should be the one to advise me regarding my health, not someone within a corporation who thinks, ‘Oh, that’s a great idea, let’s send them all these things,’” Kleff said.

While test kits might seem innocuous, even helpful, the potential compromise of data through the sharing of information with external companies raises real concerns about unauthorized access, let alone concerns about dispatching “medical advice” through a marketing department.

Each additional entity involved in processing data introduces more points of vulnerability, increasing the likelihood of security lapses and unintended disclosures.

Shipment Label

In the first half of 2023, the healthcare sector experienced about 295 breaches, as reported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)/Office for Civil Rights (OCR) data breach portal, impacting more than 39 million people, according to Fierce Healthcare, an industry publication.

HCA Healthcare, a publicly traded U.S. healthcare operator, reported a data security incident in July where patient information was accessed and made available online “by an unknown and unauthorized party.”

“While our investigation is ongoing, the company has not identified evidence of any malicious activity on HCA Healthcare networks or systems related to this incident,” the company reassured patients at the time in a July 10 statement.

Even if a provider, in a scenario like with the Cologuard shipments, executed on logistics without sharing data, concerns persist about recipients mistaking marketing for medical advice, which erodes trust and highlights the ramifications of blurred boundaries between healthcare and promotion.

Caveats aside, the packages sent to Kleff and Guthrie – and presumably a disturbing volume of others – were delivered with a return address from Exact Sciences in Wisconsin.

“I think the most important factor is the shipment label,” Kleff said in a follow-up phone interview last Friday morning, referring to just one piece of compelling circumstantial evidence that his data was shared without his specific consent.

He also pointed out how “some of the calls were from Exact Sciences.” Kleff did acknowledge how he’s not 100 percent certain of his recollection that a portion of the phone messages were from Exact Sciences/Cologuard, as opposed to all from Optum, because he deleted voicemails in frustration.

But he’s next to positive.

“If I would be less cautious, I would say I’m sure,” he clarified.

Just Checking! (Again)

During my visit to their home last week, the couple played their answering machine, including a message Optum left for them last Monday, which they did save.

An Optum Care staffer, who said she was calling from New Jersey, didn’t even leave a return phone number.

It was about the 25th message the couple has received since the summer. (Optum is a subsidiary of insurance industry heavyweight UnitedHealth Group, a stunning conflict of interest in plain sight, mixing medical care with insurance billing incentives inside the same multinational corporation.)

“This call is to inquire if you received your Cologuard kit,” the Optum representative from New Jersey said in the voicemail message, asking yet again whether Guthrie, 73, had taken the test yet.

Optum is growing robustly, as it boasts a staggering 100 million-plus consumers across all 50 states, serving other healthcare organizations and individual patients while employing 165,000 people worldwide. There are about 70,000 Optum-aligned physicians across more than 2,000 locations.

Just six months ago, the mammoth company (which exceeded $100 billion in annual revenue in 2018) proposed an unsolicited cash offer exceeding $3 billion to acquire a home health provider, Amedisys.

UnitedHealth Group launched Optum in 2011, and it currently encompasses three distinct divisions: Optum Health, focusing on health services; Optum Insight, providing data analytics and research solutions; and Optum Rx, specializing in pharmacy care services.

It’s a frightening healthcare-related trifecta of supremacy from the world’s most dominant player in the insurance market.

CareMount/Optum/United no longer replies to my requests for comment.

Selling Widgets

I asked Guthrie for her take on healthcare organizations operating like they are any other corporate retailer, as if they’re selling morally neutral products and services outside the framework of medical ethics.

She pointed to the expanding effort to capture business from aging baby boomers. People such as her and her husband.

“And I wouldn’t be surprised if the next time we receive free drugs in the mail saying, ‘You might have a heart condition, you should take this,’” said Guthrie, a longtime local resident whose children went through the Chappaqua School District.

Guthrie also expressed concerns about the intrusive techniques used in medical commercials targeting seniors.

As for the Cologuard TV marketing blitz specifically, the humorous spots have become something of a pop culture phenomenon. Their omnipresence even earned them a spoof on Saturday Night Live in a February fake commercial starring guest host Woody Harrelson.

But in the real commercial spots, actors emphasize how the product comes as a result of a physician’s recommendation, whereas Kleff and Guthrie’s doctors played no part in endorsing the deliveries.

