Car Shortages Cause Headaches for Westchester Buyers

News Based on facts, either observed and verified directly by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.

COVID-created supply chain problems wreak havoc for local residents and dealers.

If you’re in the market for a new car right now, you’re likely going to have to make at least one compromise, perhaps a few.

For White Plains resident Robert Pepper, who recently bought a pre-owned red 2019 Honda Civic Si Coupe he had his heart set on, that compromise meant getting the car delivered from a New Jersey dealership 150 miles away to a nearby parking lot, teaching himself how to drive stick shift on the way home and paying a higher price.

Had Pepper bought his Civic Si in late 2018 or 2019, he would have spent the same amount on a brand-new vehicle as he did for the used one.

“I had been doing research, and there were a handful of YouTube videos and articles saying ‘look how expensive cars are right now’ and ‘don’t buy a used car now,’” Pepper said.

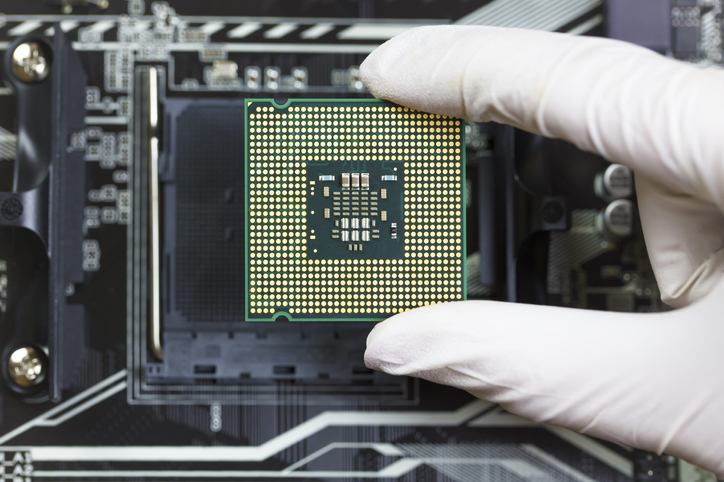

WHEN THE “CHIPS” ARE DOWN

A global shortage of semiconductors, the small but essential microelectronic chips and components that control many functions in modern vehicles, due to the pandemic — coupled with rising car ownership across the United States — are to blame for higher prices, increased demand and less supply of new and used vehicles.

Michael Ianelli, Owner of Toyota City in Mamaroneck and four other dealerships in the area, said they are certainly feeling the impact of the chip shortages.

“We’re down about 65 percent in inventories from where we’re supposed to be on the ground,” Ianelli said, noting that pre-shortage, Toyota City had about 200 cars on the ground, compared to the 70 to 80 they have now.

“[The shortage] is changing the way we do business,” Ianelli said. “We’re selling what’s incoming instead of selling what’s on the ground.” With increased demand and decreased inventory, Ianelli said increased gross profit is helping his dealerships cover their expenses.

“We’ve got a small premium that we put on every car, mostly around $1,000, some cars $2,000,” Ianelli said. While Ianelli refuses to gouge customers during this time of limited inventory, he shared that some dealerships are charging $10,000 to $20,000 more for vehicles.

When asked how quickly cars sell out once they arrive on the lot, dealers across Westchester County shared the same sentiment: it’s almost immediate. Some prospective buyers are putting money down before a car is even on the lot to ensure that they’ll get a vehicle when new shipments arrive. Other buyers are opting to custom-order their vehicles, which the manufacturer will then schedule to be built based on the fact that they are already sold.

RIPPLE EFFECTS

The car shortage is causing ripple effects in related markets and industries. In some cases, used car sellers or online auto traders are buying out individuals’ leases to gain access to more vehicles. Some dealerships are countering this trend by requiring that leased cars be returned to the dealership from which they were leased. Rental car companies are also scrambling to get enough cars, with many turning to auctions. “There’s a tremendous demand for pre-owned [vehicles],” Ianelli said. “With this national shortage, the manufacturers aren’t selling to the rental car companies like Hertz, Avis, and Enterprise.

