The Moral of This Elephant Story: Love Trumps Hate

Opinion Advocates for ideas and draws conclusions based on the author/producer’s interpretation of facts and data.

By Adam Stone

In a time of political instability and national unrest, I wanted to share a powerful, almost magical animal story with you all, despite my recent hiatus from weekly reporting and writing.

I hope it provides ample justification for long-term optimism about humanity, even while acknowledging all the worldwide threats.

And unlike one of Aesop’s Fables, let me spoil the moral lesson right here at the top: a brighter future depends on us expanding our consciousness and our hearts and learning the true power of love.

Just a few months ago, while relaxing at home with my family one spring evening, an admittedly random, intuitive thought jumped to mind, seemingly out of nowhere: elephants are far more emotional than I’d ever considered, allowing for potentially deep interspecies connections.

To be clear, I’m not an animal expert by any stretch – unless parenting a pair of quirky dogs counts for credentials – and the wonders of wildlife isn’t really a topic I’ve historically thought much about in any meaningful way. (I’ve certainly never studied elephants, unless you count some Babar books from childhood.)

Granted, it’s common knowledge that elephants boast deep intelligence, marked by remarkable recall. Hence the expression “memory like an elephant.”

But this specific sense around the potential for a rich connection between a wild elephant and an empathetic person rushed into my mind inexplicably for some reason on that May evening.

Angry Herd

Intrigued by the emotional depth of elephants, I quickly found an incredible tale online that corroborated what I was feeling – the story of Lawrence Anthony, a South African wildlife conservationist and former businessman.

Anthony, a strapping bear of a man at 6-foot-3 with a charismatic presence, emphasized the emotional and social needs of animals in his work.

In 1999, he founded the Thula Thula Private Game Reserve in Zululand, South Africa, a lodge and animal haven where species like zebras and leopards can roam freely.

His approach focused not just on the physical but also the emotional rehabilitation of animals, recognizing their capacity for profound emotional connections.

That year, in 1999, he took on what some observers believed would be an essentially impossible rescue case – a culled herd of wild, aggressive, angry elephants – a group of nine beasts that animal control authorities and independent hunters were eager and poised to kill.

The elephant herd’s history was checkered with trauma, having witnessed the culling of their family by humans.

Their ancestral mistrust of people ran wide and deep.

Although Anthony possessed little formal knowledge about elephants at the time, he relied on his instincts to forge a relationship with the unruly, violent group.

Benign Presence

Elephants are a matriarchal society, and, as a result, Anthony focused considerable effort on building a rapport and establishing trust with the leader of the herd, Nana. (While that name was obviously assigned by a human, emerging scientific research suggests that elephants give each other what amounts to names, trumpeting unique sounds to distinguish between one another. That advanced level of communication and connection shouldn’t be surprising from a species known to cover their dead with leaves and dirt, showing signs of mourning in the burial process.)

In one broadcast, Anthony discusses how he tried to bond with the unpleasant elephant crew – a breeding herd that eventually grew to 21.

“I sing,” Anthony explained with a wise smile. “And they get used to the presence and they see that the presence is benign.”

But success didn’t come quickly or easily. Anthony and his colleagues initially made little progress, and the wild animals grew increasingly agitated; time appeared to be running out to keep them safe from slaughter.

He then decided to spend all his time with the elephants, who were kept within a fenced area. As he fed them daily, he tried to build a relationship, camping out with them 24/7, almost getting trampled in the process.

He was desperate to prove he came in peace.

‘Everything Just Changed’

One morning, following a particularly vexing three-week period with the embittered elephants, there was a momentous breakthrough.

Nana appeared to finally conclude that Anthony could be trusted. She approached him dramatically, in a made-for-TV moment, as the rest of the elephants looked on at her for guidance.

“Lawrence stood there and she put her trunk over the fence and touched him on the head,” David Bozas, one of Anthony’s colleagues at Tula Tula, recounted in a broadcast.

“It was at that moment everything just changed,” added Bozas, who had accompanied Anthony on the lengthy campout. “There was a serenity, it was calm, and he said, ‘Right, it is time to let them out.’”

Nana seemed to decide her family was now home, and the humans could finally be trusted.

The elephants had achieved transformative personal growth, becoming peaceful and warm, with a little help from their nurturing human therapist friend.

Anthony later earned international acclaim for his 2009 book, “The Elephant Whisperer,” where he details his experience of saving the herd of wild, rogue elephants on the brink of being killed.

But the most mind-blowing part of this story is yet to come.

Grieving Ceremony

Anthony died of a heart attack at the age of 61, on March 2, 2012.

His wife, an elegant French woman named Françoise Malby-Anthony, was despondent about the loss, grieving at home with other mourners two days after her husband’s death.

Then she looked out the window and couldn’t believe her eyes. The elephants had walked for about 12 hours, across several miles, to visit the Anthony home and pay their respects. (Elephants, using low-frequency sounds that can travel for miles, communicate with each other through vibrations felt in their toenails).

A total of 21 elephants, led by Nana, performed a ceremony in an organized procession, looking and sounding unambiguously grief stricken.