“My doc wrote me the script, box came by mail, showed up on Friday,” a handsome middle-aged man walking a dog in the park sings in the jingle as a digitally illustrated and personified box of Cologuard with feet struts by his side cheerfully.

Vulture Marketing

And here’s the thing: When a box comes by mail accompanied by your healthcare provider’s imprimatur, followed by persistent letters and calls, people often and more than understandably assume they’re being provided with medical advice, as opposed to receiving marketing material.

“It (falsely) appears like it’s coming from your medical practitioner out of care and love for you,” Guthrie said, adding how “when you look at who’s getting scammed the most, it’s senior citizens.”

Also, as Guthrie pointed out, we’re all footing the bill at the end of the day.

“So tax money goes to pay Medicare to pay Cologuard for the test,” she said. “That’s one more thing that they can put on their list of charges for Medicare to pay them.”

The increasingly forceful medical marketing campaigns aren’t reserved to Cologuard.

Only a month ago, on Oct. 16, Optum unleashed a mass e-mail to patients, notifying many, in part: “You have pending lab work, and an appointment is not required. Lab work may include blood draws, specimen collection, EKGs and pre-surgical testing, including COVID testing.”

A local resident took to the Nextdoor social media platform to voice her displeasure.

“Optum is issuing this email to all patients (without specific details) to encourage them to undergo bloodwork for Hepatitis C screening,” the resident rightly complained.

A source shared a similar email with me they received just this past Saturday night: “You have open lab work due,” Optum wrote, characterizing it as one of the provider’s “essential reminders.”

But the source did not have any lab work due.

The e-mail marketing, in particular, preys on older people who aren’t tech savvy.

“It’s all geared towards senior citizens who don’t understand a lot of the intricacies of the internet and links and all that,” Guthrie observed.

That’s Private

I asked Kleff about potential next steps, and whether he’s exploring accountability. He said he “can’t tell” yet whether there’s a legal component but he’s eagerly awaiting Optum’s written reply.

“Well, I would like to check if there’s a legal element in this with the breach of private data,” he said in our first phone interview. “I started reading the privacy paragraphs of Optum and it was so many pages that at some point I gave up. It’s what they can do and what they can’t do. So I really didn’t look into detail.”

I did review Optum’s privacy policy, where the company claims to be committed to safeguarding personal information and complying with applicable privacy rules and regulations.

The policy says the company may share personal information with third-party companies they collaborate with or hire to perform services, such as e-mail management and website hosting.

Among the legalese is the following self-serving proviso: “We will only share your personal information with third parties as outlined in this policy and as otherwise permitted by law.”

That “otherwise permitted by law” turn of phrase, presumably constructed by savvy attorneys, sounds unsurprisingly like a policy designed to stretch the legal envelope as far and wide as possible.

Amoral Medical Industry Universe

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) is a federal law that sets standards for the security and privacy of patients’ protected health information (PHI).

It requires healthcare providers and organizations to implement safeguards to protect patient data.

Did Optum potentially breach HIPAA’s privacy rule by sharing Kleff’s personal information without consent, failing to ensure what’s known as the minimum necessary safeguarding of protected health information (PHI)?

I posed that question to the Office for Civil Rights, which operates under the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Penalties for HIPAA violations are typically enforced by OCR.

However, OCR’s press office did not reply to my phone and e-mail requests last week for more information, including messages I sent asking how the office typically handles potential violations in healthcare organizations and the steps required for ensuring patient data security.

“Well, it’s definitely unethical,” Kleff said.

Yes, You

That’s the central point, beyond any potentially murky legal areas. Not too long ago, up through the 1990s, we largely lived in a world of solo practitioners and small medical groups.

Our defenses, in this way, didn’t need to be up so warily when consuming healthcare, even just a quarter-century ago.

A handful of medical industry corporations are now tightening their grip on our care, which would be more accurately described as “sick care” rather than healthcare, as currently practiced for mind-melting levels of profit.

People like you – yes, you – need to lobby your elected representatives to protect patients from privacy breaches, unethical medical marketing and the surging growth of already massive monopolies.

That’s the best hope we have to avoid slipping even deeper into this corporatized medical abyss. And yes, it can get a lot worse.

Current healthcare industry policy isn’t some static, enduring abstraction written in stone. We shouldn’t accept the status quo as fated for the future.

