After Indian Point

News Based on facts, either observed and verified directly by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.

A community in economic and environmental transition as decommissioning begins

Good morning! Today is Wednesday, December 29, and you are reading today’s section of Examiner+, a digital newsmagazine serving Westchester, Putnam, and the surrounding Hudson Valley.

Today’s Examiner+ is sponsored by Greca Mediterranean Kitchen+ Bar in White Plains.

For nearly six decades, Buchanan residents lived with a nuclear power plant operating in their backyard. Indian Point, which generated approximately 25 percent of the Lower Hudson Valley and New York City’s annual electricity consumption, powered off its last remaining nuclear reactor last April.

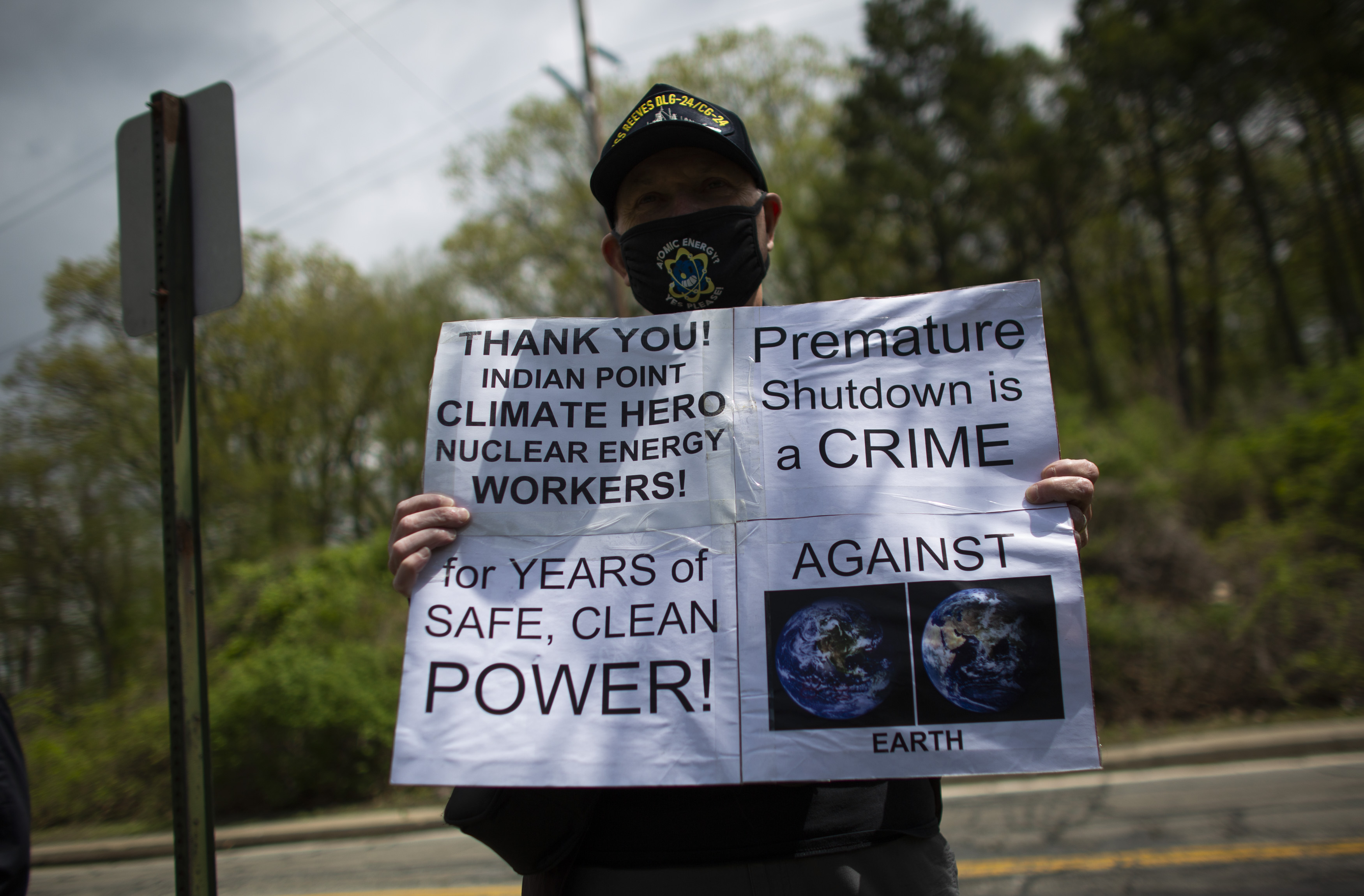

The decision, despite being four years in the making, was described as a dark day for the community. While environmental activists saw the plant’s closure as the culmination of 50-plus years of mounting pressure, others viewed it as a short-sighted, even reckless decision.

Now, as Holtec — the New Jersey-based company that bought the plant from Entergy — oversees the decommissioning process, Buchanan, Cortlandt, and the surrounding area are left in a period of financial transition.

As the largest employer in Buchanan and Cortlandt, Indian Point not only provided 1,000 jobs at its peak but also gave millions in revenue to the local community.

Buchanan stands to lose 47 percent ($3.5 million) of its annual operating budget, while the Hendrick Hudson School District will lose $24 million annually. Cortlandt is estimated to lose $800,000, according to Town Supervisor Linda Puglisi. The Verplank Fire District is also estimated to lose $372,703, 64 percent of its annual budget.

“We had an agreement with Entergy that we will live here with the risk of a nuclear power plant in exchange for lower taxes,” says Joseph Hochreiter, Superintendent of the Hendrick Hudson School District. “One of the hardest things to acknowledge was that when the plant stopped making nuclear power, and therefore it wasn’t as great of a risk, the other end of the deal had to go with it.”

Until last year, Indian Point provided 30 percent of the school district’s total annual budget. Hochreiter says the district has had to raise its taxes and reduce expenses to counteract the financial impact Indian Point’s closure will have on the district.

