Birding the Zombie Apocolypse; Owls in the Library

Opinion Advocates for ideas and draws conclusions based on the author/producer’s interpretation of facts and data.

By Brian Kluepfel

Twenty-nine brave souls gathered at the gates of Sleepy Hollow Cemetery last weekend for a bit of birding and graveyard touring. Our tour guide Christina reminded us that more than 47,000 souls are buried on this hillside Hudson overlook; there are only 10,000 living folks in the town.

“That means we’re in trouble when the Zombie Apocolypse strikes,” she joked.

Or was she joking?

Birders are known for facing the hardiest of challenges when trying to add to their life lists; but in this case, would it be more appropriate to call today’s tally a “death list?”

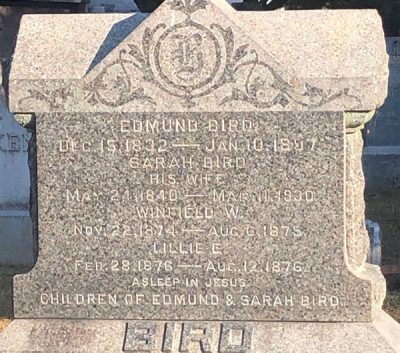

As we passed by the markers of various material – marble, granite and “white bronze” (zinc) – and size, ranging from hand-sized memorials to the two-bedroom Leona and Harry Helmsley mausoleum, we kept our wits about us, that’s for sure.

Saw Mill River Audubon Executive Director Anne Swaim led the birding portion of the two-hour walk, and her goal was simple – we’d try to spot more birds than we had people on the walk. Since our group comprised 29 persons, we had our work cut out for us.

Thanks to some perspicacious comrades, we did see a lot of avian wildlife. Most obvious were the garrulous groups of blue jays heading down the Hudson Valley to wintering grounds. More subtle was the yellow-rumped warbler sounding from behind the Rockefeller mausoleum.

A glimpse at Owen Jones’ gothic grave was interrupted by the cry “robin!” Local robins, we learn, are bigger and darker in the winter, likely migrants from the north as “ours” have taken to “terrorizing strawberry farmers in Florida.”

Chickadees and nuthatches made themselves known in the bowers of pine; a palm warbler, we discovered, has the worst name in birding (named by a scientist who saw them in Caribbean palm trees, it truly is a bird of the boreal forest). A massive group of starlings wove black-matrix-printer patterns back and forth between trees, perhaps alarmed by a Cooper’s hawk nearby or the pair of bald eagles turning like ocean gyres in the sunny autumn skies.

Some walkers noted the remarkable variety of trees and plant life. Sleepy Hollow Cemetery is a Level 1 arboretum and has officially marked 28 different tree species. (There is a particularly gnarled and menacing one next to Washington Irving’s plot.) The Riverview Natural Burial overlooks the Pocantico River, providing a great spot for birds, wildflowers and migrating monarch butterflies, too. A purple lilac bloomed, fooled by the weather; further up the trail, a northern mockingbird poked its head above a tree crown replete with red berries.

We were subtly reminded that boxwood shrubs smell like cat pee, the olfactory reminder forever ruining the plant for our more sensitive walkers.

After two hours, we returned to the creaking gates of Halloween-mad Sleepy Hollow, and put our collective heads together for a final tally: 30 birds! We surpassed the number of hikers. Challenging the ghosts of Sleepy Hollow was worth it, after all.

Sunday at the Ossining Library provided a close-up view of raptors with Orange County wildlife rehabilitator Laura Jaworski. Three owls and one kestrel later, the 50-plus attendees all had an increased knowledge of these birds of prey, and most deftly avoided the bird poop near the front row of the auditorium.

First up was Lazarus, a seven-year-old Eurasian eagle owl who was bred in Goshen. This species – the famed “Flaco” of Central Park was also a Eurasian eagle owl – has startling orange eyes, and though seemingly massive, weighs only about four or five pounds. For an idea of scale, if our eyes were the same relative scale to our heads as Lazarus’s, they’d be the size of cantaloupes.

Owls have zygodactyl feet, meaning two toes point forward and two backward, making it easier for them to hold onto prey. (Ospreys, woodpeckers and parrots also have this foot structure.) While eagle owls can exert 500 pounds per inch of pressure with their talons, humans can only muster 50. They have 14 cervical vertebrae; we have seven.

Next up was a spectacled owl, who roam the lowland forests of Central and South America. The huge brown circular patterns around their eyes give them their name, but their striking yellow eyes – the same color as a short-eared owl – may give scientists a clue to their behavior. It’s thought that perhaps orange-eyed owls are crepuscular (dusk and dawn) hunters; the yellow eyes of the spectacled owl mark a diurnal (daytime) hunter.

The dark eyes of the barn owl indicate a nighttime hunter. This barn owl was a dark morph; a great variety in shading occurs in the species throughout their range. Poisoning currently is a big problem for this owl, which thrives on rodents that we humans often try to eliminate with dangerous amounts of rodenticide.

Last to appear on stage was an American kestrel named Winston. Jaworski noted that these blue jay-sized hunters, our smallest North American falcon known for hovering over fields, have to take good care. Coopers hawks will eat them. They can easily be both predator and prey! She paid the small fellow tribute as “a huge personality in a little frame,” and Winston got a lot of post-show love; the advantage of going on last.

From the dark shadows of the cemetery to the bright lights of the library, Saw Mill River Audubon gave local birders much food for thought.

Brian Kluepfel is a member of Saw Mill River Audubon and encourages you to join in their activities. You can find him online at briankluepfel.com.

Examiner Media – Keeping you informed with professionally-reported local news, features, and sports coverage.