Context

The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) – along with the states of New York and Minnesota – voluntarily dropped their legal challenge against the $13 billion (and controversial) merger of UnitedHealth Group and Change Healthcare, in March, with the government recognizing the uphill battle.

The DOJ had unsuccessfully argued that the merger would allow UnitedHealth to gain access to trade secrets from insurance industry competitors. Change Healthcare is a company that helps simplify healthcare financial processes.

But in July, new reports emerged about a separate DOJ monopoly investigation into major healthcare players, including UnitedHealth and CVS Health, focusing on potential antitrust concerns, mirroring previous inquiries by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in related sectors.

Also, just last month, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that lots of direct-to-consumer advertising of medical devices, including blood pressure monitors and contact lenses, engaged in false advertising, targeted vulnerable groups and led to increased demand and higher costs.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the FTC share responsibility for overseeing such advertising, taking a combined 300-plus enforcement actions from 2018 through last year.

“Advertising can negatively affect the patient-physician relationship by interfering with the ability to arrive at the best treatment option,” a pair of stakeholder groups interviewed by the GAO concluded, as described by the GAO.

Mumbo Jumbo

On Nov. 4, an e-mail from Optum Tri-State CEO Kevin Conroy appeared in Kleff’s inbox, and he initially wondered whether it might be the substantive reply he had been awaiting.

“On behalf of the Optum Medical Care team, please accept my appreciation for the opportunity to care for you and your family,” the non sequitur form letter from Conroy absurdly stated. “Trusting us to care for you and your family is a privilege, and that’s something all of us at Optum never take for granted.”

Cringey corporate mumbo jumbo aside, Kleff has also dealt with the type of infuriating billing problems I’ve documented in the most recent installments of this series.

Over the past 11 months, this investigative series has uncovered and reported on a variety of issues: questionable COVID-19

I’ve also covered the issue of doctor shortages at Optum, and highlighted the associated medical risks for patients. Sources have shared several recent accounts of their Optum doctors escaping the firm.

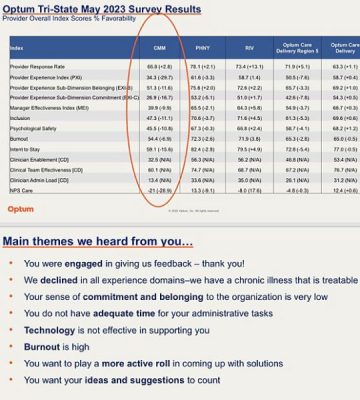

Conroy, for his part, expressed a commitment in a February 20 letter to address concerns by adding physicians, expanding the call center, and forming a patient advisory council. He said the organization would be “increasing the number of physicians and advanced practice clinicians on our care team to provide you with additional opportunities to see our clinical team.”

But patients tell a different story.

One source told me this week that she just learned her doctor of a quarter century had decided to flee Optum.

“When I spoke with her nurse she said hers is also leaving,” the source stated. “It’s getting worse not better. I fear soon we will all be displaced and unable to secure new doctors as many are now overloaded and not taking new patients.”

The area resident stressed how she worries that local patients will be forced to rely increasingly on urgent care, a service many people are already turning to with more regularity.

“It seems like someone needs to start a class action suit,” the source remarked on Monday.

Latest Document Haul/Back to Billing

In terms of billing in particular, Kleff has noticed discrepancies when comparing charges, payments, adjustments and balances. Numbers simply don’t square.

“And usually what I did in the past when the balance was $50, I just paid it because it would have taken me too much anxiety and time to figure it out in detail,” Kleff told me last week while studying a bill from the company.

He highlighted that while the discrepancies might seem minor for individual patients, when multiplied across the entire system the accumulated amount is substantial.

“A dollar here, a dollar there adds up to millions they put in their pocket,” said Kleff, an award-winning host and producer for German public radio covering politics and music before retirement.

In fact, speaking of the billing issues, the day I initially connected with Kleff last week just happened to coincide with the day I received 82 new pages of documents from the state Attorney General’s Office about CareMount/Optum, resulting from my January Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) request.

Although past pieces in this series dove deep into the billing issues, using prior records released by the AG’s office, the latest document haul establishes a wider pattern of behavior.

While all companies can legitimately face scattered billing issues, CareMount’s refusal to fix a problem that patients have been complaining about to varying degrees for decades speaks to the self-interest of allowing systemic overcharges to fester. (CareMount Medical, renamed as such in 2016, started in 1946 as Mount Kisco Medical Group, eventually referred to as MKMG; Optum came to town last year.)