“When the school district looks at reducing expenses, it’s usually two things: you reduce programs, meaning opportunities for kids, or you reduce the number of people you staff,” Hochreiter says. “Those are really emotional and tough conversations to have.”

Starting this September, the district is reorganizing its elementary students, which will save anywhere between $1.5 and $2 million annually.

“A direct result of Indian Point closing is that we had to make some very significant and important changes to where students go to school so we could save money,” Hochreiter says.

For eight years in a row, the district’s average tax increase was 1.04 percent — rising less than the cost of living. In the last two years, the increase averaged 5.5.

A lot of people were surprised when they realized the enormity of the financial impact Indian Point’s closure would have, Hochreiter underscores, especially because residents were used to paying lower taxes compared to Lakeland Central, Hendrick Hudson’s neighboring school district.

“As long as [Indian Point] was open, we accepted the risk in exchange for low taxes,” Hochreiter says. “That’s been the biggest hurdle and toughest conversation we’ve had with our community.”

While the blow to the district is significant, Hochreiter highlights that it won’t go from 30 percent to zero overnight. The district is receiving earmarked dollars through a state cessation fund, which will provide a percentage of lost revenue over the next seven years.

The supplemental income from the state, Hochreiter explains, will help soften the landing as the district works to readjust.

Jill Davis, Director of the Hendrick Hudson Free Library, says, like the school district, the library has experienced notable revenue loss since Indian Point’s scheduled closures began. Sixteen percent of its 2021 to 2022 budget, about $270,000, came from Indian Point’s PILOT (Payments in Lieu of Taxes) agreement.

If an agreement is not reached with Holtec, Davis says, they will have to make up the difference.

“Having known that this decrease was coming, the library board has been discussing how to best continue to provide excellent library services with the least financial impact on our community,” Davis says. “The board is optimistic that with just small increases to the tax levy each of the next five years, along with not increasing budgeted expenses, we can maintain a balanced budget.”

