Anthony Doerr Shines ‘Light’ on Unforgettable Duo

Review An assessment or critique of a service, product, or creative endeavor such as art, literature or a performance.

By Michael Malone

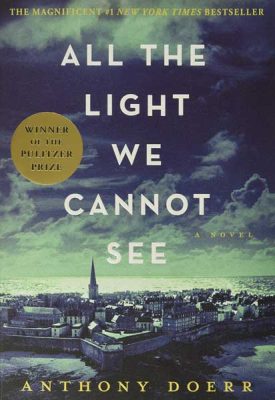

“All the Light We Cannot See,” from Anthony Doerr, is a big, bold, terrific novel about a blind French girl and a sensitive German boy and how their lives come together as World War II spreads across Europe. The characters, Marie-Laure and Werner, get alternating chapters.

“All the Light We Cannot See,” from Anthony Doerr, is a big, bold, terrific novel about a blind French girl and a sensitive German boy and how their lives come together as World War II spreads across Europe. The characters, Marie-Laure and Werner, get alternating chapters.

The girl goes blind at age 6, and her father, who is a locksmith at the Museum of Natural History in Paris, builds her a perfect miniature replica of their neighborhood so she can memorize it by touch.

When she is 12, the Nazis invade Paris, and Marie-Laure and her dad split for her uncle’s place in Saint-Malo. They bring the museum’s most valuable jewel.

Over in Germany, orphan Werner can fix radios at a young age, which gets him a place in Hitler Youth. Tracking the Nazis’ resistance, he ends up in the walled city of Saint-Malo, and meets Marie-Laure.

The book came out in 2014 and the Netflix series launched two weeks ago. There are four hour-long episodes – Aria Mia Loberti plays the French girl and Louis Hoffman portrays the German boy. Mark Rufalo is Marie-Laure’s dad.

“All the Light We Cannot See” won the Pulitzer Prize in 2015. Not many novelists can claim a Pulitzer. This year, Barbara Kingsolver got one for “Demon Copperhead” and Hernan Diaz for “Trust.” Louise Erdrich was given one for “The Night Watchman” in 2021. Colson Whitehead got a Pulitzer for “The Nickel Boys” in 2020, and for “The Underground Railroad” back in 2017.

The Pulitzer is sky-high praise to say the least.

Does ‘All the Light’ deserve it? In fact, it does. Doerr tells his tale with abundant aplomb, deftly balancing his mounds of research with skillful storytelling. You don’t really think about how much work went into the novel. You just enjoy reading it. You see the world slightly differently from having read it. You learn from it.

You learn about World War II, and what it was like to be a child in the war. You learn about blindness. You even learn about radio technology.

Doerr writes early on, “Marie-Laure LeBlanc stands alone in her bedroom, smelling a leaflet she cannot read. Sirens wail. She closes the shutters and relatches the window. Every second the airplanes draw closer; every second is a second lost. She should be rushing downstairs. She should be making for the corner of the kitchen where a little trapdoor opens into a cellar full of dust and mouse-chewed rugs and ancient trunks long unopened.

“Instead, she returns to the table at the foot of the bed and kneels beside the model of the city.”

The book is a hefty 530 pages, but it moves quickly, thanks to chapters that run two to three pages. Doerr told Powell’s Books, a noted independent bookseller, “It’s like I’m saying to the reader, ‘I know this is going to be more lyrical than maybe 70 percent of American readers want to see, but here’s a bunch of white space for you to recover from that lyricism.’”

Readers lapped it up. ‘All the Light’ has a glittering 4.32 rating, out of 5, on GoodReads, with some 1.5 million people rating. Janet Maslin wrote in The New York Times, “Boy meets girl in Anthony Doerr’s hauntingly beautiful new book, but the circumstances are as elegantly circuitous as they can be.”

Kirkus Reviews said, “Doerr captures the sights and sounds of wartime and focuses, refreshingly, on the innate goodness of his major characters.”

Doerr offers this peek at Werner and his innate goodness, in the orphanage, early in the story. “He is undersized and his ears stick out and he speaks with a high, sweet voice; the whiteness of his hair stops people in their tracks. Snowy, milky, chalky. A color that is the absence of color. Every morning he ties his shoes, packs newspapers inside his coat as insulation against the cold, and begins interrogating the world. He captures snowflakes, tadpoles, hibernating frogs; he coaxes bread from bakers with none to sell; he regularly appears in the kitchen with fresh milk for the babies. He makes things too: paper boxes, crude biplanes, toy boats with working rudders.”

I’d never heard of Anthony Doerr before reading the book. My friend Gertrude had brought it to me when I was stuck in the hospital. Doerr’s most recent novel is called “Cloud Cuckoo Land.” He wrote another called “About Grace,” a memoir called “Four Seasons in Rome” and the short story collection “Memory Wall.” He won a Guggenheim Fellowship. From Cleveland, he lives in Boise. He’s 50.

The man can write. Put a bit more eloquently, by Vanity Fair, Doerr “takes language beyond mortal limits.”

Reviews of the Netflix series were so-so. Reviews of the book were remarkable.

Read the book.

Journalist Michael Malone lives in Hawthorne with his wife and two children.

Examiner Media – Keeping you informed with professionally-reported local news, features, and sports coverage.