In a Mar. 1, 2021, letter to CareMount’s billing director, included in the documents I obtained from the AG’s office, a patient of more than three decades outlined a discrepancy between a billed amount of $203.49 and the actual amount they owed, which was $86.52.

They provided a breakdown of recent visits and their respective charges.

The patient also mentioned being “harassed almost daily” by a collection agency, Immediate Credit Recovery (ICR), for a $163.49 debt that they insisted had already been paid.

“Should you have a manager in the Westchester area with whom I could meet, I would be happy to bring over the bills and other paperwork that show we no longer owe CareMount (via IC) that $163.49,” the patient wrote.

$6.52

The documents also detail a disturbing case from almost three years ago. On Jan. 26, 2021, a patient expressed frustration about being charged for the same provider visits across multiple bills, leading to confusion and the impression of owing more than they actually did.

The problem arose when the patient’s wife paid a recent invoice, but then a bill collector contacted them for a seemingly separate amount.

“Just because a provider visit appears on multiple statements, though, it does not mean we are supposed to pay for the visit multiple times,” the frustrated patient explained. “This is what I was unable to explain to the representative I reached in your department.”

The patient also provided detailed documentation, including spreadsheets and marked-up statements, to illustrate that many provider visits appeared on multiple bills but should not be paid for multiple times.

They requested CareMount update their records to reflect the correct obligation and cease bill collection efforts for the most recent billed provider visit, which amounted to $6.52.

That small amount actually speaks to the seriousness of the issue in the aggregate. It’s much easier for patients to detect, and much more worthwhile for patients to push back on large overcharges.

But whether through incompetence or something worse, a sizable company can more easily bolster its coffers with modest overcharges instead of big ones.

Good for this patient for being so eagle-eyed and diligent, standing on principle. But how many among us would notice or follow up about $6.52, let alone muster the energy to complain to the state Attorney General’s Office?

‘Phantom Past-Due Amounts’

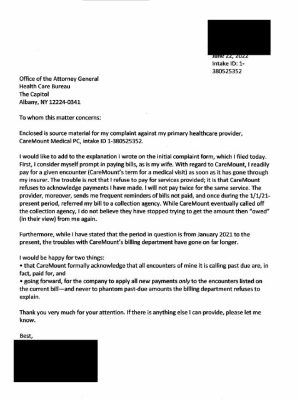

In a June 22, 2022 letter, a patient explained how they promptly pay for medical services once they are processed by their insurer but claimed that the healthcare operator often failed to acknowledge these payments.

“While I have stated that the period in question is from January 2021 to the present, the troubles with CareMount’s billing department have gone on far longer,” the patient wrote.

Insisting they “will not pay twice for the same service,” the patient also mentioned receiving frequent reminders and having their bill referred to a collection agency.

“I would be happy for two things,” the patient stated. “That CareMount formally acknowledge that all encounters of mine it is calling past due are, in fact, paid for, and going forward, for the company to apply all new payments only to the encounters listed on the current bill, and never to phantom past-due amounts the billing department refuses to explain.”

People are often inclined to just pay up and be done with it because the healthcare organization has embraced the contentious practice of sending collection agents after patients even when charges are credibly challenged.

For instance, in a July 13, 2021 letter, a patient expressed their concerns about receiving two consecutive bills from CareMount totaling $404.63.

They provided a check for $236.15, explaining that this was the amount they were paying due to the organization’s failure to adequately apply a previous payment to the relevant encounter.

Specifically, they mentioned a recent surgery for which they had paid $344.90. However, only $176.42 of that payment was applied to this particular bill, leaving $168.48 unaccounted for.

The patient mentioned that CareMount previously sent a collection agency after them for a similar amount, which was eventually recalled. They also said they remained worried that the organization might still claim they owe this amount, despite their previous explanations and payments.

“I cannot ascertain precisely where the other $168.48 went, but it was only a few months ago that CareMount sent a collection agency after me for the amount of $163.49, which is only $4.99 less than $168.48,” the patient wrote. “Granted, I had made a case for how I’d already paid the $163.49 (and more), and someone in your office must have believed me because the collection agency was called off. But given the most recent bills, I can only conclude that the imagined debt had never really gone away – and that CareMount continues to claim I owe it.”

‘Unprofessional’

Thankfully, some patients have been willing to point out how the billing issues are structural in nature, not just the result of occasional human error.