Because the library is an autonomous legal entity but not a taxing authority, it is not on its own eligible for cessation funds. However, the school district can apply on its behalf.

Davis says she is confident that the school district, which has always supported the library and included its interests when past PILOT money was available, will continue to do so with cessation funds.

The Village of Buchanan received its first cessation payment of $773,568 on October 26.

Today’s supporting sponsors are the Town of Yorktown…

…and the Peekskill Business Improvement District.

Employment Repercussions

William Smith, vice president of Utility Workers Union of America Local 1-2 (UWUA 1-2), who worked at Indian Point in the 1980s and 90s, says there were approximately 400 UWUA 1-2 members working at Indian Point prior to its closure. Now, 80 members are left working on the decommissioning phase, but the majority of previously steady plant employees lost their jobs.

“With our members [working], it’s probably only going to be another 18 months or so,” Smith says. “Those members will eventually also be looking for jobs.”

Smith says UWUA 1-2 is for clean, renewable energy but feels that the infrastructure has not yet been put into place to replace Indian Point’s energy output. “Since Indian Point was a clean running plant, they should have kept it open for another five to 10 years,” Smith says. “They were good, union-paying jobs.”

Thomas Carey, President of the Westchester-Putnam Counties AFL-CIO Central Labor Body, whose family worked at Indian Point for four generations “from construction right up to the closure,” says it’s crucial to use local labor for decommissioning. “It’s been a slap in the face for this community to shut down the plant with such short notice,” Carey says. “We have a skilled workforce, we have the people who kept the plant up and running, and these are the same people that should be disassembling it.”

Right now, Carey notes, his local is seeing a 15 to 20 percent unemployment rate as a result of Indian Point’s closure. “These jobs would be imperative for the local workforce,” Carey says.

Since Holtec took over Indian Point, Patrick O’Brien, senior manager of government affairs and communications at Holtec-operated Comprehensive Decommissioning International, says transitioning the workforce to the Holtec family of companies has been a top priority.

Due to the average age of the workforce, O’Brien says, many people decided to retire when Indian Point closed. Others who wanted to stay in the nuclear industry were offered positions to work on plants Entergy operated in the south. Some took jobs for utility companies like Con Edison.

Around 300 employees were able to keep their jobs and are now working on decommissioning the plant, which is in its very early stages of an estimated 12- to-15-year timeline to completely decommission the facility.

Both Unit 2 and Unit 3 reactors at Indian Point are de-fueled, O’Brien explains, and the spent fuel has been moved to the spent fuel pool. From there, the spent fuel will be moved into dry cast storage — a process that should be completed by 2024. Once spent fuel is in dry cast storage, 98 to 99 percent of its radiological contamination properties are taken away. In parallel, reactive segmentation work will occur first at Unit 3 then Unit 2 alongside waste extraction.

But where the spent fuel from Indian Point will ultimately go, O’Brien explains, is an outstanding question. While the Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982 was supposed to come up with a comprehensive plan to dispose of radioactive waste throughout the country, there is currently no federal repository.

There have been starts and stops on the federal level, O’Brien says, but ultimately no consensus has been reached.

“It’s not just an Indian Point issue, it’s an industry-wide issue,” O’Brien says. “Every reactor that’s operated in the U.S. still has the spent fuel on-site.”

A Power Vacuum?

While supporters of nuclear energy campaigned to keep the plant operating, others like nonprofit environmental organization Riverkeeper fought for its closure for over five decades, framing the plant as a continued safety risk and an ecological threat.

“I think people think about nuclear power in the abstract, but it’s important to remember that Indian Point was not an abstraction,” Richard Webster, lead program director at Riverkeeper, says. “Indian Point was a 60-year-old nuclear plant in a very poor location with a huge number of people within 50 miles. Because of that, the area was uniquely difficult to evacuate.”