“Nana gazed at me,” Malby-Anthony wrote in recalling the experience in an article for the publication Guideposts. “So did the rest. As if they were waiting for something. Or someone. They remained like that for more than an hour, then marched up and down along the fence, rumbling. The same noise they’d always used to ‘talk’ with Lawrence. They seemed edgy. Distressed. Finally, they lined up one by one and made their solemn procession back into the bush.”

But I actually still haven’t gotten to the part that truly floored me.

Annual Tradition

A year after Anthony’s death, again on March 4, the elephants astonishingly returned to the home of their late friend, to pay tribute on the anniversary of the prior year’s inaugural ritual.

The procession was again led by Nana.

Yet the tradition didn’t end there.

“The year after that, again on March 4, they were back,” Malby-Anthony explained. “And again on March 4 the following year. They mourned him like one of their herd.”

These annual visits (reported to happen for at least seven years) showcase not only the elephant capacity for memory but also a deep sense of mourning and respect, behaviors that are strikingly similar to human rituals of remembrance.

Elephants are known for their strong family bonds and social structures. Living in matriarchal herds led by the oldest female, they form close-knit groups where relationships are crucial.

Malby-Anthony’s first book, “An Elephant in My Kitchen: What the Herd Taught Me About Love, Courage and Survival,” became an international bestseller. After her husband died, she took over operation of the reserve.

More recently she published “The Elephants of Thula Thula.”

“Some things in this world,” Malby-Anthony concluded in her Guideposts article, “are beyond human understanding – cannot be explained by reason, cannot be seen.”

Common Ground

Us humans are often inclined to think of ourselves as superior.

But there’s greater comfort in knowing how deeply aligned and connected we are with all living things. I recently noticed one of my dogs becoming slightly less anxious as I’ve given her more love and attention.

We do play a unique role here on our shared planet. Because humans were blessed with nimble thumbs, we’ve been able to build sophisticated tools and harness resources – from fire to electricity to artificial intelligence – that have allowed us to evolve societally in a way that is certainly specific to us.

Yet whether it’s whales, monkeys, octopuses, cats or dogs, we’re not alone in experiencing complex behaviors and emotions, even if non-humans lack the dexterous hands to develop advanced technologies.

Understanding the nature of intelligence in other living things offers all of us a gateway to more enlightened existence and a glimpse at the miracles of inter-animal communication.

And if we learn a big lesson from Anthony and Nana, our species can continue to evolve for the better, and transcend some of the recent darkness, to display strength, stoicism and courage in this unfolding drama.

Yes, there are stark, fundamental differences among us people, in terms of values. But there are also commonalities that can and should still bind us.

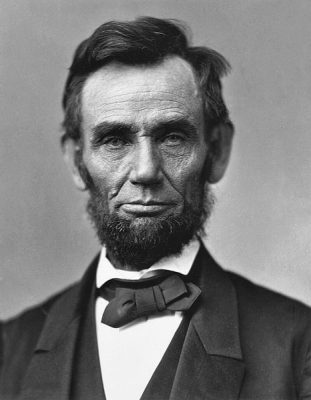

Lincoln’s Lesson

Consider a related lesson from Abraham Lincoln: hate slavery, not the slaveholder.

“I destroy my enemies when I make them my friends,” Lincoln was quoted as saying, apocryphal or not.

Finding and maintaining friendship with an ideological opposite is nothing compared to locking eyes with an angry, wild elephant and forging a connection.

This isn’t about naive hopes for Kumbaya in a nation divided over genuine, gaping cultural differences in this election season.

But it is about the very realistic possibility of treating each other with more kindness on an interpersonal level, neighbor-to-neighbor, and watching that goodness go viral in our local worlds.

Do I always perfectly practice what I preach? Of course not. Part of this writing is an admonishment and reminder to myself.

It starts with each one of us, and can spread throughout neighborhoods and towns like a stone rippling through a pond.

We can embrace our human tribes without pledging allegiance to their worst tendencies.

Our desire for connection can sometimes lead us astray, propelling us to parrot venom, pushing us away from our better angels.

Parting Thoughts

Hate has undoubtedly metastasized like a cancer inside our body politic.

But doubling down on civil conversation, leading with kindness and compassion, remains the cure, even if it seems impossible in one scenario or another.

It’s something you can do and control today.

We’re here in this human body for less than a blink of a historical eye. The least we can do is be the change we want for the world in our personal interactions.

Every great religion and philosophical tradition preaches at their core, at their best, that treating each other with more kindness and understanding can produce healthier coexistence.

If a traumatized, hostile elephant and a passionate, empathetic human can forge an unbreakable bond, imagine the possibilities for all of us.

Share this message – this elephant/human story – with the person or people in your world who need it most.

Love can trump hate.

Keep the hope, and pass it on.

Adam Stone is the publisher of Examiner Media. Email feedback to astone@theexaminernews.com.

Adam has worked in the local news industry for the past two decades in Westchester County and the broader Hudson Valley. Read more from Adam’s author bio here.