Take, for instance, a Sept. 27, 2021 letter where a patient complained about CareMount’s duplicative billing for services previously owed and paid.

They summarized their efforts to address outstanding encounters and the payments made, stressing that monthly bills should only reflect encounters for which payment is still owed.

The patient provided details regarding specific encounters and payments, detailing instances where they believed they’d overpaid.

“Applying payments intended for specific encounters to previous visits not listed on the current bill is nothing short of unprofessional,” the patient wrote. “This repeated practice on your part lies at the root of the problem.”

You have to wonder what the healthcare organization’s billing staff is told by management when reviewing such forcefully argued, evidence-based complaints.

Why must patients contact the state Attorney General’s Office to get clearly documented billing errors fixed?

With No Due Respect

Speaking of the AG’s office, one patient in particular didn’t pussyfoot around an implicit threat.

In a Jan. 26 letter last year, the patient voiced frustration with the billing department’s failure to seriously review their account.

“If you persist in billing me for the many prior encounters for which I have paid – and have reminded you about multiple times – my next communication will not be with CareMount,” the patient wrote. “It will be with the office of NY Attorney General Letitia James.”

The patient said James’ staff “will be very interested in knowing how a major medical facility attempts to wear down its clientele by repeatedly billing them for services paid for, even to the point of sending credit agencies to threaten them.”

“Trust me,” the patient added, “I have very good records.”

Spidey

As in the last batch of documents, there are also blacked out portions that would raise almost anyone’s Spidey senses.

Erin Signer, a Health Care Bureau Helpline Advocate at the state Attorney General’s Office, sent an Aug. 16 e-mail with attachments labeled as secure. But who Signer sent the documents to remains curiously obscured.

Although it’s reasonable to wonder whether the copy was simply blacked out to protect someone’s privacy, just three weeks later Signer referenced a seeming lack of cooperation on CareMount’s part.

In an e-mail from Sept. 6 2022, in a message marked with a label of “High” importance, Signer indicated that standard e-mail correspondence would not be a secure way for the medical group to communicate on the sensitive matter. (That’s not a warning Signer gave for other conversations.)

“I am writing to follow up on the inquiry I submitted by secure e-mail on June 23, 2022,” Signer wrote. “To date I do not have a record of receiving a response or update.”

Records officer and Assistant Attorney General Abisola Fatade advised me in a form e-mail last Tuesday that by Dec. 6 the office “will be able to produce to you the next installment of responsive records.”

‘That’s Fraud’

I also stumbled upon a local source last week who confirmed everyone’s worst suspicions.

Jan Greenbaum, the operator of the Brewster-based Greenbaum Insurance Services, LLC, represents more than 800 clients. She works with seniors enrolled in various Medicare supplement plans, each with its own set of terms and conditions.

Some of these plans feature annual deductibles, while others offer deductible-free coverage.

However, “In each scenario, Optum bills many of the patients the full cost of the visit,” Greenbaum told me.

Even after satisfying deductibles and copays, some clients are still being billed for medical services.

No other area healthcare provider has done the same in her experience.

“CareMount is the only one I have the problem with,” Greenbaum asserted in an interview last week while also listing the other local providers she works with on behalf of her clients.

Fear

Greenbaum said she doesn’t understand how the billing department can possibly go into a patient’s records, notice the patient has already been reimbursed by a Medicare supplement plan and then accept a payment in any plausible, acceptable way.

“Double billing is fraud, they are collecting payment from Medicare, the supplement insurance carrier and then receive payment from the patient,” Greenbaum said. “When the patient sends them payment and their billing department posts their payment, don’t they see they’ve been paid already by Medicare and the supplement carrier? I’m sure they do, but the payment is not sent back to the patient.”

She personally reaches out to CareMount/Optum to rectify double billing issues for her clients.

It’s already happened about half a dozen times this year, but those are just the clients that notice and are willing to deal with it.

“They get nervous, they think their credit is going to be ruined and they just pay it,” Greenbaum said, referring to the majority of her clients.

A senior herself at 74, Greenbaum also deals with billing issues personally as a patient. She used to provide documentation, offering her Medicare ID card and Medicare supplement card to resolve inaccurate charges.

“And then I finally said, ‘You know, the hell with it,’ and I just get rid of the bills,” she said. “I don’t even bother anymore.”