The safety risks and adverse impact on the environment, Webster says, coupled with the rising costs of operating an aging nuclear power plant as the costs of renewables continued falling, all led to Indian Point’s eventual demise.

“The question wasn’t ‘Is Indian Point going to close?’,” Webster underscores. “The question was ‘When is Indian Point going to close?’”

While Webster says he and his Riverkeeper colleagues were extremely happy to see Indian Point close, it marks a transition period.

Prior to Indian Point’s closure, the New York Independent System Operator (NYISO) — which helps conduct comprehensive long-term planning for the state’s electric power system — ran a deactivation assessment, which found that, without Indian Point, energy reliability criteria would still be met.

However, at the time, three major generation facilities were under construction — a hydroelectric power plant in New Jersey and two natural-gas-fueled power plants in Orange County and Dutchess County. When NYISO also ran a scenario assessment without the three new generation facilities, it found that additional replacement sources of power would be necessary to maintain reliability following Indian Point’s deactivation.

In NYISO’s 2020 analysis of downstate energy capacity during the summer (when Indian Point Unit 3 was still running), 18 percent of 25,127 total megawatts came from nuclear power and 89 percent from fossil fuels. In 2021, with no nuclear power due to Indian Point’s complete closure, 93 percent of 24,188 total megawatts were generated from fossil fuels.

“[Natural gas use] will go up as a little bit as a result of Indian Point’s closure, but it will rapidly come down again as renewables, big connectors from upstate, and offshore wind kicks in,” Webster says. “There’s a short-term transition, but it really is very short-term.”

The state has also been forthright in this regard, sharing Webster’s sentiment that while there will be a short-term uptick in fossil fuel use and CO2 emissions, it’s expected to swing the other way as additional renewables come online in the near future.

But proponents of nuclear energy who wanted the plant to keep operating contend that this short-term increase in greenhouse gas emissions is too big a price to pay — especially when the state is struggling to follow through on its ambitious climate goals.

“In New York, particularly under the Cuomo administration, it grew in terms of gas, gas, gas all the time,” Herschel Specter, a nuclear engineer and member of the group Nuclear New York, says.

Specter, who was a federal regulator in the 1970s with the Atomic Energy Commission, says he would have liked to see Indian Point continue to provide carbon-free nuclear power at least through 2024, if not another 10 to 20 years.

As a regulator, Specter was responsible for ensuring Indian Point 3 was safe enough to be licensed. After the disaster at the Three Mile Island plant in Pennslyvania, Herschel was asked by the New York Power Authority, which owned the plant at the time, to defend Indian Point’s safety at a series of public hearings.

Now with the former governor no longer in office, Specter says the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) is beginning to course correct, shutting down applications for new gas plants and the amount of gas permitted to be burned at existing sites.

“I applaud that finally the NYSDEC has taken these actions, and, from an environmental point of view, they’re exactly correct,” Specter says. “However, what about the NYISO piece, which says we need to be reliable? I see a storm brewing in the future where NYISO says I can’t operate without these gas plants because Indian Point is gone, and now we have a tremendous conflict to resolve.”

Bailey Hosfelt is a full-time reporter at Examiner Media, with a special interest in LGBTQ+ issues and the environment. Originally from Connecticut and raised in West Virginia, the maternal side of their family has roots in Rye. Prior to Examiner, Bailey contributed to City Limits, where they wrote about healthcare and climate change. Bailey graduated from Fordham University with a bachelor’s in journalism and currently resides in Brooklyn with their girlfriend and two cats, Lieutenant Governor and Hilma. When they’re not reporting, Bailey can be found picking up free books off the street, shooting film photography, and scouring neighborhood thrift stores for the next best find. You can follow Bailey on Twitter at @baileyhosfelt.

We hope you’ve enjoyed today’s section of Examiner+. What did you think? We love honest feedback. Tell us: examinerplus@theexaminernews.com

Examiner Media – Keeping you informed with professionally-reported local news, features, and sports coverage.