“They’re not getting new vehicles, so they’re at the auction buying everything they can turn around and register and rent,” Ianelli continued, highlighting that rental cars are also pricier and less available these days.

For used car dealers, chip shortages and the resulting lack of new-car inventory are making the demand for used vehicles continue to surge — a trend that emerged as more people avoided mass transportation due to the pandemic.

“Whatever we get in is selling within days, sometimes within minutes.” Westchester Auto Exchange owner Jason Khoury

“The used cars are just flying off the shelves,” Jason Khoury, owner of Westchester Auto Exchange, said. “Whatever we get in is selling within days, sometimes within minutes,” Khoury said. “And the newer used cars that we’re getting in from 2020 or 2021, people are paying over sticker from what they were when they were new.”

Bedford Hills resident Asher Stockler, who recently purchased a used 2018 Acura TLX from Curry Acura in Scarsdale, said overall he got lucky with his experience, despite the shortages. When he initially went to Curry Acura, they didn’t have a car that met his desired specifications and price point. But because he was not in immediate need of a new vehicle, he was able to wait it out.

“I hung on for a few weeks and would text the dealer on and off, asking ‘did anything come in yet?’” Stockler said. “And [the dealer] said basically they don’t know what kind of inventory they’ll get.”

“It is all up in the air week-to-week what they’re able to get, so we just had to play it by ear.”

After a few weeks, Stockler’s patience paid off, and a 2018 model with all-wheel drive came in.

“If I needed a car immediately, I would have had to pay more for whatever inventory they had,” Stockler said. “I would have had to adjust my purchase upward.”

WEAK LINKS IN THE SUPPLY CHAIN

Nimish Adhia, an Associate Professor of Economics at Manhattanville College, highlighted that the pandemic exposed vulnerabilities to global supply chains, not just for automakers but for industries at large.

Over the past few decades, many companies have moved to just-in-time manufacturing, which is more efficient because it reduces the need to hold inventory of supplies and parts. However, it is less resilient to disruption, Adhia noted, because the process comes to a screeching halt if one key component fails to arrive in time. In the automaker’s case, it’s the semiconductor.

“In the pre-pandemic era, the lack of resiliency was not an issue because transportation and trade barriers to the movement of supplies were only falling and the parts kept arriving on time,” Adhia said. But the pandemic suddenly reversed this trend, making disruptions more frequent and the lack of resiliency more apparent.

“It has become most salient in the automobile industry because the demand for automobiles has surged in a way that defied the expectations of the automakers early in the pandemic,” said Adhia, who noted the pandemic has created a whiplash for the entire automotive industry.

“When the pandemic first hit, automobile companies expected a prolonged recession and a drop in demand for their products,” Adhia said. “So, they went ahead and canceled many of the orders with their suppliers, such as the chip-makers.

“The companies’ expectations were upended when many Americans began changing their lifestyles (moving to the suburbs, avoiding public transportation, et cetera) and began buying more automobiles,” Adhia continued. “The stimulus checks further greased the wheels of those heading for the car dealers’ lots.”

Because chips are customized and made to order for each manufacturer, it takes six months to a year for automobile companies to receive delivery for chips after the order has been placed. Some manufacturers have even resorted to selling vehicles without certain semiconductor-dependent features that they would normally come with, to reduce the demand for chips.

With an influx of orders for chips right now — not only from automakers but also makers of electronics and appliances — “the automotive industry finds itself at the back of the line in a slow-moving lane,” Adhia said.

With improvements in supply not expected until January 2022 at the earliest, car dealers will have to continue making do with the hand they’ve been dealt, and prospective buyers will have to keep waiting in a crowded queue.

Bailey Hosfelt is a full-time Reporter at Examiner Media, covering LGBTQ+ issues, climate change, the environment, and more. You can follow Bailey on Twitter at @baileyhosfelt.

Examiner Media – Keeping you informed with professionally-reported local news, features, and sports coverage.