The ‘Better’ Old Days

While Greenbaum conceded at least the theoretical possibility that the ongoing issues are just the result of poor training, she also pointed out how this degree of ineptitude would normally compel a responsible company to make a change and fix a problem that’s unfairly burdening consumers.

“If they do not realize that they are double billing the patient, then the billing staff either needs to be trained better or needs to be replaced,” she said.

Amidst the billing issues, and other reporting on the medical-industrial complex, I happened to have a personal opportunity last week to learn more about the inner workings of our troubled healthcare system from firsthand sources during a minor medical procedure at Phelps Hospital.

A pair of Northwell clinicians spontaneously told me about their discontent with the institution’s incentive system of the past few years, an approach they described as myopic and exclusively oriented around financial motivations. (Northwell is New York’s largest health system employer, with about 85,000 people.)

The clinicians cited a shift to a metric-based system, expressed dissatisfaction with a departure from the community hospital atmosphere of the past and voiced concerns about protocol restrictions on medical decisions.

Additionally, one of them mentioned layoffs enacted just last week while also complaining about the purchase of cheaper supplies for patients over staff recommendations for superior care.

“It used to be so much better here,” she told me.

This Series

I’d previously planned to have this week’s column – part nine of a series – feature feedback from local elected officials about the documented problems vexing their constituents.

But given this new reporting, I wanted to publish these details first.

I’m pleased that our representatives will be able to review the additional revelations before commenting (and hopefully acting) on the latest particulars.

The next batch of digital documents from the AG’s office should be accessible to me in about three weeks.

Between a retired area doctor who contacted me this past weekend and a planned interview with a local congressman, there will be lots of ground to cover in this series between now and year’s end.

I’ll also eventually delve into the industry’s indefensible refusal, broadly speaking, to give a full-throated endorsement of established and evidence-backed Eastern methodologies, such as acupuncture, herbal medicine and mindfulness practices, both in healthcare treatment and insurance coverage.

Finding lawmakers bold enough to prioritize reform won’t come easy. In the 2022 election cycle, according to OpenSecrets.org, UnitedHealth, ranking 201 out of 31,955 contributors in the category, gave more than $3 million in political donations to candidates, parties, and committees, aiming to wield influence across party lines. There seems to be an enormous return on that investment.

For instance, Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-NY) was among United’s top recipients, receiving $166,895, while Sen. Mike Crapo (R-ID) secured $106,200—highlighting the significant impact of corporate interests and political maneuvering on shaping healthcare policy.

All Systems Not Go

Lastly, one quick ideological note: Rejecting the corporate medicine status quo while embracing healthy capitalism does not need to be a mutually exclusive affair.

Free markets are ideally designed to achieve positive outcomes for as many people as possible. But this free market isn’t free.

It’s a closed marketplace, occupied by powerful entities that distort fair competition and undermine the health of patients – Democrats and Republicans, liberals and conservatives.

While solutions are admittedly complicated and potentially divisive, achieving broad consensus on at least identifying the problems is far easier to imagine.

It’s a rare area where you could reasonably hope to see MSNBC liberals, Biden Democrats, Romney Republicans, and Fox News conservatives all in general alignment about the serious symptoms, if not the needed remedies.

Only a very select few – perhaps executives tucked away in boardrooms – are likely content with the front-end impact of the back-end infrastructure wiring our healthcare system.

Parting Shot

The physicians, by and large, at Optum and elsewhere, are deeply caring, elite professionals, seeking to do good, trapped inside a corporate vortex of rushed appointments and cookie cutter, malpractice-fearing diagnostics.

Who really wants doctors serving as de facto corporate account managers?

Accountability (beyond modest fines that are just viewed by CEOs as the cost of doing business) is needed, along with reform, to ensure genuine competition and better results.

As for Kleff, while he’d love to just relax and enjoy retirement, he said he’s now highly motivated to advocate on these issues.

“I feel kind of responsible, too, for the system,” he said when discussing his letters to Optum’s president along with his general persistence. “I’m concerned how the system works. So that’s why I don’t sit back and say let’s forgive.”

Stay tuned.

Adam Stone is the publisher of Examiner Media. Contact him with tips and feedback at astone@theexaminernews.com.

Corrections:

Sourcing & Methodology Statement:

References:

Adam has worked in the local news industry for the past two decades in Westchester County and the broader Hudson Valley. Read more from Adam’s author bio here.